Physician and anthropologist Paul Farmer, who co-founded Partners in Health, comments on the new TED Book, “The Upstream Doctors.”

By Paul Farmer

At the end of almost a decade spent in teaching hospitals and clinics, most (we hope all) physicians have honed their clinical acumen by focusing on the care of the patient who is right in front of them. Perhaps this is as it should be: as patients, we don’t want our doctors (or nurses or social workers) distracted by “outside” considerations such as the suffering or concerns of other patients not there in the exam room or, heaven forfend, by abstractions such as the extra-personal social forces that place people in harm’s way. We want the doctor focused on us, by bringing expertise and attention to our specific “illness episode” and even to our minor aches and pains. That’s what we want: laser-like focus, to use another term from the medical profession, on our own “chief complaint.”

Or do we? What if most of our aches and pains and many of our serious ailments come largely from those outside forces and abstractions? What if we want to prevent disease or complications of it by altering our risk of poor outcomes (not just death, but predictable or unforeseen complications of the chronic conditions and growing infirmity that most of us will one day endure)? What if we acknowledge that we live not only in bodies but in families, homes (mostly), neighborhoods, and cities? What if our lives outside of the clinic or hospital are often difficult and even, for some people and at some times, almost unendurable? What if our clinical diagnoses are not our chief complaints?

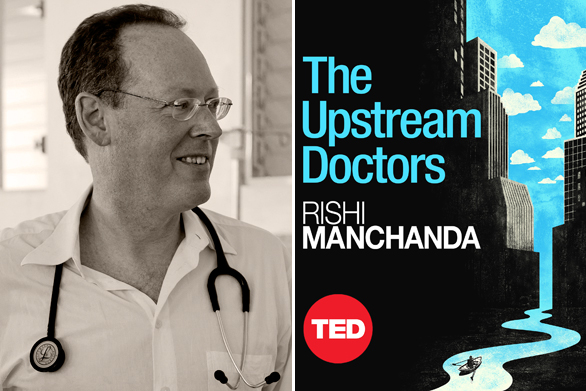

1. The Upstream Doctors, by Rishi Manchanda

Dr. Rishi Manchanda’s TED Book addresses all of these questions with clarity and vision and humility. His vision is informed by long experience, illuminated by the experience of his patients, and solidly buttressed by a great deal of data. The book’s title is borrowed from a well-known parable. Three friends come upon a terrifying scene: as a broad and swift river approaches a waterfall, they see floundering children being swept by in the current, heading towards the cataract. The three friends do the right thing: they jump in and save the drowning children. But the rescuers’ horror is compounded when more kids keep coming down the river. Finally, one of the three starts swimming away from the struggling children. Over the objections of her fellow Samaritans, panicked as they continue their heroic rescues, she swims upstream “to figure out what or who is throwing these kids in the water.”

It’s not that Manchanda is arguing in these pages that we don’t need to save all those already swept into perilous waters. It’s rather, he argues, that we need to divert some of our attention and resources—perhaps more than a third of them—to addressing the root causes of that peril. In other words, we need our physicians to be technically competent, excellent listeners, and able to understand pathogenesis—especially when sickness is not caused, or caused solely, by a microbe or an accident or a readily identified genetic mutation. Make no mistake: Most sickness in this world, whether in South Central Los Angeles or in my workplaces of Boston and rural Haiti, is caused not by a single event or pathological process but by many of them in concert. And most of these causes are to be found far upstream of the etiologies we are taught to seek in medical school and in teaching hospitals.

Effective care for most illness requires understanding the social conditions of one’s patients.

