Squishy, vivid, frozen, frothy – architect and artist Antonio Torres’s wildly colorful and whimsical built spaces are often created using membranes filled with gases, liquids and organic materials, inviting people to crawl in, jump, touch and play.

Here, we ask him about his incredible works and where his inspiration comes from.

Tell me about yourself and how you became an artist – because, as I understand, you were originally trained as an architect.

Actually, the first time that anyone called me an artist was the TED Fellows team! I have always considered myself an architect, but after graduate school, my work became more multidisciplinary, bringing aspects of art into architecture and playing with it. So this is new for me.

Do you object?

No, not at all. I think it’s good when somebody describes you as an artist and you don’t have to call yourself one.

But I always knew I wanted to build things. It has been part of my life for a very long time. Most of my family is in construction and landscaping, so everyone has a pretty natural grasp of materials and how to put things together. I don’t know if that’s what got me involved in architecture, but it definitely is something that plays out right now. I was always around job sites, from when I was 13. At some point I was even thinking of doing civil engineering. That road would have probably been a big mistake! Now I’m trying to explore new architectural possibilities in unifying art, sculpture, soft and living materials and hilarious forms in the hope of finding different building blocks in architecture. I think I have a pretty good grasp of how to put traditional methods together – now it’s about trying to challenge what it means to build.

I grew up in a small village in the state of Michoacan until I was 12, and then my family moved to Chicago. That’s where I did my undergrad, at the University of Illinois at Chicago. In my last year, I had the chance to study at the School of Architecture in Verailles, France – a pivotal moment for me. When I came back, I ended up doing a three-year master’s degree in architecture at UCLA, where I met my partner in crime, Michael Loverich, with whom I founded The Bittertang Farm, our design studio. Now I am back in Mexico and it has been very receptive to me and my work.

“Ice caves of the Polar Regions are a rare treat to those who travel there. Created by hundreds of years of accumulation and erosion, to enter an ice cave is to be immersed in color, color that only ice can create. Our Ice Palace attempts to get close to this intense environment by creating vertical thick walls of dyed ice.” Photo: Bittertang Farm

Your work is incredibly colorful and whimsical. How did begin?

The playfulness I think is embedded in both of our personalities, and it probably started to translate to our work at UCLA. I think Michael and I were probably the only ones really going all out with color there. Color in architecture is, unfortunately, not used that much. You’re beginning to see it now more and more, but I think architects tend to just default to white walls. So Michael and I started looking at how to design with color — not so much as an application or a technique, but a link to the visceral.

Actually, our early conversations about coloration were almost like girls thinking about how to apply makeup: How do you achieve depth where depth doesn’t really exist? Or how does color produce new features in surfaces, essentially creating new forms? So rather than just thinking about how to apply paint to a building or to a material, we were thinking about how we might actually transform that material into something more substantial. And so color is now one of our main themes. We really try to work with color as a material in every single project.

Was there a before-and-after moment when you went from being interested in more standard architecture to your aesthetic of exploration and play?

I would say that my interest in experimentation and curiosity probably developed pretty early on. I was always curious to look for alternative solutions to even simple problems. I don’t think I was ever interested in being traditional with anything, so I couldn’t let my work as an architect be standard. I had to play.

Then I met Michael, and he was kind of similar. We learned from the great designers we had as professors, but we often shifted our understanding of design and architecture. So our ideas became more formal: the projects we designed in graduate school were about understanding more complex ways of drawing, putting things together in a physical model. UCLA definitely allowed us to focus on more complexity in forms and techniques. We did a lot of physical models and some pretty huge ones — because that was the only way we would be able to convince people that the things that we were imagining were actually being put together in a cohesive way.

That is where The Bittertang Farm inadvertently got its start – a partnership at first sight. Actually, we finished our degrees at the same time. Then Michael went out to New York that same summer, and I stayed in LA, before cutting out in March. We both ended up in New York working at two separate offices. We never decided to catch up later on and create a partnership — it sort of just happened. So we worked in New York, and at the end of 2009, I dedicated myself full-time to Bittertang. We started making a project together as The Bittertang Farm in 2008.

