Diane Wolk-Rogers is a teacher at Parkland, site of a horrific massacre two months ago. She asks us to engage with the issue of gun violence — to keep such a mass school killing from ever happening again. And, she says, “If you’re not sure where to start, look to my students as role models.” Wolk-Rogers speaks at TED2018 on April 10, 2018, in Vancouver. Photo: Ryan Lash / TED

Let it be noted, says co-host Chris Anderson, that this year’s TED started with a roaring cheer and with a scream of anguish. Our job this week is to explore what’s amazing, in every sense of the word, from the jaw-droppingly wonderful to the shocking and urgent. So Chris and co-host Helen Walters have decided to kick off Session 1 with a quick voice vote: How do you feel about things these days? They prompt the audience to respond with a happy “yay!” or a scream of “argh!” And it’s about 50/50 between them. Clearly, it’s time for TED.

Embracing lifetimes of fury. We are in the midst of a cultural shift — and that shift is being led by women. Generations of women have dealt with harassment, and generations have been silenced. Women have been told they are overreacting, they are being unreasonable, they are being too sensitive. But actor and activist Tracee Ellis Ross has a message: the global collection of women’s experiences will not be ignored, and women will no longer be held responsible for the behaviors of men. There is a “culture of men helping themselves to women,” from seemingly innocuous slights to the “most egregious, violent and horrific situations.” This culture exists on a spectrum where “the innocuous makes space for the horrific” — and women have to live with the effects of both. Ross believes it is past time that men take responsibility to change men’s bad behavior. She offers an invitation to men, calling them in as allies, with the hope they will “be accountable and self reflective. Compassionate and open,” that they will ask how they can be of service to change and supportive of women. As for women, she offers a different invitation: “acknowledge your fury.” Women have tamped down and rationalized away that fury for centuries, because women aren’t supposed to get angry. That fury is a result of never being able to directly address or express indignation, frustration and rage. It is the result of being ignored and quieted. And it is time to harness it, she says. “Your fury is not something to be afraid of. It holds lifetimes of wisdom. Let it breathe, and listen.”

Tracee Ellis Ross opens the TED2018 conference with a manifesto for women and men. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Use supporting detail. What’s it like to be a teacher in the midst of a school shooting? Humanities teacher Diane Wolk-Rogers begins her talk with a calm, detailed recitation of what happened in her classroom during the massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, two months ago. She lined up her students. She held up a sign so they could follow her. She led them down the hall, away from the pop pop pop of bullets. Outside, she sat on the curb, calling her family to say she was okay. And she knew that her world would never be the same. How to move forward? She calls on the same techniques she uses in her classroom: to admit when she doesn’t know the answer, do some research, and start coming up with options. We start with the history of the Second Amendment. Ratified in order to build a militia to protect a fledgling nation, it’s been re-interpreted in significant ways throughout the following years. And that gives Wolk-Rogers hope: “The interpretation of the Second Amendment and cultural attitudes about guns have changed over time — which gives me hope they could change again.” She offers three ways we could move forward to create more safety and responsibility around guns. And there’s a fourth option: the solution we can create ourselves.

Jaron Lanier helped to conceptualize our digital culture in its early years; he spoke at some very early TEDs to share this vision (here he is at TED2). He returns to the stage this year to review our progress and make a bold pitch to reclaim our humanity online. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

A vision, a warning — and a way forward. Jaron Lanier steps onstage clearly affected by the talk that came before him. He takes a moment, wipes his eyes, and says to Diane, “Thank you.” A pause, and he begins. We too start in the past, in the early digital culture that Lanier was instrumental in thinking through. But haunting his pioneering vision of an internet built on “post-symbolic communication” — a place where humans share experiences through shared, beautiful interactive worlds — has always been a lurking dark side of control and stratification created by omnipotent personal devices that control our lives, monitoring us and feeding us stimuli. Of course, this dark side is, arguably, exactly the world we’ve built for ourselves today: bots influence elections, truth bows before “truthiness,” and the lowest common denominator sinks lower and lower. How did we get here? Lanier has a theory: It lies in Silicon Valley’s two conflicting desires: to make everything free, while we simultaneously venerate entrepreneurial money-making. If everything is free, where does the money come from? Online advertising. And, as he says, “What started out as advertising really can’t be called advertising any more. It can only be called behavioral modification,” targeted and data-driven and manipulative. These free platforms now use behavior modification to turn people into eternal consumers — a “globally tragic, ridiculous mistake.” As he says: “We cannot have a society in which if two people wish to communicate the only way that can happen is if it’s financed by a third person who wishes to manipulate them.” In this bold talk, Lanier challenges tech companies to look beyond revenue models favoring virality over credibility, and to instead strive for “peak social media” — a place where paid, high-quality content mimics the paid models of “Peak TV” (think HBO, Netflix and Amazon) and steers us toward a future where unbounded creativity, equality and love defines the human race. (Read an excerpt from his newest book here.)

