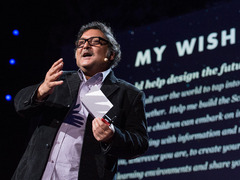

Last week, education researcher Sugata Mitra won the first-ever $1 million TED Prize to build his School in the Cloud.

Last week, education researcher Sugata Mitra won the first-ever $1 million TED Prize to build his School in the Cloud.

Sugata Mitra: Build a School in the Cloud

Prior to his TED Prize win, Mitra was known for his “Hole in the Wall” experiment. In 1999, Mitra and his colleagues dug a hole in a wall near an urban slum in New Delhi, installed an Internet-connected PC and left it there — while a hidden camera filmed the area. Through the video feed, they observed children from the slum playing around with the computer, teaching themselves how to use it and sharing with others their amazing discoveries.

Sugata Mitra: Build a School in the Cloud

Prior to his TED Prize win, Mitra was known for his “Hole in the Wall” experiment. In 1999, Mitra and his colleagues dug a hole in a wall near an urban slum in New Delhi, installed an Internet-connected PC and left it there — while a hidden camera filmed the area. Through the video feed, they observed children from the slum playing around with the computer, teaching themselves how to use it and sharing with others their amazing discoveries.

At TED2013, Mitra invited the world to embrace child-driven learning by setting up Self-Organized Learning Environments (SOLEs) and helping him design a learning lab in India, where children can “embark on intellectual adventures.”

We gave Mitra a call and asked him to reflect on his TED Prize win, dive deeper into his thoughts about learning and share the personal experiences that inspired his passion for igniting curiosity in children across the globe.

Here’s our conversation:

What does winning the TED Prize mean to you?

To me, it is a great symbol of recognition — that my work of the last few decades does have acceptability and is of real interest to the world. I was nervous that my work would get put aside as “out of the box,” a phrase I dislike immensely, and forgotten. I am more confident now, thanks to TED.

How did your upbringing shape your interest in self-directed learning?

I did not know anything about self-directed learning until 1999 when I stumbled upon it because of the Hole in the Wall experiment. I grew up more or less by myself in a big bungalow in Delhi with a large garden that had lots of trees and all sorts of birds, animals and insects. We used to learn together, if that makes any sense.

If you were part of a SOLE as a child, what big question do you imagine you might have asked first?

I think I have always been in a SOLE. I grew up quite alone and used to experiment constantly with my surroundings — trees and animals and birds and myself. There were no computers, so I used to ask questions to nature, and often, she would answer.

What is the first thing you remember learning on your own? Did you enjoy the process?

When I was 4 or so, we used to live in my mother’s house in Calcutta. The morning newspaper was rolled up and tossed into our first-floor balcony by the newspaper man. I was always up very early and used to pick it up and take it to my grandfather. I did not know he was dying from cancer. One day when I went to his room with the paper, it was empty and there were people crying. I went back to the balcony and put the paper back where it had fallen and stood for some time wondering if I should pick it up and try again. I learned you can’t turn back time. I did not enjoy the process, I am afraid.

Some people have misunderstood your strategy as anti-teacher, when in fact you are arguing that teachers have a crucial role to play — just a different one — in this technological age. Who was your favorite teacher and why?

My favorite teacher was Father Lewicki at St. Xavier’s High School. When I was 16, I told him I don’t see why I should believe in God. He said I should read Teilhard de Chardin and decide for myself.

Will child-driven education work differently depending on a child’s culture, gender and access to resources?

Easy access to an unsupervised, publicly visible computer with broadband is critical. But children are impacted differently depending on their reading comprehension, particularly in English. Culture does not matter so much when you are dealing with 8-12-year-olds. Neither does gender.

How has parenting informed your perspective on self-directed learning?

My father did his Ph.D. under Benjamin Bloom in Chicago, in the days of objective-driven and “programmed” learning. He then became one of the first psychoanalysts in India. I think he taught me a lot of things by not telling me to do things — by not teaching and only listening.

I learnt how to listen and that people will tell you everything if you listen and say “hmmm” once in a while. My mother, who was once a student of Rabindranath Tagore, taught me how to do lots of things just by thinking about them.

Your Hole in the Wall experiment inspired Vikas Swarup’s novel Q & A, the book that Slumdog Millionaire is based on. How do you think your TED Prize wish will impact popular culture?

In an age where “knowing” may be obsolete, Homo sapiens will have to reinvent ourselves. The wish, I hope, will be a tiny step in that direction. If children have wings, they will learn how to fly.

Did your experience as a parent impact your views about self-directed learning?

The Hole in the Wall experiment was based on what I had learned from my son when he was 6. It was 1987 and I had bought my first PC, spending nearly a year’s salary at the time. When it arrived, I said to my son, “Don’t even think about it.”

About three days later, I was looking for a file on the DOS system. Every time I typed DIR, all the file names would scroll up too fast for me to read them. As I was trying the third time, a little voice from behind said. “If you type DIR/W/P, it will show up like a page.” I was a bit shocked. “How did you know that?” I asked. “Well, that’s what you did yesterday!” he said. From then on, I let him use the computer.

In a couple of weeks, I was asking my son how to do things that I did not know my computer could do. I wrote a paper suggesting that children can learn to use computers by themselves just by watching each other. It was very badly received. Twelve years later, in 1999, my friend and employer Rajendra Pawar let me do the Hole in the Wall. He had no clue what I was trying to find out. The rest is history.

Comments (5)

Pingback: The Future of Learning in the Digital Age – Charlotte's Blog

Pingback: Articles of Interest – March 8, 2013 « National Creativity Network

Pingback: What if students learn faster without teachers? - catchup24

Pingback: One Direction news, pictures, lyrics, and albums

Pingback: Wizmo Blog » Blog Archive » Before the Hole in the Wall: A Q&A with 2013 TED Prize winner Sugata Mitra