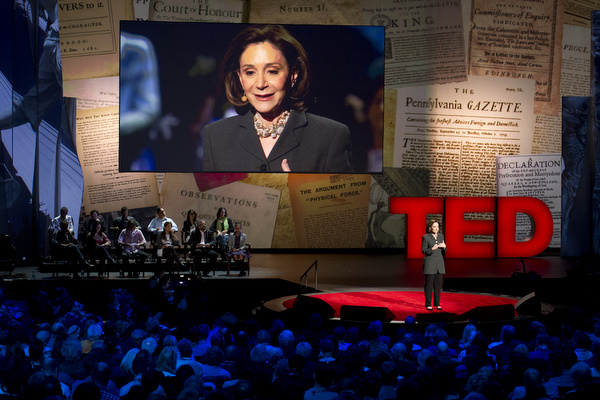

Photo: James Duncan Davidson

Just a moment ago Sherry Turkle‘s daughter texted her: “Mom, you will rock.” Turkle loved it, she says. “Getting that text was like getting a hug.” Turkle, who has written extensively on the nature of human relations on the internet, who evangelized the internet, who loves receiving that text, is here to tell us that there may be a problem.

In 1996 she gave her first TEDTalk, “Celebrating our life on the internet.” She was excited, as a psychologist, to take what people were learning in the virtual world and apply it to the physical world. It made the cover of WIRED.

Her new book, Alone Together, will not make the cover of WIRED, she is pretty sure. She is still excited about technology, but is deeply worried that we are letting it “take us places we don’t want to go.” She’s interviewed hundreds of people about their online habits, and she’s come to this conclusion: “The little devices in our pockets are so psychologically powerful that they don’t even change what we do, they change who we are.” Things we do with them were odd, but now seem familiar. We text in board meetings, classrooms and even funerals.

People talk to her about “the important new skill of making eye contact while you’re texting… It’s hard but it can be done.”

Why does this matter? It matters to her because she thinks we’re setting ourselves up for trouble. Constant digital interaction impedes our capacity for self-reflection. “People want to be with each other, but also elsewhere. People want to control exactly the amount of attention they give others, not too much, not too little.” She calls it the Goldilocks effect. But the distances that feel right for some people in some situations, say a boardroom, can be totally wrong in others, such as raising a child.

A teenager says to her, “Someday, someday, but certainly not now, I’d like to learn how to have a conversation.” There is a feeling that conversations are difficult because we don’t have the ability to edit as we talk, and so can’t present the exact face that we’d like to. “Human relationships are rich, and they’re messy and they’re demanding. And we clean them up with technology. We sacrifice conversation for mere connection.”

Stephen Colbert once asked her, “Don’t all those little tweets and texts, all these little sips of information, add up to one big gulp of real conversation?” Her answer is no. All of these little bits work very well for many things, but they don’t work for the real task of learning deeply about each other. Even more, “We use conversations with each other to learn how to have conversation with ourselves.”

Turkle finds that people wish for an advanced version of Siri that will be a friend who will listen when others won’t. The feeling that no one is listening makes us want to spend time with our technology, Facebook pages, robots and others. “Have we so lost confidence that we will be there for each other?” She did research in a nursing home, where she saw a woman who had just lost a child, interacting with an “empathetic” robot seal that seemed to respond to her. The staff was amazed. But Turkle called it “one of the most wrenching, complicated moments in her 15 years of work.”

We’re designing tech that will give us the illusion of friendship without the demands of companionship. They offer us three fantasies:

1) We’ll have attention everywhere.

2) We’ll always be heard.

3) We’ll never have to be alone.

This relationship, this constant connection, “Is changing how people think of themselves, it’s shaping a new way of being … I share, therefore I am.” Turkle believes we need to cultivate a capacity for solitude. “If we’re not able to be alone, we’re going to be more lonely. If we don’t teach our children to be alone, they’re going to be more lonely.”

At TED1996 she said: “Those who make the most of their lives on the screen come to it in a spirit of self-reflection.” She believes the same is true now, and that now is the time to talk about technology. We are still very much the early days of designing technology. There’s time to reconsider how we build and use our digital tools, “to build a more self-aware relationship with them, and with ourselves.”

She has suggestions for how to make room for solitude.

1) Teach it as a value for your children

2) Make spaces, such as the kitchen, to be alone.

3) Listen to each other, including to the boring bits. “When we stumble or hesitate or lose our words, we reveal ourselves to each other.”

She is optimistic that we can do this, but we need to recognize complication, and that we are vulnerable to the allure of false promises of simplicity. “Let’s talk about how we can use digital technology to make this life the life we can love.”

The jury in the room, and the audience, overwhelmingly agree that she is “Not guilty of worrying about the wrong thing.”

Comments (66)

Pingback: FOMO: A Modern Affliction in the Digital Age – MindSip

Pingback: Self-Care: an Attitude, Priority, and Practice – The Irregular Girl Revolution

Pingback: Social media does make us less social. |

Pingback: The Little Devices in our Pockets | sarahgaldenzi

Pingback: Tiempo en solitario | Bianka Hajdu

Pingback: Grupos de LinkedIn, hasta qué punto una oportunidad para destacar | Bianka Hajdu