Aloe Blacc performs songs “to tell the stories of the underdog.” Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

It is hard to believe that this is final session of TED2015. Luckily Session 12, “Endgame,” is our longest ever — with two full hours of talks that took us on a journey through the human experience, from anger to laughter and back again. Read a recap of these inspiring talks.

An ode to anger. Kailash Satyarthi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize along with Malala Yousafzai in 2014. But he’s not here to talk about world peace. “Today, I’m going to talk about anger,” he says. Satyarthi felt anger as a child seeing the ravages of inequality; at age 27, talking to a father whose daughter was about to be sold to a brothel; at age 35, locked in a prison cell; and at age 50, lying in a pool of blood in the street with his son. “For centuries, we were taught that anger is bad. Our parents teachers, priests, everyone taught us how to control and suppress our anger,” he says. “But I ask: can’t we convert our anger for the larger good of society?” Satyarthi’s anger became an idea — a consumer campaign to create demand for child-labor free products — and then action that resulted in an 80% decrease in child labor in South Asian countries, he says. And later it led, to raid and rescue campaigns. “I am so lucky and proud to say that not 1, 10, 20 — my colleagues and I have liberated 83,000 children and handed them back to their mother.” In the last 15 years, the number of child laborers has gone down by a third, says Satyarthi. “Anger has a power and energy,” he says. Read much more about his talk.

Stories of the underdog. Grammy-nominated musician Aloe Blacc stepped on stage, hands peacefully at his sides, and looked out with clear, full eyes. A cappella, his low, resonate voice sang the hopeful yearnings of a child in need, “I don’t want to die young because I feel my life has just begun … I don’t want to die in vain.” In between songs, he shared how after a life in the corporate world, he pursued music in order to create positive social change and “tell the stories of the underdog.” Next came “The Man,” a song about taking your place in the world, despite making mistakes in the past. He closed with a stripped down, acoustic version his hit, “Wake Me Up.” This brought both the TED and TEDActive crowds to their feet, as they danced and clapped along.