The descriptions that you have on the website — “Our work explores multiple themes including pleasure, frothiness, biological matter, animal posturing, babies, sculpture and coloration all unified through bel composto” — are wildly poetic and florid. But what do you say when you have to explain what you do?

The website’s language is kind of geared towards the design and architecture community, which expects a certain level of abstraction. Those texts are also meant to challenge the visitor and their expectations of what architecture is, because they are immediately confronted with a nontraditional language, definitions, interpretations and yes — our diverse interest and themes. My favorite is ‘babies!’ Michael was able to write a hilarious article on babies in art and architecture from the research we did on that topic. Ultimately florid and funny is the goal with the writing on the Bittertang website.

At the TED conference, trying to explain to people in a very short amount of time what we do at Bittertang was challenging but fun. I couldn’t be like, “Oh we work with pleasure, froth, babies, animal posturing and color all unified through bel composto,” because they probably would’ve been like “Whaaat?” Instead, I had to boil it down to how we design spaces using gases and liquids and create new building blocks in architecture with the help of pressurized membranes. That is still a little bit wild, but it proved to be more specific. The interesting part is that most people are able to pick up on our interests after the they see the images and really like the work, while others just don’t care anymore. It is also helpful to have a historical reference, like the work done with inflatables in the ’60s and ’70s, and to explain that we have added something new to the research, in that our pressurized membranes are no longer limited to air or gases but can also hold liquids, gels, soft mediums and biological matter.

In some crowds, I talk about a couple of our projects that were designed as a critique of how serious the profession of architecture has become, mainly advocating the importance of humor in architecture.

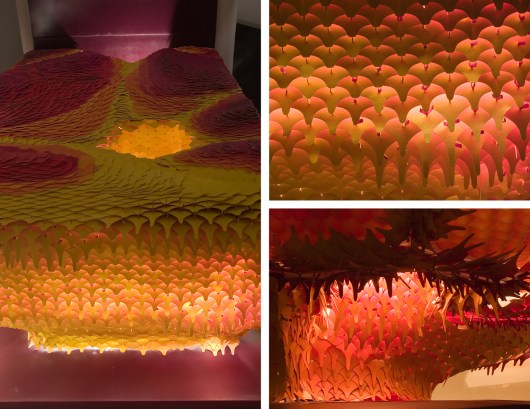

“In Big Bird, color is seen as a viscous material, it has the ability to move fluidly over space and emanate auras of reflected colors and particulate throughout space, thickening and extending boundaries.” Photo: Bittertang Farm

Question: What do you mean by ‘frothiness?’

Frothiness is something that always comes out in our projects — like color. Sometimes it’s as simple as creating material around predefined lines where you would expect to see a seam, but then you don’t necessarily see it because the material begins to froth — it erases straight edges with accumulation of matter. Frothiness can also be another way of creating texture and creating material that begins to bubble up, or materials that create sensations of being in clouds, or being immersed in froth.

We actually have a project that deals with literal froth, like foam. It’s a giant 320-square-meter sculpture that generates colorful foam of different colors. It actually becomes like a weather formation on a strange planet. The aesthetic aspect of frothiness comes from our interest in rococo and baroque architecture and art. They were the masters of froth. We’re just trying to figure out a way to get that into the conversation and materialize it in different ways where it’s not just made of plaster or stone, as it has been historically.

Do people come to you with commissions?

Our outlet so far has been winning competitions. Our first project for a competition was an aquaculture project, a fish farm. We answered the call for entries to a publication, and we were selected. That got us started. We started to experiment. And at first, we were more just researching, experimenting and playing around, just trying to see what was out there. In a year, we realized that we had five projects, and so we decided to apply for the Architectural League prize for young architects. We got the prize, which came with the opportunity to have an exhibition in New York and showcase the work.

