It’s been an unforgettable eight weeks of TED2020, the first-ever virtual TED conference. For the final session: a call to moral leadership, a rethink on what it means to be a citizen, some pointers on how to make a good argument from a Supreme Court litigator and much more. Below, read a recap of the inspiring ideas by amazing speakers (and check out the full coverage of the conference here).

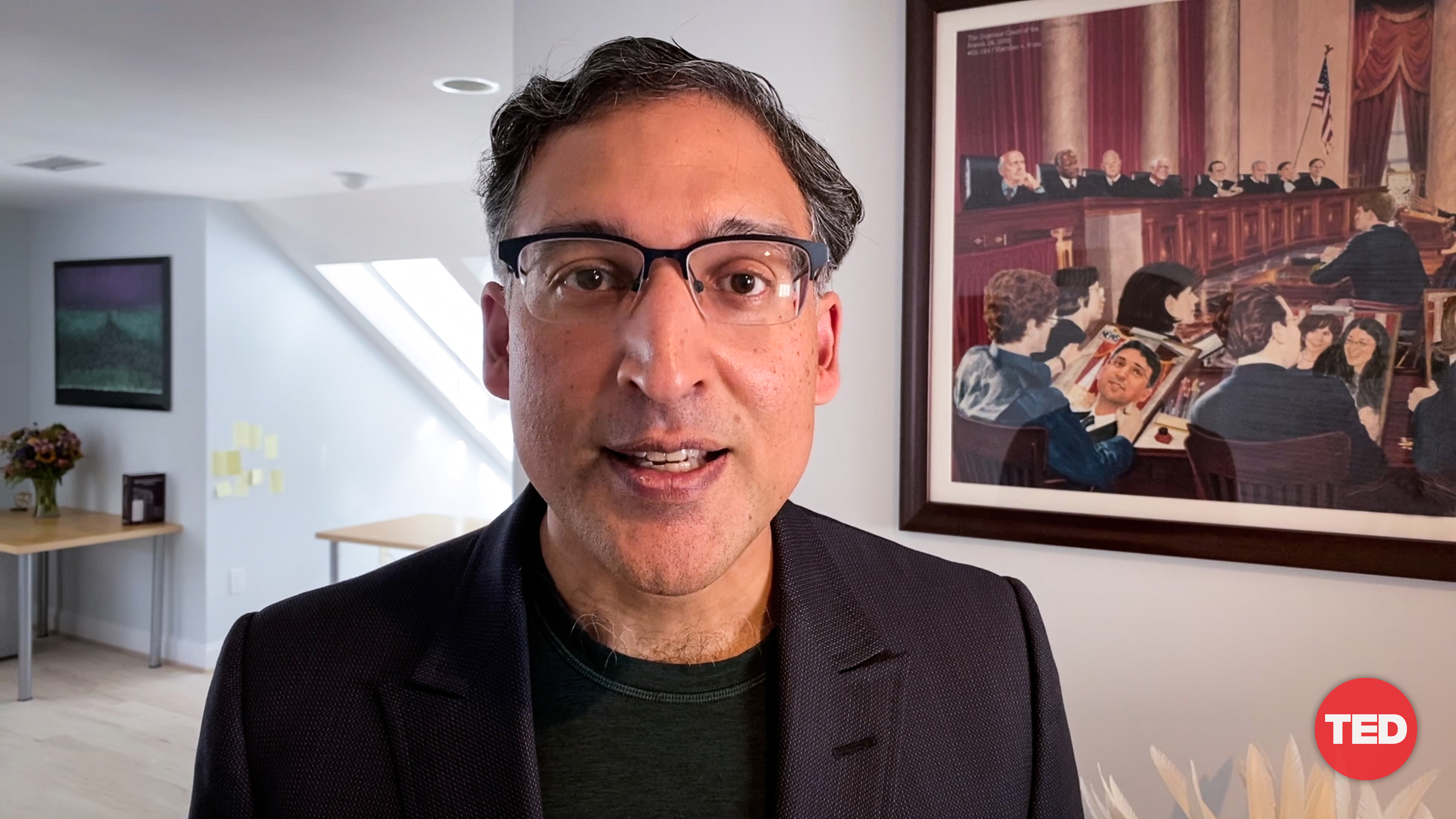

“If you make a good argument, it has the power to outlive you, to stretch beyond your core, to reach future minds,” says Supreme Court litigator Neal Katyal. He speaks at TED2020: Uncharted on July 9, 2020. (Photo courtesy of TED)

Neal Katyal, Supreme Court litigator

Big idea: Empathy and long-term drive are key to crafting persuasive and successful arguments.

