Tshering Tobgay speaks at TED2016 – Dream, February 15-19, 2016, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

In the final session of TED2016, the themes we’ve been talking about all week — the progress of society, the measure of personal success, the importance of the environment — snap into focus. From the prime minister of the “world’s happiest country” to a pair of speakers who challenge the traditional American Dream, it’s a session that will inspire, make you question and doubt, and send you out into the world ready to force change.

The happiest country on Earth, in danger. Bhutan is a country of 700,000 people in the Himalayas, sandwiched between two of the most populated countries on Earth, China and India. But Bhutan is a little different, says Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay. “For Bhutan, Gross National Happiness is more important than gross national product,” he says. Education and healthcare are free, and the environment is a priority: Bhutan was the first country to go carbon neutral, forest protection is written into its constitution, and it exports hydropower. “Today, the clean energy we export offsets six million tons of co2,” he says, and by 2020, that number will increase to 17 million tons. But Bhutan is a mountainous country of glacier lakes, and as they melt, the effects are devastating. “My people have done nothing to contribute to global warming, but we are already bearing the brunt of its consequences,” he says. Tobgay sees hope in the recent Paris Agreement. But still, his government is thinking proactively on how to keep leading the charge. They have set up Bhutan For Life, a Kickstarter-like campaign to fund environmental protection and the nation’s system of parks. He asks: what if this campaign went global?

Why are babies dying? Before Sue Desmond-Hellmann worked in public health, she was an oncologist. Now, the CEO of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is turning to infant mortality. Being a scientist at heart, she’s been shocked by how little we really know about what’s killing the world’s 2.6 million babies that die before they’re even a month old. A surprisingly large number of these babies die from what’s logged as “neonatal”—except, as Desmond-Hellmann says, “’Neonatal’ is not a cause of death; it’s simply an adjective.” It means: We don’t know why. We can’t be precise. So Sue is advocating for a new approach to “precise public health,” to use data to find where treatment is needed most. The method has been effective before, in reaching pregnant HIV-positive mothers. To apply that approach to the death of babies, Desmond-Hellmann and her team are working to painstakingly collect and log information on neonatal deaths in the developing world, through difficult conversations with mothers. If they meet their goals in the next 15 years, says Desmond-Hellmann, they can save 1 million babies’ lives every year. But first: They need more data. Because, as she says, “You can’t fix what you can’t define.”

Stephen Wilkes speaks at TED2016 – Dream, February 15-19, 2016, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

A relentless collector of magical moments. Photography can be described as a recording of a single moment, frozen in a fraction of time. Photographer Stephen Wilkes breaks this paradigm — his photos collapse time, compressing the best moments from night and day into one image. His process, which he calls Day to Night, begins by photographing iconic locations from a fixed vantage point 50 feet or more above the ground, capturing thousands of images across 30 to 50 hours. He then chooses the best moments from day and night and seamlessly blends them together into one beautiful, sprawling image. “I believe these photos begin to put a face on time,” he says. “They embody a new metaphysical reality.” Wilkes shared time-bending photos from Serengeti National Park, from the second inauguration of Barack Obama, from Paris and Times Square. “I am exploring the space-time continuum within a two-dimensional photograph,” Wilkes says. “I’m compressing the day and night as I saw it, creating a unique harmony between these two discordant worlds.”

