Bruce Haden speaks about his brother, a well liked and respected lab technologist, and a drug dealer. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Audience members give talks during a session of TED University. From Ebola to better businesses, from diabetes to disasters, the talks took on big topics:

A type-A response to Type 2 diabetes. Kicking off the session, Laurie Coots shares her personal story of how she beat Type 2 diabetes and regained control over her health. For Coots, a type-A global executive with a fast-paced lifestyle, managing her diabetes was not an option — she wanted to beat it. Over a five-year journey, Coots realized that she had to imagine her future healthy self and live that live in the present. She broke down her journey into little battles and came up with strategies to win them. Using tricks like eating with smaller plates, or eating everything (even a Snickers bar) with a fork and knife, Coots got her eating habits under control. “Start eating like your life depends on it,” she says. “Because it does.”

A different kind of drug death. Architect Bruce Haden has a personal story to tell about his younger brother, Paul. On the night of June 7, 2008, Paul was found dead in his apartment — he was purifying 2.2 kilos of street ecstasy, still on the stove. “When he died, he was a well-liked and much-respected lab technologist at a hospital. He loved science,” says Haden. “He was not a drug dealer in the usual sense — he was an activist. He believed that drug use was an ingrained part of any advanced civilization” — and he worked to make clean, safe drugs for the people who used them. Haden doesn’t want to make his brother sound like a hero. “It’s hard when someone you’ve loved your entire life has passions that are illegal and dangerous,” he says. But the message he wants to share today: that treating drug use as a criminal justice issue has a toll. “As the creators of the current system of prohibition, those deaths are our responsibility,” he says. “We have blood on our hands.”

A fatal market failure. “For the last year, Ebola has stolen all our headlines and fear,” says epidemiologist Seth Berkley. Despite how hard it is to catch Ebola, the risk of death once you’ve caught it is incredibly high, and there’s no treatment. “It seems,” says Berkley, “to defy modern medical science.” So why is it taking so long to find a vaccine? It comes down to one thing, says Berkley: the people most at risk are the people least able to pay. “For Ebola,” he says, “There’s absolutely no market at all.” To avoid this problem in the future, says Berkley, at an early stage of an outbreak we need to: 1. Recognize the lack of market potential; 2. Build laboratory and outbreak investigation capabilities; 3. Create repositories of potential agents and better catalogue their immunologic properties; and 4. Develop vaccine vector platforms. Now, says Berkley, pulling two vials out of his pocket, there are two Ebola vaccines in efficacy trials in the Ebola countries. Following his steps, next time, we can be even more prepared.