These “causes of the causes” are largely social and environmental ones, as laid out in the clear prose of Dr. Manchanda’s book. Even when etiology is more downstream, effective care for most illness requires understanding the social conditions of one’s patients. Take, for example, the case of Veronica, one of his patients from South Central Los Angeles. In clinical parlance and practice, the story would go something like this: Veronica, 33 years old, presented with recurrent and worsening headaches; these were accompanied by fatigue and malaise. The headaches interfered with her “activities of daily living.” She sought care for her symptoms in an emergency room, where she was “worked-up” for recurrent headache, given medication for pain, and told to return if she did not get better. She returned twice, still in pain, and subsequent work-up included a CT scan, routine blood tests, and a lumbar puncture. These revealed nothing. One doctor, we learn, suggested that Veronica “was exaggerating her pain simply to get narcotics.” The emergency room staff, probably frustrated, referred her back to a primary-care doctor, which is where she started in the first place. Still her headaches persisted, she took more sick days, and felt she wasn’t doing enough for her young children; she worried, in fact, about losing her job. One of these three ER visits alone cost more than her monthly rent.

When Veronica came to his clinic, an “upstreamist” approach led Dr. Manchanda and his colleagues to do a different kind of diagnostic work-up and to propose a different kind of treatment plan. With little probing, Veronica, still in pain and by now exasperated, allowed that she lived in an apartment that was damp, infested by roaches, and full of mold; she couldn’t afford to move and the landlord wasn’t about to repair the leaky plumbing of her small, ground-floor apartment. The diagnosis, Manchanda thought, was migraine headache triggered by chronic allergies and complicated by sinus congestion. Allergens in the damp apartment probably also accounted for her son’s frightening asthma flares, another source of anxiety for Veronica.

Decreased costs and better outcomes for all concerned: if that’s not a formula for value, I don’t know what is.

So far so good: any competent physician or nurse ought to be able to make the diagnosis. Most could do so without advanced medical training; many mothers could, certainly. But the upstreamist approach is not merely to inquire about the causes of the causes; it also calls for addressing them. The clinic in which Dr. Manchanda practiced as an upstreamist works with community health workers and tenants’ rights groups which, in essence, extend the clinic right into their patients’ homes (if they have them) and lives. The medical staff connected Veronica to a community health worker, who could visit her at home and help make sure she was able to obtain and take the medications likely to give her short-term relief from her symptoms. That’s one of the things that community health workers do—or would do if only we had enough of them around. As for her housing conditions, another partnership came into play: a tenants’ rights advocacy group, long active in Veronica’s neighborhood, petitioned the landlord—this time with a doctor’s note in hand—to make the improvements that were always part of his contractual agreements and were in keeping with local building codes. Veronica got better, as did her son. She also stopped using the emergency room for primary care; from then on, most of her care occurred right in her home or in a nearby clinic termed a “patient-centered home.”

It’s not that Dr. Manchanda and his colleagues were not involved in her ongoing care but rather that, in an upstreamist vision, Dr. Manchanda’s colleagues necessarily include community health workers and advocacy groups and citizens concerned to promote healthy neighborhoods. This approach works with, not on, patients. Together, Veronica and her new partners in care, from clinic staff to community health workers and other advocates, improved the quality of that care, increased the effectiveness of her physician, and lessened her utilization of high-cost but ultimately ineffective, for her, emergency services. Working together, this team also improved the quality of Veronica’s housing, lessened her son’s affliction, and thereby broke a vicious cycle all physicians see far too often: study after study, in city after city, has shown us that it is very expensive to give mediocre medical care to poor or near-poor people living in a rich country. One might even argue that this upstream approach improved the quality of her doctor’s life, too.

Decreased costs and better outcomes for all concerned: if that’s not a formula for value, I don’t know what is. But a better understanding of efficiency, effectiveness, and value in health care is not the only reason to adopt upstreamist approaches or to read a book about them. Understanding more about the causes of the causes will help make medicine matter, help make it better, in part because it forces us to be better listeners. Bertolt Brecht’s haunting verse, “A Worker’s Speech to a Doctor,” published the better part of a century ago, tells a story all too similar to Veronica’s:

When we come to you

Our rags are torn off us

And you listen all over our naked body.

