You express yourself through nearly every artistic medium – painting, performance, writing, film. What drives you to make art?

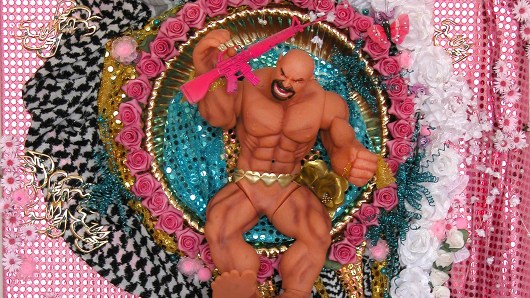

Most of my work is reactionary to where I live. And where I live now, Beirut, is one of the most volatile places in the world. Through my work, I am trying to create bridges between cultures and religions. My work is a by-product of political and economic turmoil, focusing on issues of violence, gender and religion and their place in our bubblegum culture. I try to expose the superficiality of war, creating an alternate reality. My weapons of choice are love and humor. The need to create justice through art is deeply rooted in my childhood, and I know I have consciously chosen to live in a place where my work is necessary. But I have also learned that anger is the worst tool, and violence begets violence.

It is easy to assume certain things about my work when you see all the glitter and beads. But I found that in order to paint or write about violence, I had to create my own language and my own visual vocabulary. I think that there is a big difference between popular culture and kitsch. Popular culture is an international language. It builds bridges and brings people together. It can destroy stereotypes if used in the right way. And it can promote peace because it’s so accessible. I strongly believe that my work should speak a language that people know how to use. Peace should be completely accessible.

I don’t use glue in my work, I use tiny pins — thousands of them! I have developed a type of canvas where everything is stuck in with pins. In a way, it reflects the instability of my region. It is also a reflection of a huge problem we have in Lebanon that some have labeled as collective amnesia — we try too hard to forget our wars too quickly, our history is constantly being rewritten to suit different political and religious ideologies. At any point in time, one could completely rearrange my paintings to tell a different story.

The physical process of using pins puts me into a state of meditation — this act of repetition creates an environment of peace around me. While I’m in my studio, I don’t worry about bombs dropping. You see: glitter reflects light. And the more color and glitter I use, the closer I am to the light — to the source. The pink objects and embellishments are my positive energy. I take aim and shoot them into the heart of fear to negate the negative.

You are Lebanese but have lived all over the world. What was your path to Beirut?

I was born in London but spent the first 15 years of my life in Lagos, where my family had emigrated. It was an incredible experience, but it forced me to grow up very quickly. I was very aware of what I had and what others didn’t have. On the drive to school every morning, I saw faces and situations that broke my heart. I became very angry at the way the world works, with our differences. I was angry about being Lebanese. I was angry about being a girl. I was angry about feeling like there was nothing I could do to change the situation.

Then I discovered student council and ran for secretary in 5th grade. I made only one poster, drawn by hand, and lost. The poster, however, was pretty good, and I realized that I could draw. I started copying album art of heavy metal bands, and kept getting better. In the 6th grade, I ran for class president and won. But this time it was because I rode a horse into school with a big “Vote for Zena” sign. I think that was my first site-specific installation attempt.

By the time I was done with school in Lagos, I understood there were two things that I loved more than anything: art and politics. I moved to the UK for boarding school and continued to win school elections with really cool poster campaigns. Unfortunately, my high school principal was racist and had a deep dislike of Arabs. In my senior year of high school, when I was school president, he still managed to suspend me and prohibited me from speaking at the graduation ceremony. I was really disappointed, because even though I’d presented myself as a rebel rouser, like any teenage kid, I just wanted to be accepted. With that thought in mind, I decided to move to Lebanon where maybe I would find other people like me. Maybe I would find home.

So you were in Beirut during the Israeli invasion of 2006, which gave birth to your blog, Beirut Update.

The first night the bombs started falling, I really thought I was going to die. And I wanted to make sure the whole world knew exactly how and why. The media were very slow to report on what was going on and I thought I could do my part, or at least tell my own story. I wrote all through the night, and in the morning I sent the email to every person in my address book, even people I hadn’t spoken to in years. I managed to sleep for a few hours, and when I woke up, my inbox was flooded. So many people wrote back asking how they could help.

A day later the UK Guardian got in touch, asking if they could reprint my first three emails. I agreed and they gave me the whole G2 supplement, and soon after syndicated the emails. My letters had gone global. Then a friend helped me set up a blog so people could reach my work more easily. I had no idea then how important blogging was to become for the Arab world.

I saw that the more transparent and human I was, the more audience I reached. It was the first time in my life I was so afraid, but in that month, I learned that love was the most powerful weapon. It was almost a self-defense mechanism: love would keep me alive. And just like Scheherazade, I believed that writing every day would bring me a new day. I wrote about life under the bombs, about the environmental disasters caused by the war, and about my best friend, Maya, who had recently been diagnosed with cancer. I thought that if people read about Maya’s condition, it could encourage them to call their governments and demand a ceasefire.

I stopped blogging the day the invasion ended. It was a war diary and I wanted it to stay that way — a testament to what had happened. I saw it as a painting, and it was pretty much complete. I only went back to post an article after Maya passed away. A lot of people became very connected to her through my writing, and I knew I had to share the sad news with them. A month later, a friend of mine was almost killed in the West Bank during an Israeli raid. I posted her letter, but then knew it was time to stop. There were always going to be moments like that, and I really wanted the blog to be what it was and nothing more. The painting was now complete.

You also happened to be in New York during 9/11. Tell us about xanadu*, your response to the event.