Why? Winning an argument isn’t just about drowning out an opponent or proving them wrong — it’s about leveraging empathy and human connection to draw a comprehensive understanding of the circumstance and, ultimately, highlight the most just solution. As a Supreme Court litigator, Neal Katyal has argued some of the most impactful cases of recent history, including the case against the 2017 Muslim travel ban and the case against waterboarding and Guantanamo Bay military tribunals. In his experience, he realized that while good courtroom practices include extensive practice and avoiding displays of emotion, crafting a successful argument takes more. Sometimes arguments fail — and it’s at that moment of failure that empathy is most important. Katyal hasn’t won every case he’s argued, but through failure he’s been able to better understand the core of his work and refine his arguments to resonate more deeply. By drawing strength and drive from our personal histories and principles, we can identify why our arguments advance justice and how we can articulate it more clearly to our opponents. “The question is not how to win every argument — it’s how to get back up when we lose,” Katyal says. “In the long run, good arguments will win out. If you make a good argument, it has the power to outlive you, to stretch beyond your core, to reach future minds. Even if you don’t win right now, if you make a good argument, history will prove you right.”

“America is above all an idea, however unrealized and imperfect, one that only exists because the first settlers came here freely without worry of citizenship,” says immigrant rights advocate Jose Antonio Vargas. He speaks at TED2020: Uncharted on July 9, 2020. (Photo courtesy of TED)

Jose Antonio Vargas, immigrant rights advocate

Big idea: Americans need to identify their own immigrant narratives — and overturn their preconceived notions of what it means to be a citizen.

How? If you live in the United States and are not a Native American (whose ancestors were already in North America when the first European settlers arrived) or an African American (whose ancestors were brought to the US by force), you are the descendant of an immigrant — and chances are you haven’t thought enough about what American citizenship means, says Jose Antonio Vargas. “What most people don’t understand about immigration is what they don’t understand about themselves — their family’s old migration stories and the processes they had to go through before green cards and walls even existed, or what shaped their understanding of citizenship itself,” he says. By asking yourself three questions — “Where did you come from?” “How did you get here?” and “Who paid?” — Vargas believes that people can come to realize that citizenship doesn’t mean simply being accepted into a society by an accident of birth or a rule of law; it also means participating in and contributing to a community, and educating others. And it demands that we become something greater than ourselves: citizens who are ultimately responsible to each other.

Abena Koomson-Davis performs “People Get Ready” and “Love’s in Need of Love” at TED2020: Uncharted on July 9, 2020. (Photo courtesy of TED)

Performer, educator and wordsmith Abena Koomson Davis keeps the session moving with performances of “People Get Ready” and “Love’s in Need of Love.”

“Let this be our moment to move forward with the fierce urgency of a new generation, fortified with our most profound and collective wisdom,” says Jacqueline Novogratz, founder and CEO of Acumen. She speaks at TED2020: Uncharted on July 9, 2020. (Photo courtesy of TED)

Jacqueline Novogratz, founder and CEO of Acumen

Big idea: We must start the hard, long work of moral revolution, putting our shared humanity and the sustainability of the earth at the center of our systems and prioritizing the collective instead of the individual.

How? Our problems are interdependent and entangled. To fix them, we need more than a systems shift — we need a mindshift, says Jacqueline Novogratz. Pulling from her storied career empowering people in underdeveloped communities worldwide, she shares some of the wisdom and knowledge she’s earned in transforming her own unbridled optimism into hard-edged hope and lasting change. For humanity to spark its own moral revolution, we need an entirely new set of operating principles, of which she offers three to start: moral imagination, in seeing people equal to ourselves, neither idealizing or victimizing; holding opposing values in tension, with leaders cultivating trust by making important decisions in service of others, not themselves; and accompaniment, encouraging others to join in and walk along the side of morality. This work may seem tough, but Novogratz reminds us that we don’t change in the easy times, we change in the difficult times. Discomfort can be seen as a proxy for progress. “Let this be our moment to move forward with the fierce urgency of a new generation, fortified with our most profound and collective wisdom” she says. “And ask yourself: What can you do with the rest of today, and the rest of your life, to give back to the world more than you take?”