As to the cause of our illness

One glance at our rags would

Tell you more. It is the same cause that wears out

Our bodies and our clothes.

The pain in our shoulder comes

You say, from the damp; and this is also the reason

For the stain on the wall of our flat.

So tell us:

Where does the damp come from?

It can be argued, and often is, that controlling the dampness and mold in Veronica’s flat is not the job of a physician. But to argue that such understanding of causality is not the job of an effective health care system is wrong-headed for a host of clinical, moral, and economic reasons. Explaining these reasons is the primary task of Manchanda’s book, just as it is the primary task of social medicine and its many component disciplines. Addressing the causes and consequences is the primary task of all practitioners, whether based in hospitals or clinics or communities. Seeing them addressed, upstream and downstream, is very often the primary concern of our patients.

These are not new insights, as Brecht’s poem suggests, but as our nation’s health care costs continue to spiral out of control without leading to the expected and wished-for results—looking at the usual indicators of population health, the United States lags far behind most wealthy countries, even though we spend more than any other—these insights are more urgently needed than ever. In Dr. Manchanda’s words, our current standard of care isn’t working well for those who need it most. It’s not that modern medicine isn’t living up to our hopes for new diagnostic and therapeutic tools, although we could, if his prescriptions were heeded, always use more of those. It’s rather that medicine, as it is now practiced, has sharply defined boundaries. These borders keep us from understanding ill health and from doing our jobs well. All the technological fixes in the world are not going to repair our broken health system, not if helping the Veronicas of our world matter to those who now debate its future.

2. Just who is Rishi Manchanda, and how is he qualified to make this diagnosis and to write such prescriptions?

For one, his experience as a clinician and an activist is both deep and broad. Deep because it takes a long time to train as a physician and longer still to complete training in both internal medicine and pediatrics, as Manchanda was the first to do at the University of California, Los Angeles. His experience is broad not only because he is formally trained in public health, but also because he has studied health disparities and their remediation in Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, and India. Such settings can be the font, as emerging consensus has it, of significant “reverse innovation.” And from South Central LA to the rural reaches of northern India to the cities and towns of southern Africa, Manchanda has learned, again and again, that those who help design health systems need to better understand these upstream determinants of health and ill health.

But it’s one thing to understand and other to act. It’s still another to act in a manner that draws on sound analysis. In other terms, it’s one thing to diagnose an illness and another one to treat it; it’s yet another matter, as Manchanda explains in reflecting on Veronica’s experience, to shoulder real responsibility for treating illness effectively. It’s not as if the many doctors and nurses that she saw, in the emergency room or the clinic, make the wrong diagnosis. It’s our collective practice that is malpractice. Our models of caregiving and care delivery can themselves be altered by more upstreamists’ analysis only if we do as Manchanda does and learn to work with others outside of the hospital, in the neighborhoods in which our patients live, in the schools in which they learn, and in the settings in which they work.

Rishi Manchanda began learning these “delivery” and civics lessons well before he had a string of letters after his name or the clinical credentials he earned at UCLA. It was during early visits to northern India that he first worked with grassroots groups seeking to promote health equity, democratic governance, and social and economic development. When he returned to Boston for medical school and public health training, which he undertook at Tufts University, the young Manchanda also joined the National Health Service Corps and a number of groups promoting health equity. It was shortly thereafter, in 1998, that I was lucky enough to meet him at a clinical conference and to hear of his goal: to lead a life of service as a physician to those too often left behind by medical progress and to see their rights to health care expanded through improving systems and through civic engagement at many levels. It’s gratifying to me, and fortunate for his patients and students and co-workers, that Rishi Manchanda has met these goals and many more.

How much of the problem was due to fractured and inconvenient systems of care? Were the upstream problems really beyond the reach of a coalition of concerned providers?