More choices for refugees. A million refugees arrived in Europe this year, says Alexander Betts, and “our response, frankly, has been pathetic.” Betts studies forced migration, and he believes the issue isn’t that people don’t care about refugees. And it’s not that there aren’t rules — the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees lays out shared global responsibility for refugees. The “inhumane response” is because we “lack a vision”: we see refugees as about them, about “letting them in,” and not about us, how refugees can make the world better. As of now, 1% of refugees will get legal resettlement in a new country. It’s a “lottery ticket,” says Betts. Another 9% will go to a refugee camp, which are bleak and offer no opportunities for work or education. Some 75% will head to urban area in a neighboring country, where they’re often not allowed to work. The rest risk lives on perilous journeys to another country; they roll the dice for opportunity. “We can expand that choice set,” says Betts. For one, we can grant refugees the right to work — either at large or in specific zones. Uganda has done this, and in Kampala, its capital, it’s estimated that 21% of refugees own a business, many employing locals. We can think about preference matching between refugees and host countries, asking countries what skills they need and helping connect them with people who need to resettle. We can offer humanitarian visas, obtainable near conflict zones, that lets refugees pay for a ferry and a cheap flight to another country instead of a dangerous, expensive, often deadly journey with a human smuggler. This would undercut the smuggler market — and remove chaos. “There’s nothing inevitable about refugees being a cost,” says Betts. “They are human beings with skill, aspirations, talents and the ability to make contributions if we let them.”

A David Bowie tribute. After a short break, the stage turns pitch black. Violin and cello began to hum as the familiar countdown to “Space Oddity” begins …“10, 9, 8 ….” indelibly voiced by Al Gore. Musician Amanda Palmer gave us her version of the David Bowie classic, accompanied by string quartet and the guitar of TED Fellow Usman Riaz. Shortly after Bowie’s death, Palmer and friends recorded five of his songs for Strung Out in Heaven. The record is for sale, and proceeds go to cancer research.

Amanda Palmer performs at TED2016 – Dream, February 15-19, 2016, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