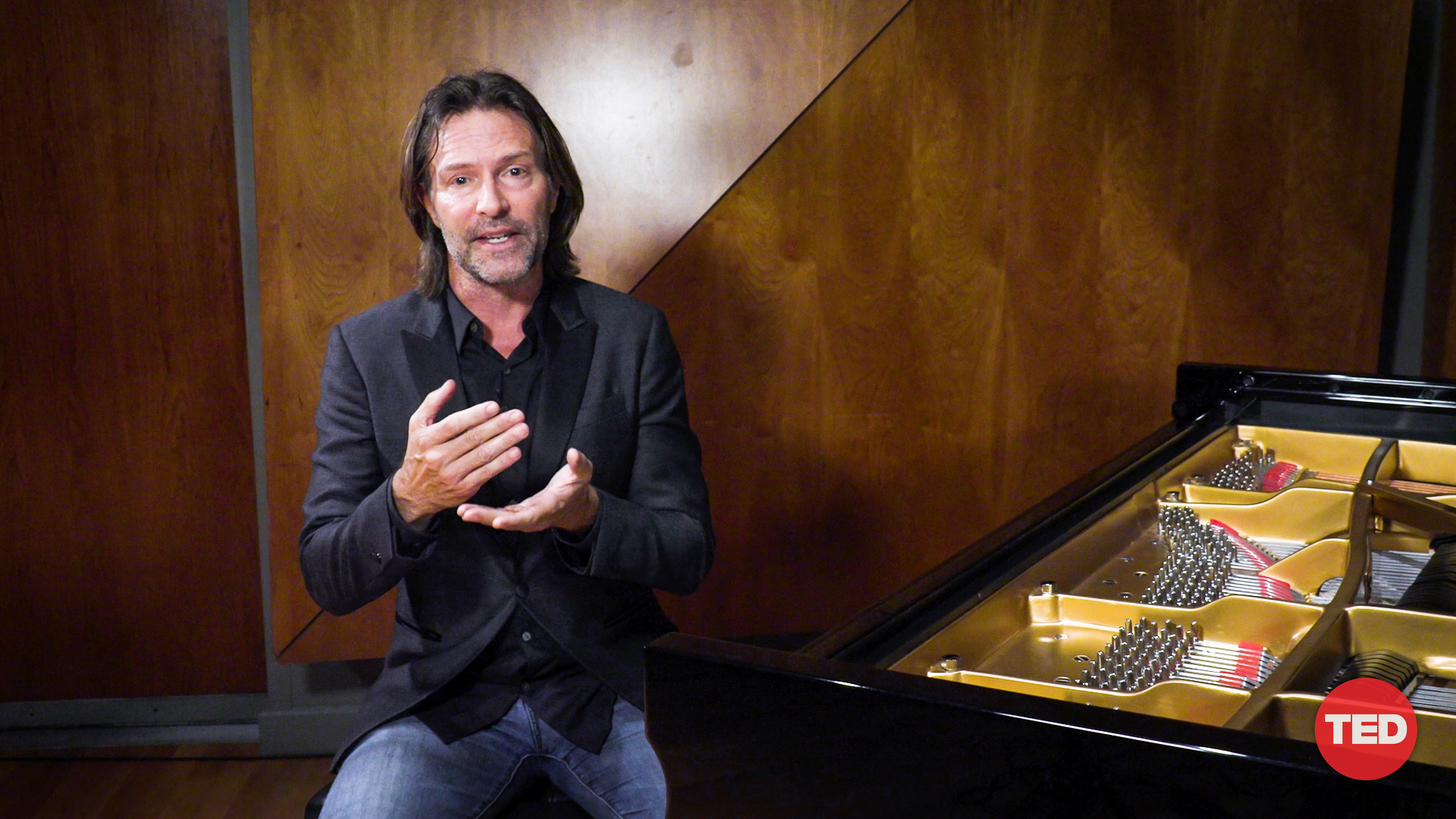

Eric Whitacre introduces “Sing Gently,” an original composition performed by a virtual choir made up of singers from across the globe. He speaks at TED2020: Uncharted on July 9, 2020. (Photo courtesy of TED)

Eric Whitacre, composer and conductor

Big idea: A virtual choir — representing 17,572 singers across 129 countries — can show us how connected we all still are.

How? When the COVID-19 crisis hit, Whitacre felt compelled to create a virtual choir. (Check out his epic performance from TED2013 to hear what that sounds like.) He wanted to make a kind of music to help the world heal, to encourage a gentle way of living with each other. So he composed “Sing Gently,” a piece inspired by the Japanese art form kintsugi — the art of repairing broken pottery with gilded epoxies, thereby illuminating the pottery’s “wounds,” as opposed to hiding them. Whitacre hopes that his staggeringly large virtual choir, spliced together with contributions of singers across the globe, will have the same kind of effect on our torn social fabric. “When we are through all of this, we will be stronger and more beautiful because of it,” he says.

“I truly feel that if all of us took care of the earth as a practice, as a culture, none of us would have to be full-time climate activists,” says Xiye Bastida. She speaks at TED2020: Uncharted on July 9, 2020. (Photo courtesy of TED)

Xiye Bastida, climate activist

Big idea: Humanity needs to cultivate the heart and courage to love the world.

How? In a letter to her abuela, Xiye Bastida reflects on being a leading voice of youth climate activism and Indigenous and immigrant visibility. Bastida’s days are occupied with mobilizing masses in New York City to join the climate movement, joining Greta Thunberg’s global climate strike and becoming fluent in climate science (all while sacrificing the normal activities of a teenager). “I do this work because you showed me that resilience, love and knowledge are enough to make a difference,” she writes to her abuela. Bastida shows us that, with unwavering commitment rooted in love, we are capable of igniting far more than we can imagine. “People make it so easy for me to talk to them, but they make it so hard for me to teach them,” Bastida says. “I want them to have the confidence to always do their best. I want them to have the heart and the courage to love the world.”