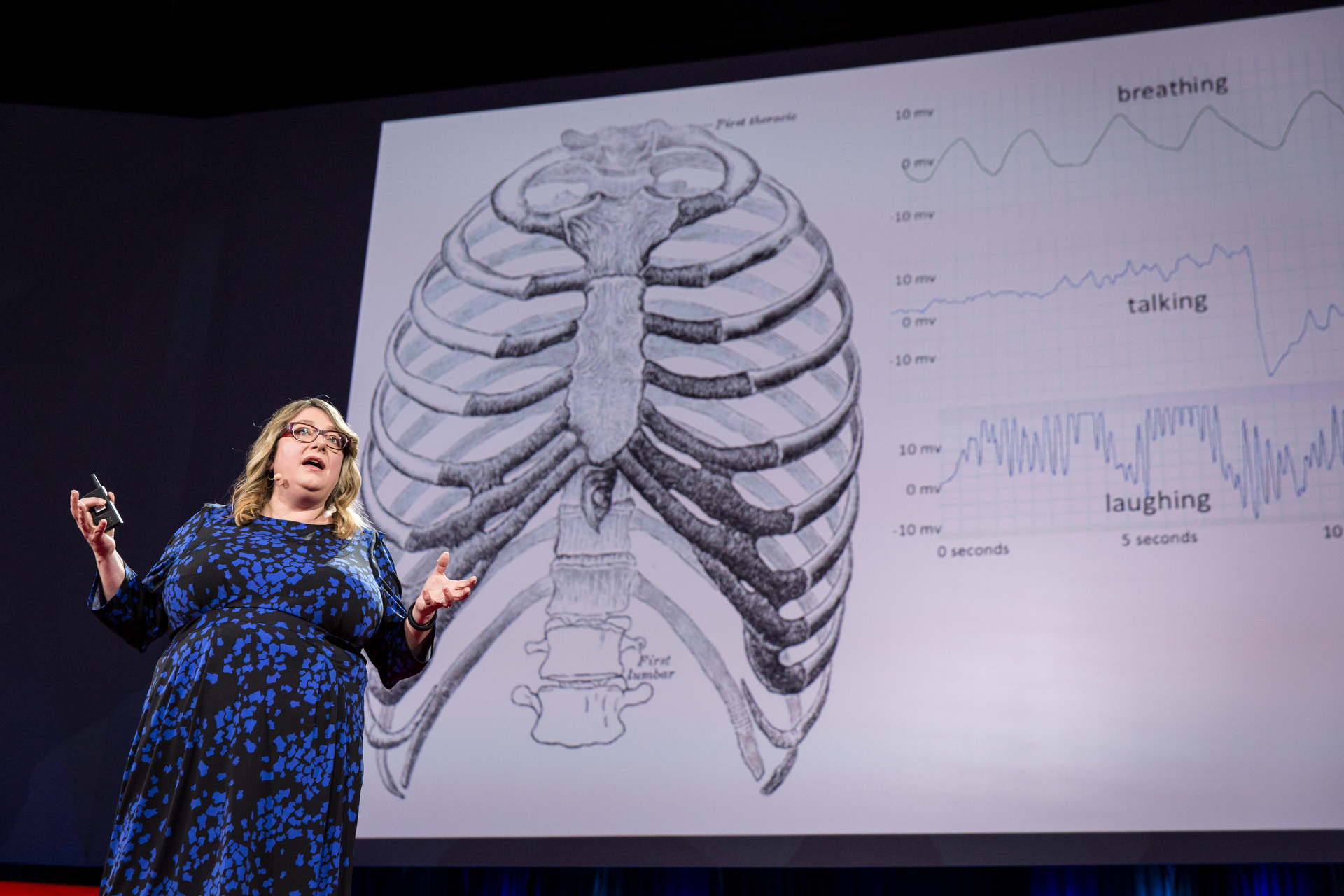

Why we laugh. “I’m going to play you some sounds of laughter,” says neuroscientist Sophie Scott. “Consider what a very strange noise it is. Notice how primitive laughter is — it’s much more like an animal call than speech.” Laughter, she explains, is associated with interactions. “You’re 30 times more likely to laugh if you’re with someone else than if you’re on your own,” she says, pointing out that laughter is behaviorally contagious. “And you’re more likely to laugh if know someone.” In other words, laughter does social work for us. Scott is researching two types of laughter: real, uproarious involuntary laughter and polite social laughter. “Turns out that people are phenomenally nuanced in terms of how we use laughter,” says Scott. She shares a study done by Robert Levenson in which married couples are put in a stressful situation. “What he finds is that the couples who manage that feeling of stress with positive emotions like laughter immediately become less stressed,” he says. “They are also the couples that report high levels of satisfaction in their relationships and they stay together for longer.” And it doesn’t just modulate relationships, it helps us deal with embarrassment and simply makes us feel better, too.

Sophie Scotte explains laughter: real, fake, where it comes from at what it means. Click the image to watch this talk. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

How the global economy is like a boat. Dame Ellen MacArthur remembers stepping on a boat for the first time. “I will never forget the feeling of adventure,” she says. At 17, she left school to sail, and four years later — in 1997 — she designed a boat to sail solo nonstop around the world in the Mini Transat transatlantic race. She came in second. But she wanted to do something even more bold: to break the world record for the fastest solo circumnavigation. As she was about to set off, another sailor completed the journey, taking the record from 93 to 72 days. MacArthur went forth anyway, on a trek through oceans so vast that the nearest people to her were those manning the European Space Station above. “We know what it’s like driving a car, 20, 30, 40 mph,” says MacArthur. “At 100 mph, you have white knuckles. But remove road, remove the windshield wipers, remove the windscreen, remove the headlights, remove the brakes. That’s what it’s like in the southern ocean.” But MacArthur succeeded. “As I stepped off the boat at the finishing line, having broken record, suddenly I connected the dots,” she says. She realized that the world is like her boat — remarkably finite. She made the unconventional decision to leave sailing behind and focus on the global economy. “The framework within which we live is fundamentally flawed,” she says. “We take material out of ground, make something out of it, ultimately that product gets thrown away … It’s an economy that fundamentally can’t run in the longterm.” In 2010, she founded the Ellen MacArthur Foundation to work on how to create a circular economy, one that plans for reuse from the very beginning. The foundation works with universities, businesses and governments to make this happen.

A message of hope. Curator Chris Anderson reveals an exclusive video conversation between him and His Holiness the Dalai Lama, filmed late last year. In their talk, the Dalai Lama speaks about two kinds of happiness, how all humans can coexist, and the cooperation between science and Buddhism. He has a happy message: “Our very existence is very much based on hope.”

BJ Miller urges us to rethink death so we can best live life. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Rethink death with design-thinking. In college, a train accident nearly took BJ Miller’s life. 11,000 volts later, this near-death experience gave him a new outlook on how to live life with the eventual certainty of death. As a physician and palliative caregiver at the Zen Hospice Project, he explained to the TED audience why we need to bring design thinking to how we care for the dying. We need to make care patient-centered, not disease-centered. To do this, we first must accept that for most people, the scariest thing about death isn’t being dead, but the suffering of dying. This distinction between necessary and unnecessary suffering can allow care to become a more generative act. At the same time, concentrating on the aesthetic realm can help elevate patients experiences. “One of the most tried and true interventions is just to bake cookies,” he says. “As long as we have our senses, even just one, we have the possibility of accessing what makes us feel human and connected.” If we commit ourselves to designing toward death in a thoughtful way — accepting its inevitability but not being limited by it — we realize, “that you can always find a shock of beauty in what you have left.”

Baby coral and Bill Gates: A week in review. “In the history of comedy no one has had to follow ‘redesigning death,’” says the very funny Baratunde Thurston in the annual conference wrap-up. After ninety presenters, twenty hours of main stage presentations, and five pounds of vegan snack foods per sitting, Thurston gives us a final run down of the scary, amazing, baller talks from the preceding days. “Only at TED,” he jokes, you’ll hear, “You all saw the Economist cover a few weeks ago,” “for those of you who are zoning junkies,” “Bill Gates is going to be available to meet you at the Ebola room,” and massive applause for a photo of baby coral.

Baratunde Thurston looks back at previous talks in his funny final rundown of TED2015. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Kate Torgovnick May and Cynthia Betubiza contributed to this post.

Comments (10)