Ultimately, we didn’t just show our portfolio, but instead we fabricated a new project just for the exhibition — we made a Succulent Piñata. It was the first time that we got some incentive to build something that wasn’t just for us, but for an exhibition. Immediately after that, we entered another competition with our first inflatable, and it was an international competition that we won. So yeah, most of our work right now is making projects in response to calls for submissions, but we carefully select the competitions we want to enter: they have to have our interests embedded in them.

Commissions are always welcome, though. We are ready!

How does the long-distance working relationship work? Does Michael come down to Mexico a lot?

It’s good. Obviously it’s not the same as when we’re together, but through Skype we get a lot of stuff done. There are lots of ways now to share your work and always have everything accessible for people. We have been doing this for over three years, now. Last year I was going a lot to New York as well. We do have strategic meetings where we meet physically every few months, depending on what’s going on.

“Blo Puff’s bloated body and furry innards acoustically, visually and olfactorally separates the pavilion’s interior from New York’s exuberance, allowing the naturalized interior atmosphere, views to the sky and the interior space to be enjoyed without distraction. The interior, protected by a thick envelope, becomes a place of relaxation, reading and eating, where visceral and cerebral can be enjoyed with equal pleasure.” Photo: Anna Ritch

When you make an installation together, do you just meet wherever you’re going to be and then put it together there? Doesn’t that pose technical difficulties?

Let me tell you about our first winning project, titled Blo Puff, a pavilion we built at Union Square in New York. When we were notified that we had won the competition, we had something like two and a half weeks to pull everything together. Turns out two and a half weeks to do something that you’ve never done before is not enough time. I started looking into finding the person who was going to make this inflatable, and every available manufacturer that we came across in that short amount of time proposed to built our project with qualities we didn’t want: all the options pointed towards us showing up at Union Square with a pavilion that would have looked like a jumping castle — obviously not an option for us!

We were very naïve at that point about how you make a transparent, translucent inflatable. The difficult part was that we knew it had to be airtight — meaning it couldn’t have a fan that would circulate air all the time. That’s the other advantage to the work that we’re doing with inflatables: before, they always needed a fan running. We found a company in Seattle that said, “Yeah. We’ve never done it, but we could probably figure it out — we have the air valves, the transparent membrane and the sealers.” We knew immediately this was our best chance. They didn’t do inflatables, but they had the right material and technology — they seam together different types of tarp material for various applications. All we had to do was teach them how to do it — which we were teaching ourselves by making small prototypes down here in Mexico.

So the project was designed between Guadalajara and New York, and then I had to go from Guadalajara to Seattle for a week to go to the factory. They gave me a team, and we had to train them how to cut the patterns and how to seam it. And then in the process, the competition people were like, “This museum in Tel Aviv really likes your project. They want to know if you can actually make a replica in Tel Aviv.” And at that point we didn’t know if we were going to have one done! But if we were going to figure out how to fabricate one, I guessed we could get two done.

Next thing we knew, I was flying out of Seattle at 11pm, and we’re packing two inflatables at 8:30pm. I went straight to JFK, and at that point Michael met me. He took off with one bag to Tel Aviv and I stayed in Brooklyn. So we had these two installations going on simultaneously around the world, and it all happened within three weeks.

We also had to find these other materials — natural materials, like eucalyptus leaves, Spanish moss, a custom-made net that Michael’s dad ended up fabricating for us because he’s an ocean engineer. Our projects take on a life of their own and help us figure out so much along the way, because nothing is really set.

Another example is Burble Bup, the summer pavilion we built in 2011, which was much bigger — it was the biggest structure we’d done to date. It was a similar process — Mexico, New York — but then more than 200 volunteers came to Governor’s Island, over a period of three weeks, to help us built this pavilion. Even the jury who chose our project didn’t really believe it could be done. It stayed up for four months and survived a hurricane, and more than 100 thousand people that visited the island that summer.