Dr. Manchanda’s interest in the planet’s poorest and most medically neglected has led him back to southern Africa to help design delivery systems to address AIDS, the leading killer of young adults there. It’s an illness so clearly distributed and worsened by large-scale forces beyond the reach of conventional models of care—labor migration, deep poverty, civil conflict, and jarring inequalities of all sorts, including gender disparities—that any system designed to treat AIDS based solely within the hospital or clinic will fail. That’s a lesson Partners In Health, an NGO seeking to promote health and social justice through both “upstream” and “downstream” efforts, first learned in Haiti and then again in Peru, Mexico, Rwanda, Malawi, and Lesotho. The good news is that we can innovate and change, and we did that by working with community health workers and other partners in each and every one of these settings. These systems innovations can be brought back to the United States. The year I met Rishi Manchanda, I’m proud to say, he was an intern at Partners In Health.

While still a student in Boston, he was lucky enough to work with another upstreamist innovator, Heidi Behforouz. Since, as The Upstream Doctors notes, the pantheon of social medicine doesn’t count as many women as men, I will add that Heidi is another hero of mine: a primary care doctor at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and true “partner in health” in every sense of the term, Heidi and her team have spent years providing care for patients struggling, in the shadow of Boston’s teaching hospitals, not only with AIDS (and other chronic medical conditions) but against poverty and its attendant social disarray. Some are homeless or almost; many are jobless or work in dead-end jobs with few benefits; many don’t speak English or speak it poorly; few have good health insurance; some are “illegal aliens” (surely one of the most bizarre labels we’ve yet cooked up) and some have other problems with the law; some are elderly and frail; most have more than one affliction. In short, these were Rishi Manchanda’s preferred patients.

In the eyes of most of our colleagues, however, these particular patients were “failing medical therapy” for AIDS, which was revolutionized for some by the advent, about 20 years ago, of effective therapy. But in Dr. Behforouz’s view, medical therapy was failing them. Even though most were and are eligible for such therapy through publicly funded programs, they were not adhering to the treatment nor enjoying ready access to many other social services. Was the primary problem the non-compliant patients, or were their upstream problems, from housing instability to running afoul of the law and the other “synergy of plagues” that ran together in their lives, limiting their ability to comply, keep appointments, fill prescriptions, and all the other things we ask of patients. How much of the problem was due to fractured and inconvenient systems of care? Were the upstream problems really beyond the reach of a coalition of concerned providers?

For many of these patients, we learned, the problem was delivery. Dr. Behforouz has shown that by providing regular care and social services with the help of community health workers, as in Haiti and Peru, we could expect patients who are failing (or being failed) to do much better than those receiving “standard” care, which is delivered primarily in clinics and at the time of the providers’ choosing. This is true whether the outcomes followed are clinical ones (regarding AIDS, these would include CD4 count, viral load, and incident opportunistic infections, as well as mortality) or markers of health system utilization (for example, emergency room visits or failure to fill needed prescriptions or to show up for an appointment) or patient satisfaction. Dr. Behforouz’s team has also shown that the cost of providing good community-based care is less than providing hospital-based care with little in the way of follow-up at home—the standard of care that emerged in the United States over the course of the previous century.

For patients with chronic diseases, like AIDS or poorly controlled diabetes or major depression, good hospital care with little community-based care usually adds up to mediocre outcomes.

Shifting efforts towards the home and towards prevention, including secondary prevention of poor outcomes among those already diagnosed with AIDS or diabetes or major mental illness, leads to better outcomes. Quality goes up, as of course does convenience to patients and their families; costs go down, especially if we tally the costs of inaction. Again, this is what value in health care looks like.

Sustaining this work, and making these arguments against a constant undertow of censorious opinion, is hard work—even though the arguments are, as readers of The Upstream Doctors will learn, irrefutable. The formal health care system, including the hospitals and clinics, don’t routinely recruit, train, credential, or pay community health workers; its institutions are not rewarded for doing so any more than they are for helping clear an apartment of mold or mildew. It is against precisely such perverse incentives that the protagonists of systems change in U.S. health care, including physicians like Heidi Behforouz and Rishi Manchanda, and innovative organizations like HealthLeads and HealthBegins, now struggle. And a struggle it is.