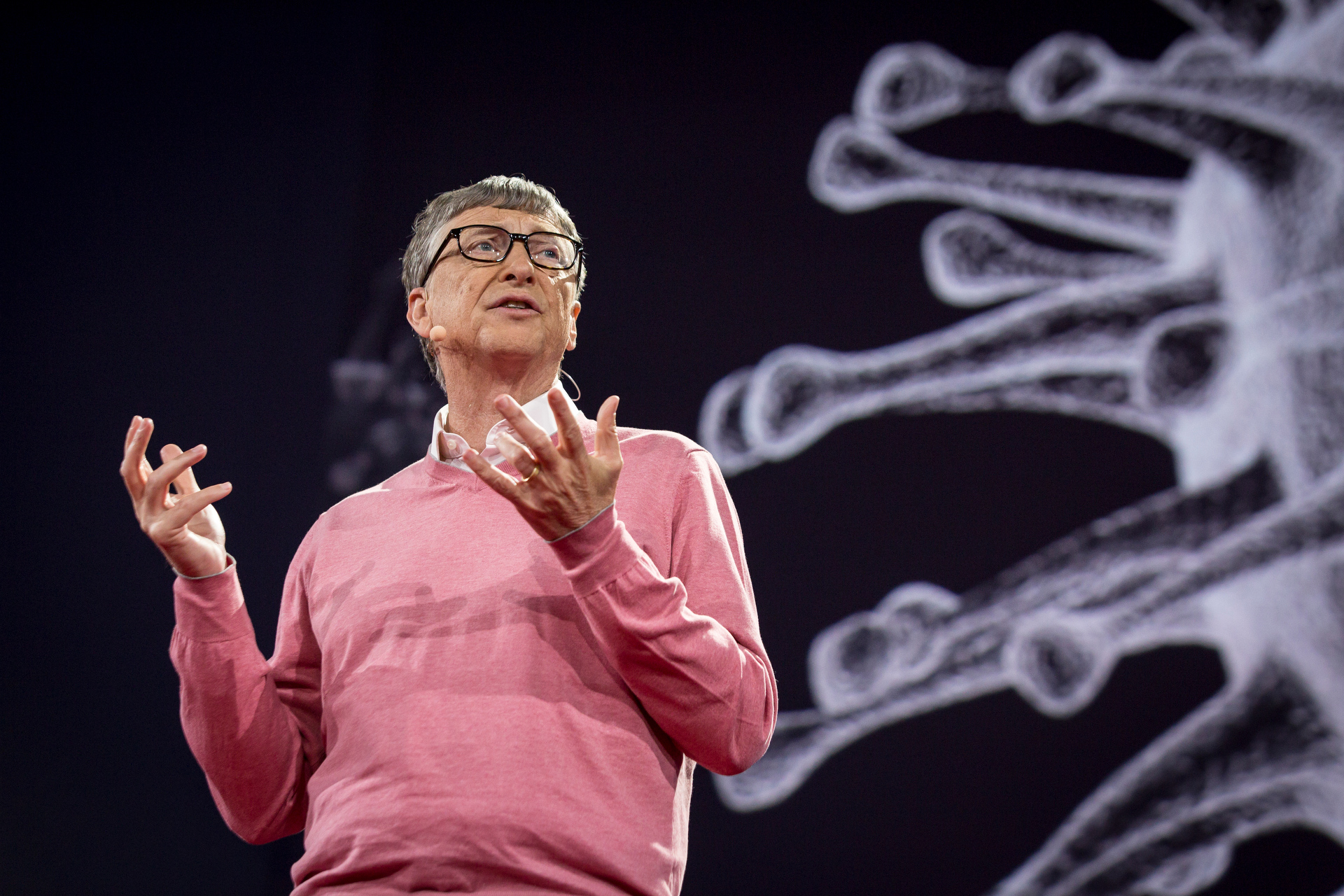

Bill Gates shares lessons learned from the Ebola epidemic. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

The next epidemic. Next up is Bill Gates, who shares lessons learned from the Ebola epidemic. Thanks to heroic work by health workers, and the nature of the Ebola virus, the disease was relatively contained to certain areas. But, Gates warns, we are not ready for the next major epidemic. A highly contagious flu epidemic could kill up to 30 million people, and lead to a drop in global wealth of $3 billion. Learning from the gaps in the response to the Ebola virus, Gates outlines 5 key elements necessary to a robust and effective response system for next time:

1) Strong health systems in poor countries. With stronger health systems, all kids are vaccinated, and it enables doctors to detect the outbreak early on.

2) Medical reserve corps. A team of professionals ready to respond to an outbreak at any time.

3) Pair medical and military. Take advantage of military’s ability to move fast through areas and adapt to new places.

4) Run germ games. Run stimulations to see where holes are (not war games)

5) Kickstart advanced research and development in vaccines and diagnostics.

“We need to get going,” says Gates. “Time is not on our side. If there’s one positive thing that can come out of Ebola epidemic, it’s that it can serve as early warning, a wake-up call to get ready. If we start now, we can be ready for the next epidemic.”

A natural disaster we can prevent. “We can’t stop what we can’t see,” Valerie Conn, vice president of strategy for B612 Foundation’s Sentinel Mission, reminds the TED audience. Conn is talking about the 1 million potentially dangerous asteroids rocketing through our solar system. Of these 1 million, only 12,160 have been found. That leaves 987,840 asteroids undetected. In 2013, an asteroid crashed into Chelyabinsk, Russia, injuring 1,500. “We had no advance warning,” Conn says. “World space agencies and governments first learned about that asteroid on Twitter.” The solution is to build more telescopes, train them on the skies and put the data we gather into action. “Asteroids,” Conn says, “are one natural disaster we know how to prevent.”

As we lay dying. The average life span in the mobile game Crossy Roads is 17 seconds. Struck by how much time he was spending happily playing this game and dying over and over, ad guy and one-time game developer Renny Gleeson set out to calculate how many people die in video games every day (the death rate over time – or D-ROT, if you will). Here’s what he learned:

1. You never die alone. A team of animators and designers have made sure you’re going to have a great death.

2. Muzzlefire is the new campfire. Games allow us to have conversations we otherwise couldn’t.

3. “Death” is never “the end.” Actually, says Gleeson, “The saddest moment in a videogame is not when you die, it’s when you win and the game is over.”

Oh and the D-ROT? 1.2 billion people – that’s the entire world’s population that dies every six days.

Eric Lewis (Elew) introduces TED2015 to rockjazz. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Energetic rockjazz. Leaning against the piano like a sprinter in mid-stride, Eric Lewis, also known as ELEW, opened with an exuberant, powerful yet light melody with a rock-like sound. One hand under the piano’s lid, he simultaneously emulated swift touches on a cello by plucking the piano’s strings. He then bridged to a softer, jazz-like section that both calmed and prepared the audience for the unexpected. Then, he revved up to a race between high and low notes, competing, in tandem, to create what felt like a celebration, a release. With notable influences of bands such as Coldplay and Radiohead, Eric Lewis’s “Rockjazz” style was a joyful addition to the session.