I lived in NYC from 2000 to 2004. Watching the first tower fall, I knew my life and the world would never be the same again. I knew the repercussions were going to be long and disastrous. It was not easy being an Arab in New York after that. I wanted to find a way to give back and stop the anti-Arab sentiments, which were spiraling out of control. My friend Imad Khachan and I started a nonprofit gallery space just off Washington Square Park that focused on exhibiting the work of Arab artists living in New York. I thought this would be a way to break stereotypes and overcome fear and suspicion. I also exhibited local artists, and we built a community of artists, writers and musicians with monthly exhibitions, readings and performances.

Now xanadu* is based in Beirut. I have shifted its focus to supporting young writers, especially helping poets get their first books published. I have also published the first few editions of a local comic book magazine. The idea behind xanadu* is to provide young or underrepresented artists, writers and musicians with a platform to leap off of: the first exhibition, first performance or first publication, whatever is needed to help creative people fly.

I strongly believe that our region can change for the better. And I believe that education, art and literature can help bring about positive changes. I know this from myself — if I hadn’t jumped into all that drawing and dancing (some call it head-banging), I could have gotten myself into a lot more trouble. I think I was very lucky to have been able to travel and receive the education I did. This is my way of giving back. I love working alone in the studio, but I also love being with a growing community. One of the greatest joys I experience is handing over a book, hot off the press, to the poet.

What are you up to now?

After Maya passed away, I went through a very difficult period and stopped painting. I pretty much gave up on life, and also went through a divorce. All in one year. But one night I had a beautiful dream. Maya had come back. I woke up not knowing where I was, the dream was so real. I started writing the dream and kept writing, and things developed. Two years later, my book, Beirut, I Love You was born. A wonderful woman, Samar Hammam, had found me during the war and convinced me that I had to write a book — a book that wasn’t the blog. She became my agent and got it published into several languages, and then I spent a year traveling to festivals to talk about it. At some point, my travels landed me in Italy, and that’s where I met Gigi Roccati and fell in love. The universe can be so generous, and life had given me a second chance.

Gigi, being a director, convinced me that we had to make a feature film based on my book. I accepted and we began a grueling two-year process of adapting it into a screenplay. We now have some incredible producers on board and will be filming soon. I am going to be making original artwork for the film too.

Another ongoing body of work I’m working on is Goods for Gaza. There is a blockade on Gaza by the Israeli army via land, air and sea. In 2010, a group of activists tried to sail into Gaza carrying much needed supplies and aid for the people. One of the ships, the Mavi Marmara, was boarded by Israeli commandos and some activists were killed. The army claimed the boats were a threat, bringing in weapons. I was curious. What exactly is this blockade all about, and what are the items banned from Gaza? What items caused the death of these activists? I did a simple online search and found the list. It contains about 2,000 items, which includes the following: desks, donkeys, A4 paper, biscuits, goats and ginger. I have been making a mixed media painting for each word, and will continue to do so until the blockade ends. Palestinian children should have the right to eat chocolate.

And you have a book coming out!

Yes, Beirut, I Love You is finally coming out in the States on October 16, published by The New York Review of Books. We’ve planned fun events that include slide shows, short film screening and a tap-dancing performance by the spectacular TED Fellow, Andrew Nemr. On October 18, I’ll be at Busboys & Poets in DC.

Last but not least, this November will be the 10-year anniversary of my ongoing Pink Bride of Peace project. I wear a big pink wedding dress and run around the streets of Beirut during the yearly Beirut International Marathon in an attempt to spread peace and love. I have passed out flowers to hundreds of people over the past years — and even some kisses every now and then. Honestly, I don’t know if it’s working, but I do know that I’m trying my best. And the fact that I can still fit into that same dress after 10 years — well, it’s a great sign!

Why do you use pink so prominently in your work?

Pink is like cotton candy. It’s fluffy and sweet. Too much of it, though, will leave a bad pain in your stomach. It’s quick and superficial. Barbie, GI Joe politics, and Cherry Cola to me represent a generation completely embedded in consumer culture. We are the pink generation. But it is also the color of nonviolent protest. I convert objects of violence into a celebration of life through a transformation into something beautiful. It’s like the plastic I use in my paintings, which is made from oil — the same oil mankind is at war for.

What’s your experience of being a TED Fellow been like?

It’s amazing so far. And I feel that it’s something that will keep getting better as I learn how to navigate through this incredible opportunity. As an artist, I’m used to working long hours alone, never asking for help. One of the best parts about being a Fellow is the incredible coaching sessions you get. It has helped me tremendously — artists are shy to talk about their work. TED is helping me gain the confidence I need!

But even more than that are the other Fellows. I sometimes felt like I was the only person in the whole universe who thinks and feels things to a certain depth. And then when I walked into the first meeting at the lobby in Long Beach, I was blown away and also very humbled. I feel like I’m gaining a new and beautiful family who understand me without me having to say a word. They give me the courage I need to keep going forward. I know I will never feel alone again. This is truly a humbling experience and I feel so lucky to be part of it!

Comments (6)

Pingback: ISIS, the World Cup and everything in between: a letter from Beirut | TEDFellows Blog

Pingback: Zena el Khalil builds peace from the rubble of homes lost to war | TEDFellows Blog

Pingback: The house is a witness: A TED Fellow makes art from the rubble of her homes lost to war | BizBox B2B Social Site

Pingback: The house is a witness: A TED Fellow makes art from the rubble of her homes lost to war - Rixal Communications | Custom Media & Advertising | Media. Solved. | Rixal.com

Pingback: Zena El Khalil: Beirut’s pink bride under the black sky. | middle east revised

Pingback: TED Global newsmakers: A closer look at Laptop U, plus the first all-female race in Beirut, and more | Krantenkoppen Tech