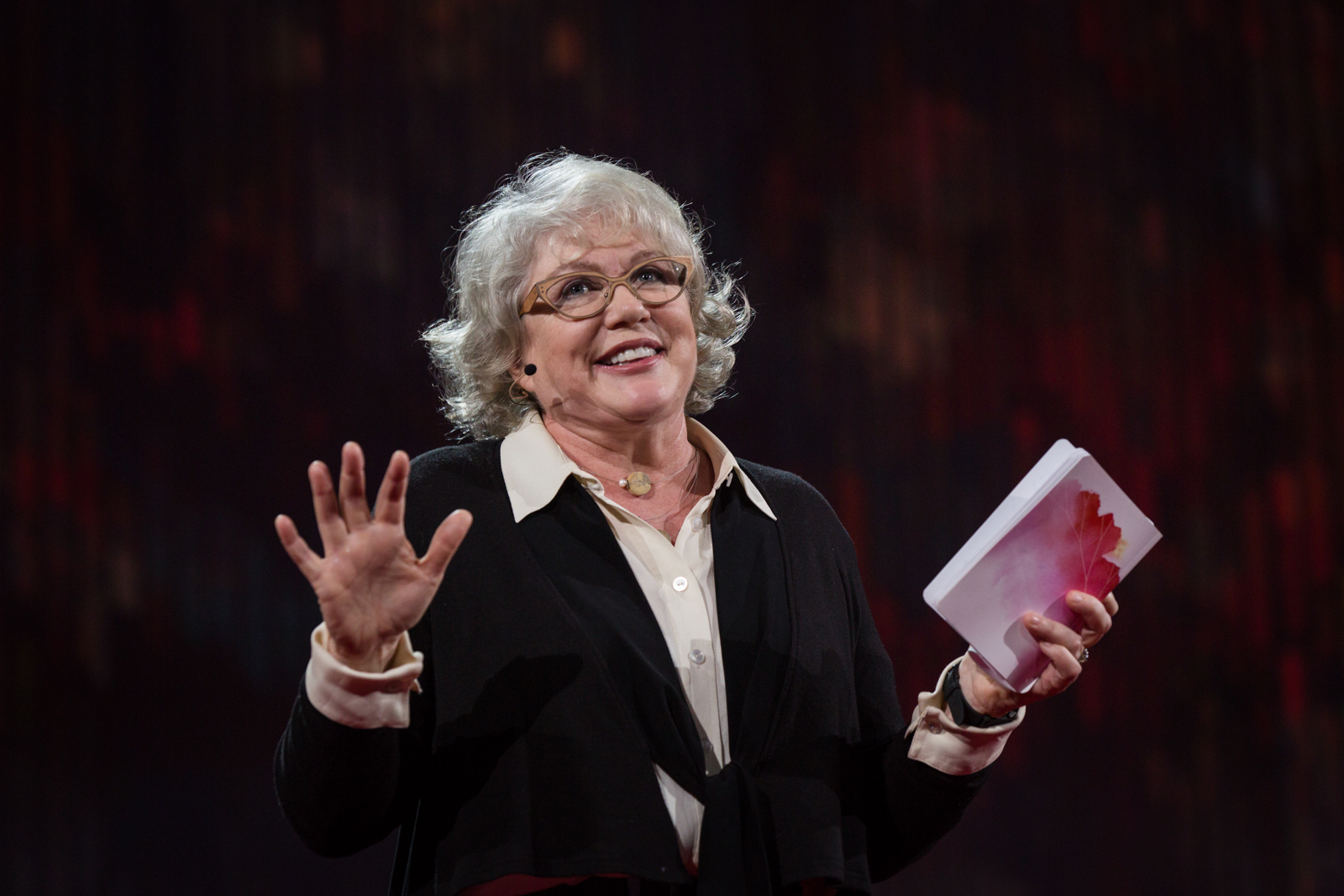

The words of TED2016. Do you know what a magnetar is? Are you a precrastinator? And what is real meaning of the word moonshot? Lexicographer Erin McKean takes a look at the best words used onstage at the conference, explaining what they mean and how to use them. Read her list of the best words of TED2016.

The 21st-century “good life.” “For the first time in American history,” says journalist Courtney Martin, “the majority of parents think their kids will not be better off than they were.” But that’s not a reason for panic or depression; rather it’s the perfect moment to redefine what exactly we mean by “better off” and reevaluate our reach for more, more, more. We focus too much on getting secure jobs, earning as much as possible, living in houses with white picket fences — the classic tropes of the American dream. But in a time of financial uncertainty, that’s not how we’ll define the good life in the future. Indeed, she says, “The art of living well is often practiced most masterfully by the most vulnerable.” She urges us to move toward a new flexible approach to work and family that accounts for what we care about, and to look for alternative living arrangements. We need portable health policies, universal basic income. “The biggest danger is not failing to achieve the American Dream,” said Martin. “The biggest danger is achieving a dream that you don’t actually believe in.”

There will be no miracles here: Casey Gerald traces the drama of his life back to an East Texas church on the night of December 31, 1999, when his savior did not come for him. As he searched for a new one, at Lehman Brothers, as a staffer for Barack Obama, at Harvard Business School and at a nonprofit he founded to help social businesses … still his savior did not come. Now, he’s believing in something new — a gospel of doubt. Find out more about this new gospel in a full recap of his talk.

TED, the sitcom. “This is basically my experience at TED,” says comedian Julia Sweeney, who’s here to wrap up the conference. “I’m listening to a talk and get so overwhelmed by what the person is talking about. … I realize that our brains are in sync, and I get all verklempt.” She thinks her life is changed — that nothing will ever be the same. Then she’s in the lunch line and sees that speaker — and she has no idea who it is. When she’s reminded, she thinks, “Oh, but that was the morning session.” TED is a marathon of ideas. And as she pokes fun at many from the week, she spins out sitcom ideas that she hopes Norman Lear or Shonda Rhimes might consider making. The procrastinator-and-precrastinator version of The Odd Couple, perhaps? A version of The Golden Girls starring herself and Mary Norris? In the end, Sweeney concludes that TED is an incredible but overwhelming experience. “This needs to be a month long, with one idea per day,” she says, “then we just lay in the fetal position.”

Julia Sweeney speaks at TED2016 – Dream, February 15-19, 2016, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Ryan Lash / TED

Comments (2)