Some of these protagonists, including those of HealthBegins, are featured in this book. That’s because Rishi Manchanda and two other physician-rescuers decided to swim upstream against this undertow to found a health start-up, a “think-do tank” that might help address upstream problems in Los Angeles and beyond even as they seek to train a new generation of providers able to make these links between the large-scale and the local and to remake our very notion of what medicine is. HealthBegins’ protagonists include the patients, of course, but also community health workers and health activists and human rights lawyers and others who are building a vibrant movement in Los Angeles. They are, for example, the authors of the important “South LA Declaration of Health and Human Rights” and have worked within high schools and hospitals and other institutions to teach and learn more about health equity and to engage the citizenry to do so, too. Manchanda and others have helped to start and staff a clinic for homeless veterans in LA, who are often, because of a lack of a safety net to catch them before they hit the ground, among the “super-utilizers” of emergency and hospital care. They are also key faculty in an ambitious effort to train or re-train doctors and nurses as upstreamists, and thus to improve care delivery while leveraging the very care process with the opportunity to learn and to innovate, and to improve health for those who too rarely enjoy it.

Our world badly needs more upstreamists, especially those who do not ignore the need to innovate in system design and to incorporate new technologies into an equity agenda.

Clinicians need, early in their training, to understand the ways in which poverty and other structural or extra-personal forces (including institutionalized racism and gender inequality) can constrain the agency of patients. We’ve used the term “structural violence” to describe the harm done to people in this way, and have documented this harm, and discordant claims of causality regarding its origins, in Haiti and other settings of extreme poverty. But that harm is readily enough registered in the United States and, as Manchanda recounts, in a wealthy, inegalitarian and (sometimes) ostentatious metropolis in California. The state is the birthplace, after all, of some of the technologies that might be harnessed to the needs of those served by organizations like HealthBegins or the Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team. Given all of the resources there, can’t we find new gizmos to prevent or mitigate that harm? The Upstream Doctors answers this question with a cautious optimism born of experience in a broken system. Manchanda wants new tools and new “platforms” but knows they will be effectively deployed—they will only prove “scalable”—if they are linked to serious efforts to reform the system.

The lessons learned by Manchanda, which are succinctly summarized in this book, are also an antidote to simplistic “solutionism,” which holds that the U.S. health care crisis (or other complex social problems) can be addressed through technological innovation alone. Evgeny Morozov cites a couple such enthusiasts, who are representative of such strains of solutionism. According to one of them: “Instead of paying doctors and hospitals to repair your body, you can monitor yourself to avoid illness. Instead of heeding marketeers’ offering of fast foods and instant pleasures, you can set up your own life so that you’re bombarded with messages promoting health and conscientiousness.” Morozov’s riposte is caustic but dead-on: “Here is the mid-set of an atomized consumer who couldn’t care less about health care reform but is only preoccupied with maximizing his or her own well-being.”

In contrast to some of our colleagues in social medicine, Rishi Manchanda is no Luddite. His book is rife with enthusiastic stories about new technologies that can help us “quantify the self,” and about the need for electronic medical records and new online platforms that can help upstreamists and their neighbors and allies come together to solve many of the daunting problems laid out in The Upstream Doctors. This is the work of social entrepreneurs. Nor does Manchanda believe that we all need to focus on prevention rather than care, or to reject sound, if downstream, clinical strategies and tools as distractions. Too often, the Stanford pediatrician Paul Wise warned us 20 years ago, “those who elevate the role of social determinants indict clinical technologies as failed strategies. But devaluing clinical intervention diverts attention from the essential goal that it be provided equitably to all those in need. Belittling the role of clinical care tends to unburden policy of the requirement to provide access to such care. In a time of growing conviction, in certain circles, that smart technologies will solve all of our social problems, it’s important to acknowledge that technology, including diagnostic and therapeutic innovations, can help us solve many health problems, but only if we remember the importance of using it fairly and wisely and compassionately. The real problem with many new technology schemes, as Morozov notes, is not that they’re “too smart” but rather that they’re not smart enough: “a truly smart system would find a way to turn us into more reflective, caring, and humane creatures. Technology can certainly assist in that mission, but both the technologists and the social engineers guiding them would have to have a very different mind-set.”