“Built of tactile materials, the Burple Bup pavilion is a place of touch, interaction, play, and humorous social engagement. Thin membranes hold air and wood chips in bizarre and colorful volumes, attracting people to play underneath its dangling canopy and engage with their environment and neighbors in strange and interesting new ways.” Photo: Bittertang Farm

Would you want to take these pieces and then try to get them staged around the world? What is your ideal trajectory for your work now?

We want to continue exploring and discovering new things about our work and ourselves. At the moment I am very excited with the range of materials that are planning on tackling so that we can continue to create engineering marvels and more fantasy experiences and dream spaces. We would love to parade our easily transportable projects around the world. At the end of last year, we actually proposed five projects in three different continents and that is great because we learn so much from the different environments with every proposal built or not. Commissions of course are very important for us and for our work to growth and to transform our current resources so that we can more effectively tackle the permanent and scale questions of pressurized membranes. Ideally we want to continue to build at all scales so that our work remains prolific and hopefully self-sustaining and profitable — so that we can continue to bring happiness and pleasure to our built world.

What about things that are more permanent? Do you see building with pressurized membranes, with gases and liquids, as something that’s a sustainable building material that could last over time?

It is a little bit difficult to imagine that this could become advantageous for more permanent solutions, but I think there are a lot of ways this can actually be done. Right now we’re just experimenting with the basic kit, which is plastics. We understand plastics: some plastic membranes are easily wrecked. You can puncture them. But there are other materials out there that right now we don’t have the means to get at, but they can actually hold things very well — they can make architectural elements and structures more permanent. Building architecture out of soft elements is quite difficult, but our small-scale interventions have already begun to address that issue. We have so far built walls and canopies out of transient material — such as gases, liquids and biological matter — and we have been able produce strong and resilient building blocks.

We are also interested in making things that might be applicable in space. We’re always trying to redefine physics in our projects through poetic dream spaces and so on. But we’re also interested in what happens when you have to build under difficult constraints or under different physical laws; this work is applicable in that direction as well.

How serious are you about the sustainability angle of it?

I am very serious, but I think the word sustainability is so charged nowadays with so many different ideas and issues in architecture, it has made us try to figure out a way to talk about it without attaching ourselves to the sustainable movement in a traditional way. With our projects, we’d rather address biological matter and talk about how to shape our projects as living systems. For example, we’re trying to encourage our membranes to develop growth, interact with nature and allow the natural environment to take over, such as mushrooms that ended up growing out of the organic materials stuffed into our pavilion. It was great to meet people at TED that are doing such work already — people who are growing materials. Just in the TED Fellows community, Suzanne Lee grows her own clothes. Rachel Armstrong is developing a material to restructure Venice’s docks and foundations, and so on. Designing and building with biological matter is already a step towards a more serious and exciting sustainable future.

One of the fascinating things about your work is that it is so physically intimate. People are invited to crawl into, touch, jump on your built environments. It looks irresistible.

Yeah. It has to be! For some reason, we feel responsible for encouraging pleasure through our work and allowing people to engage our spaces in a more interactive and physical way than by just looking at it. We are always bringing pleasurable elements within the reach of people. That is something that I think is not achieved or is not in the interest of some of the mainstream architects and their buildings. Our goal is to also take the intimacy of physical space to a larger scale.

The visceral experience of our work is very important for us, and sometimes it’s very literal. Every time we get a chance to get people to interact with our projects, their responses are very rewarding to us. They come up with ways to engage with our spaces that we wouldn’t thought of. And the children — definitely our favorite clients!

Comments (8)

Pingback: A “living” amphitheater blooms, Edward Snowden gets graphic, and a new algorithm for Google … - The Online List

Pingback: A “living” amphitheater blooms, Edward Snowden gets graphic, and a new algorithm for Google … | BizBox B2B Social Site

Pingback: A “living” amphitheater blooms, Edward Snowden gets graphic, and a new algorithm for Google … - Rixal Communications | Custom Media & Advertising | Media. Solved. | Rixal.com

Pingback: One Ring to rule them all: Antonio Torres’s design firm Bittertang to create an organic outdoor amphitheatre | TEDFellows Blog