Bringing some New Orleans flair to Vancouver. Live and direct from New Orleans, The Soul Rebels rocked the TED stage with a tight, rhythmic and energetic musical interlude. The eight-piece band, with two trumpet players, two trombones and two percussionists rounded out with a tuba and Sousaphone, played three songs — “Rebelosis,” “Rebel Rock” and “Rebel on That Level” — turning the red circle into a jazz club, if only for a few minutes.

When Zachary Wood invited a controversial speaker to his campus, he got a fascinating lesson in how to listen to voices he disagreed with. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Why we need to be uncomfortable. In 2016, Williams College student Zachary R. Wood wrote to two conservative thinkers whose ideas he despised, Bell Curve coauthor Charles Murray and commentator John Derbyshire — and invited them to come speak on his campus. Wood is the president of Uncomfortable Learning, a college group that specializes in the particular education that comes when we try to understand the “other side.” His upbringing was defined by strong conflicting forces — the volatile mood swings of his mother, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia when he was 10, and also her fierce intellect and sense of empathy. “She encouraged me to see the world and the issues our world faces as complex, controversial and ever-changing,” says Wood. At Williams, however, he found his openness to “difficult ideas” was not shared by the entire student body — the outcry eventually led the college president to rescind Derbyshire’s invitation. “Yet tuning out opposing viewpoints doesn’t make them go away,” contends Wood, now a senior. “In order to understand the potential of society to progress forward, we need to understand the counter forces.” His parting wish: to live in a world with leaders who are “familiar with the depths of the views of those they deeply disagree with so they can understand the nuances of everyone they’re representing.” Washington, are you listening?

Why science must be free. Fake news, alternative facts, and other forms of suppression are affecting all types of scientific issues, including climate change – and that’s a big problem. “In our modern, technological age, when our very survival depends on discovery, innovation and science, it is absolutely critical that our scientists are free to undertake their work, free to collaborate with other scientists, free to speak to the media, and free to speak to the public,” says Kirsty Duncan, Canada’s first Minister of Science. What’s more, they must be able to explore controversial and unconventional topics, present uncomfortable truths, challenge the thinking of the day, and to fail. “That’s how scientists push boundaries and pushing boundaries is, after all, what science is all about,” she says. As Science Minister and former parliamentary member, Duncan has worked hard to make this a reality in Canada, where scientists like Max Bothwell were previously prevented from speaking freely to the media. “If you see that science is being stifled, suppressed or attacked, speak up. If you see that scientists are being silenced, speak up. We must hold our leaders to account,” she says. “After all, science is for everyone, and it will lead to a better, brighter, bolder future for us all.”