Rishi Manchanda and his colleagues at HealthBegins have the right mindset: a deep respect for the tools, new and less so, we need to take care of the sick and to prevent unnecessary suffering; a knowledge of our health care system and its weaknesses and assets; an awareness of the importance of civic engagement in addressing upstream and downstream problems; a good sense of the human resources we might need, upstreamist clinicians among them, to transform American health care delivery. HealthBegins counts a number of practitioners of clinical medicine who do not scant the lessons of social medicine. They want, as do those working with HealthLeads and with Partners In Health, to build “delivery platforms” able to use these tools, and those sure to follow, in an equitable and humane manner.

So in response to my rhetorical question about Dr. Manchanda’s credentials and experience, note that he has, despite his relative youth, already emerged as one of the leaders in the field of social medicine, a field to which he has contributed for well over 15 years. His book will teach or remind you of the importance of this approach—an upstream approach that does not ignore downstream problems—in addressing the structural problems faced by the working poor, like Veronica, or the homeless veterans who are “super-utilizers” of a system not designed to link community-based care to hospitals or even to community health centers. Manchanda’s social activism and civic engagement—the hard work of being a doctor who is also a citizen—can help us to re-imagine a delivery platform that might deliver true value for all those who need.

3. Why should all of us, regardless of where we live and how healthily, care so much about social medicine?

Why should people outside of the medical profession, however broadly conceived, read this book and consider deeper civic participation in the quest for improving our health and our health care? I will offer three reasons to act in support of the proposals laid out neatly in Part V of Manchanda’s volume.

First, understanding and addressing upstream causes of ill health is one of the best ways, as the data almost always show, to improve our collective well-being. But neither the understanding nor the addressing will ensue without the engagement of a broader public beyond health care providers and the administrators of our fragmented health care system. Using a common enough trope, Manchanda terms this “health care transformation powered by you.” Among the reasons that Manchanda returns so frequently to the importance of citizens’ engagement in the pressing topics of our times: there are not enough primary care providers in our country and far too few upstreamists to complement them. All of them who seek to acknowledge and address their patients’ social determinants of health and illness face, in our current system, “regulatory, cultural, and financial obstacles,” including, invariably, the “fee-for-service straitjacket” that has slowed much innovation in care delivery. Manchanda and others know we need a cultural shift that comes only with broader participation and changes in systems and in the rules that govern them. Mindful of Morozov’s critique of the idea that we must bring every citizen-consumer up to speed on arcane and complex topics (“Why do we expect citizens to care about every single issue under the sun, as if the very idea of delegation would ruin our democracy?”) in order to solve them, I would argue that all of us need to learn a lot more about how and when our medical system works—as it did last month in the Boston Marathon bombings—and how and when it doesn’t, as laid out in The Upstream Doctors. Dr. Manchanda and other upstreamists, fond as they are of certain new tools, are not seeking to promote some sort of “omniscient cosmopolitanism” through technological fixes such as those seen in “the quantified self movement.” They argue, rather, that health care—your own, others’—should not be only in the hands of specialists and experts like him.

Second, the current system is, it is widely noted, unsustainable. I will repeat myself here: it is very expensive to give mediocre medical care to poor people in a rich country. Although it may sound crass to say so, the overall health system doesn’t give good value for money. It’s neither efficient nor effective in addressing or preventing many of the chronic problems most of us will one day face. And we all know health care costs an awful lot, although how much it costs isn’t really clear and we can’t rely on hospital bills to tell us much about the true cost of care. It certainly can’t be termed a cost-effective system by any of the standard, often fetishized, criteria so often tossed about in policy and academic debates.