Let’s get more women in the news. “Picture a place where women are only seen 24% of the time,” says Alisa Miller, the CEO of PRI. “That’s what global news media serves up to you each day … and when women are seen and heard, we’re all too often shown as objects and victims.” This distortion damages everyone, she says. It not only makes women feel helpless and cynical, but creates a wide “empathy gap” that leads to harassment via social media. So what can we do? According to Miller: (1) increase the level of women in news leadership, and cover more women in the news, (2) push social media companies to provide tools to combat harassment, and (3) spread newsworthy stories about women. She ends with an anecdote about Alanah Pearce who, when she gets harassed online, looks up the harasser—and shares with their mother what they said.

Do we know what we know? Our minds trick us in our tastes and physiology – but what about when it comes to matters of social justice? Behavioral economist Dan Ariely reveals some new information about how much people actually know about inequality in the US, underscoring the gaps in our knowledge — and the gap between our expectations and our ideals. The people he surveyed believe that the top 20 percent of the population hold 58.5 percent of the wealth, while in reality it’s 84.4 percent. Even more interesting is that surveyed people think it should be about 31.9 percent. Says Ariely, participants didn’t want full-on socialism, but they definitely wanted things to be more equal than they are.

Alisa Miller argues against a world where women lead the news only 24% of the time. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Our profit mania. “We have somehow come to view companies in a narrow and monomaniacal fashion, focusing almost exclusively on short-term profits, quarterly earnings, and share prices at the expense of all else,” says Paul Tudor Jones II, the founder of Tudor Investment Corporation. He shows two graphs that highlight the issue: first corporate profit, which, at an average of 12% of revenue, is at a 40-year high. Since 10% of families in the US own 90% of stocks, this only serves to increase income inequality. The other graph: corporate giving as a percentage of profits. It’s dipped dramatically over the past few years. “Given that we are at peak profit margins, does this really feel right to you?” he asks. To read more about this talk, and his bold promise for his own corporation, read a full recap of this talk.

Designed in China. Design scholar Lorraine Justice takes us on a whiplash-fast tour of designers in China working in commercial arts. Look them up: Guo Pei, a fashion designer in Beijing whose work is all about fantasy and color; Ma Ke, a designer from Southern China who focuses on natural materials; Neri & Hu, product designers who use a clay from local lakes to create products; He Jianping, who takes Chinese calligraphy and abstracts it; and finally, Nosk, a mask that covers the nose, designed by a group of students to replace the paper face mask. Her point: China has 1,000 industrial design programs at the moment while there are 53 in the United States. And fascinating work is on the way.

Lorraine Justice presents visionary designers from China. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

The world in 4D. Rick Smith believes that 3D printing is going to change the way things are produced in our modern world in a more drastic measure than the Industrial Revolution has in the last three hundred years. It will require a complete restructure of our global approach to production. Instead of the model of mass production, a new manufacturing system will gain ground, favoring customization, flexibility and localization. There’s more. Imagine a world in 4D. These would be printed 3D pieces that are programmed to activate when their environments change; when they get cold, or are put into water. Imagine a pipe that knows to fix itself if it’s damaged, or an artificial bone that releases medication and painkillers over time. Smith sees a future in 3D and 4D. “Rarely in history,” he says, “has there been a technology that offers so much promise and so much threat of disruption.”

What makes a good startup? As the founder of Idealab, Bill Gross incubates new tech companies. On the TED stage, he shares the surprising keys to success for startups. After analyzing five factors for success at 100 companies spawned at Idealab, as well as other big companies like Instagram and YouTube, Gross was surprised to find that more than the idea or the team, or the business model or the funding, the most important factor that determined whether a startup took off or floundered was this: timing. Take AirBnB, for example, a company that was famously passed over by investors many times. Conventional wisdom said that no one would want to rent out their homes to strangers — until the 2008 recession hit, and people’s need for extra cash overtook their hesitance to welcome strangers into their homes. Execution matters a lot, and the idea certainly matters as well. But, Gross says in conclusion, what you really need to ask yourself before launching a new startup: Is the timing right?

Business has become boring. Says marketing expert Tim Leberecht, “We’re engineering the romance out of our lives.” We’re measuring to optimize, he says, and as a result, “It seems that only the measured life is the good life.” To put the romance back into business, he thinks we need to create a romantic experience for our customers with more mysterious, ephemeral products like Snapchat and Secret Cinema. Says Leberecht, “Knowledge might be power, but not knowing might be the more powerful.” He also recommends “being a stranger in a strange land.” On the way to work, talk to someone you don’t know. At the office, swap desks or even roles for the day. “Many of us spend the majority of our waking hours at work,” says Leberecht. “Let’s romanticize the enterprise.”

Tim Leberecht is trying to bring romance back to engineering. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Comments (2)