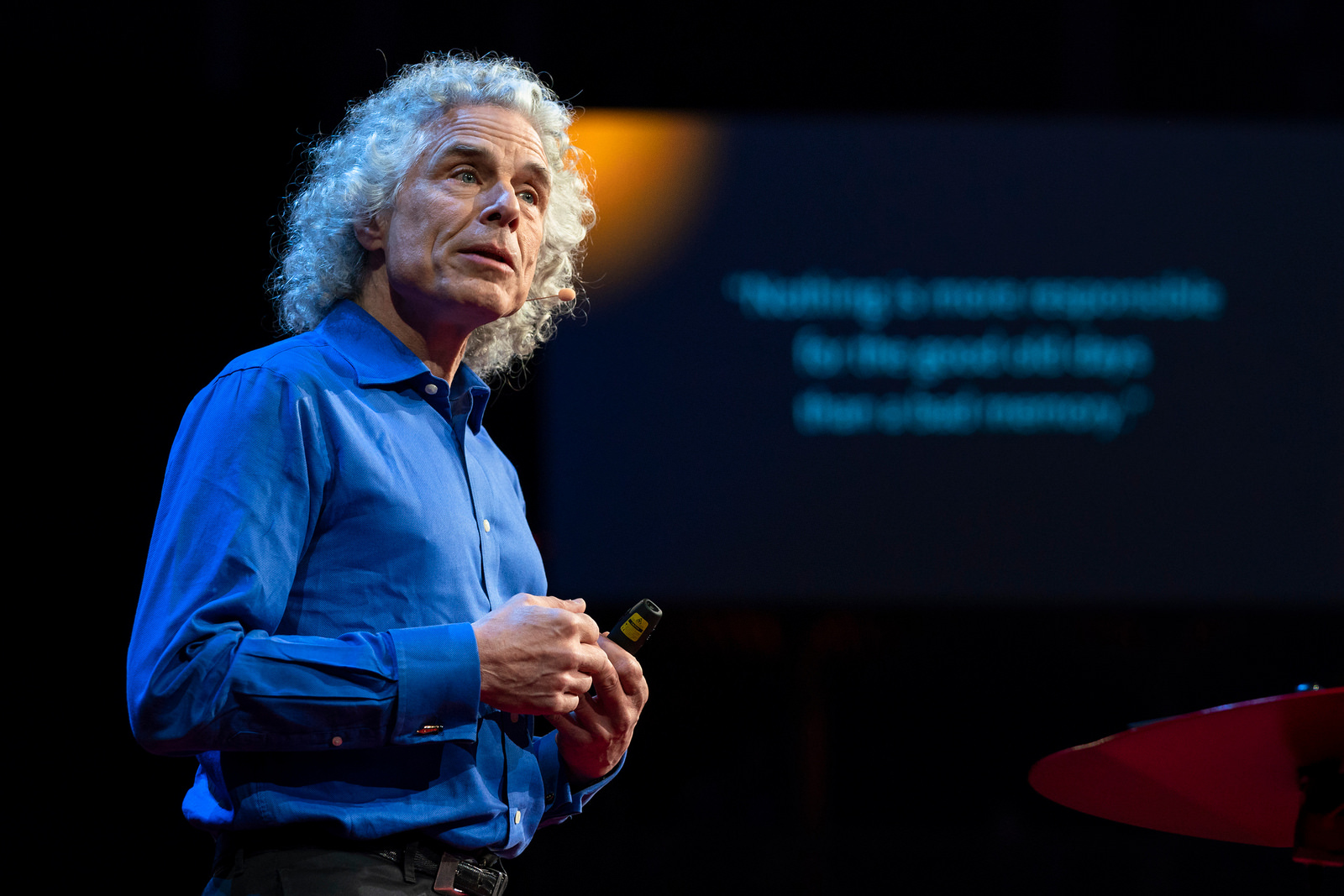

“Is progress inevitable? Of course not. Progress does not mean that everything becomes better for everyone everywhere all the time. That would be a miracle, and progress is not a miracle, but problem solving.” Steven Pinker muses on the idea of progress onstage at TED2018. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Has the world (for all its troubles) gotten better over time? Every day, we read about shootings, inequality, pollution, dictatorships, war and the spread of nuclear weapons. These are some of the reasons that 2016 was called the “worst year ever” — until 2017 claimed that record and left many longing for earlier decades when the world seemed safer, cleaner and more equal. “Is this a sensible way to understand the human condition in the 21st century?” asks psychologist Steven Pinker. Comparing the most recent data on homicide, poverty and pollution with the same measures from 30 years ago, Pinker shows that we’re doing better now in every one of them. The same goes for autocracies, nuclear weapons and deaths from terrorism, all of which are on the decline when compared with 1988. So why do people still think the world is going to hell? Pinker thinks it has something to do with progress — specifically, an aversion to the idea of it, even by progressives. Progress isn’t a matter of faith or optimism of seeing the glass half full, Pinker says; it’s a testable hypothesis. But while humanity has become more democratic, safer, happier and more peaceful (not to mention more likely to know how to read and write and have access to running water and technology), you wouldn’t know it by looking at the news. The New York Times has gotten increasingly morose, and a sample of the world’s broadcasts have gotten steadily more glum, Pinker says, because of our cognitive bias to focus on the bad and not the good — and because news is about what happens, not what doesn’t happen. (You never hear a journalist say they’re reporting live from a country that’s been at peace for 40 years or a city that hasn’t been attacked by terrorists today.) Progress isn’t inevitable; it doesn’t mean everything gets better for everyone, everywhere, all the time; and it’s not a miracle, he says. Instead, it’s problem-solving, and we should look at climate change and nuclear war as problems to be solved, not apocalypses in waiting. “We’ll never have a perfect world, and it’d be dangerous to seek one,” Pinker says. “But there’s no limit to the betterments we can attain if we continue to apply knowledge to enhance human flourishing.” (Read an excerpt from his newest book here.)