Health care systems can be imbued with the values that may refocus medicine on caregiving.

Third and finally, it’s urgent that we go beyond utilitarian arguments to continue to stake moral claims for improving access to quality health care for all. Increased efficiency and lower costs, though important, are not the alpha and the omega of health care improvement, and still less of improvement in health itself. There is a great need, these days as ever, for compassion for and—dare we say it?—solidarity with those who shoulder the heaviest burdens of illness and premature or unnecessary suffering. Most of these people are not likely to read a TEDBook, nor can they easily heed even loud and incessant reminders to improve, by themselves and with “will power” and perhaps a few new gadgets, their diets, their exercise patterns, and their living conditions. Many of them still live in poverty or hover above it in frightening proximity, only a chronic disease or two away. It’s clear that these patients, on the edge or over it, are Rishi Manchanda’s primary concern, as they are mine. But there’s no reason to believe that we cannot all be part of a broader movement to reject market fundamentalism and its attendant belief that health and health care are just two more in a long line of products that we, the customer or “client,” can consume to good effect. Health is created with others, just as we can together dismantle systems that usually deliver mediocre or downstream or tardy care to the poor and otherwise vulnerable. This is true in rich countries as in poor ones.

We doctors can also work with others—from professions ranging from law to education, from businesses ranging from tech start-ups to food producers, from sectors public and private—to re-imagine and rebuild a health care system that is safe and effective and efficient and able to serve especially those who would benefit from it most. For health care systems, if built by informed and compassionate people like Rishi Manchanda, can be imbued with the values that may refocus medicine on caregiving. For all those concerned with the health and well-being of the poor or otherwise marginalized, of the frail or the elderly, of those bent under the weight of serious illness, The Upstream Doctors offers important ideas and examples of solutions to their current predicament—and thus to our own.

The Upstream Doctors is available now. Get it on Kindle.

Physician and anthropologist Paul Farmer is co-founder of Partners In Health, a nonprofit that provides health care in poor communities in Haiti and across the world. He is the Kolokotrones University Professor and chair of the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and chief of the Division of Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. His most recent book is To Repair the World: Paul Farmer Speaks to the Next Generation.

Physician and anthropologist Paul Farmer is co-founder of Partners In Health, a nonprofit that provides health care in poor communities in Haiti and across the world. He is the Kolokotrones University Professor and chair of the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and chief of the Division of Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. His most recent book is To Repair the World: Paul Farmer Speaks to the Next Generation.

Comments (25)

Pingback: How to change the world « E-Learning

Pingback: Exhibit at Our Conference and Reach Hundreds | California School Health Centers Association

Pingback: Save the Date for Our 2014 Conference | California School Health Centers Association

Pingback: Lots of great info… | St John Ambulance (nz) and Local Timebanks

Pingback: TED News in Brief: Chrystia Freeland runs for office, Matt Damon tells a TED-related story | Best Science News

Pingback: TED News in Brief: Chrystia Freeland runs for office, Matt Damon tells a TED-related story | Krantenkoppen Tech

Pingback: Paul Farmer: Investigating the root causes of the global health crisis | TED Blog « GOOD MEDICINE IN BAD PLACES

Pingback: Tackling sickness at its source: An interview with TED Book author Rishi Manchanda | National Physicians Alliance

Pingback: “The Upstream Doctors” – An Accompanying Essay | BWH Global Health Hub

Pingback: Tackling sickness at its source: An interview with TED Book author Rishi Manchanda | BizBox B2B Social Site

Pingback: Tackling sickness at its source: An interview with TED Book author Rishi Manchanda | Krantenkoppen Tech

Pingback: MAQUILLAGE DU JOUR!