Dawn Landes performs a song from her new musical, about a woman who rowed the Atlantic Ocean solo. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Pop-Up Magazine is “something like a reading,” only not. This unique show brings the glossy pages of a general interest magazine to life, telling real-life stories in a vortex of sight, sound and spectacle. And they have curated Session 8 of TED2015. A tour of the 11 stories woven on the TED stage:

Believe in Magik*. The lights went up, bringing the stage and audience out of darkness, as Minna Choi + Magik*Magik opened Pop-Up Magazine’s session. The violins and cello began with a steady, elegant hum. Meanwhile, the piano added a low yet hopeful quality. Then one violin struck out in an excited, spiraling solo, leading the way for the accompanying violin to match. The strings then departed and dropped several octaves, creating a somewhat frenzied, ominous sound. In a drastic shift, the piano switched from a supporting role to a lead, engaging the violin in a light, whimsical tip-toe throughout a new melody. Finally, with one musician strumming his violin like a mandolin, the orchestra coalesced into a final surge that was two parts elegant, one part structured chaos. With this, Minna Choi + Magik*Magik set a beautiful tone for the session.

So, how did you meet? Photographer Alec Soth and New York Times photo editor Stacey Baker kick off this session with moving photographs of love and relationships. In their work together, they look at singles and couples — from longtime spouses at a retirement home to single people at the world’s largest speed-dating event. In Las Vegas. On Valentine’s Day. (Stacey was in the hot seat.) In his photographs, Alec hopes to capture an element of vulnerability, as a “physical exterior reveals a crack to the more fragile interior.” Soth and Baker were fascinated by the quality of endurance they saw in all of their subjects. “The world is hard, and the singles were out there trying to connect with other people. And the couples were holding onto each other after all these decades.” One of the last couples Alec photographed for their project at the retirement home both carried the same photo of their wedding day in their wallets. What’s more beautiful: the two people young and happy in this photo, or the two people still holding onto this image decades later?

The birth of a bee. We’ve all heard that bees are in peril. But for his upcoming story in National Geographic, “I wanted to explore what this looks like,” says photographer Anand Varma, as he shows us a thrilling time-lapse of the first 21 days of a bee’s life, as it goes from a clear blob to a furry bee. Crawling around the hive are mites, called varroa destructor, which prey on the developing young bees, making them vulnerable to disease. Most beekeepers fight these mites by treating the hive with chemicals, which also isn’t great for the bees. “Researchers are working on finding alternative methods to control those mites,” says Varma, talking us through an experiment to breed bees for mite resistance, with tough side effects: “The bees started to lose traits like gentleness and the ability to store honey,” essentially, some of the qualities that make them bees. (The photos will appear in the April issue of Nat Geo.)

Anand Varma shares astonishing macro photos of bees — and the challenges they face right now. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

A misunderstood spectrum. Steve Silberman takes us through decades-old history of misinformation and misunderstanding about autism. It started in 1943 with child psychologist Leo Kanner, who was the world’s leading authority on autism at the time. Kanner believed autism was very rare, and indeed his definition was incredibly narrow: He classified it as an “infantile psychosis caused by cold and unaffectionate parents” and wrote off special abilities that he saw in children with autism. “As a result,” says Silberman, “autism became a source of shame and stigma, and two generations shipped off to institutions ‘for their own good.’” English psychiatrist Lorna Wing would later uncover research from 1944 by Hans Asperger that showed a much more progressive view of autism. Asperger saw it “as a diverse continuum that spans an astonishing range of giftedness and disability.” Today the CDC estimates that one in 68 children in the US are on the autism spectrum, and indeed as Silberman shows, there’s no benefit to the stigma. After all, he says, “We can’t afford to waste a single brain.”

A man named Wall Street. For our next story, The Kitchen Sisters — radio producers Davia Nelson and Nikki Silva — take us to San Quentin to meet “Wall Street,” an inmate who buys and trades stocks from the inside. His real name is Curtis Carol — he grew up in Oakland with a mom, and grandmother, addicted to crack. He committed his first crime at age 12. He’s 37 now; he has been in prison for 20 years, The Kitchen Sisters tell us. One day in prison, he picked up the financial section of a newspaper. “A guy asked if I played the stock market. I was like, ‘What’s that?’” remembers Wall Street, his voice heard clearly in the teleplay. “It’s where white people keep their money,” the guy responded. Wall Street was intrigued and found that he was a natural. He has set up an office in San Quentin, and uses the vast spare time that prison affords him to read an estimated 500 articles a week to inform his trades. Wall Street not only advises correctional officers, he helps his fellow inmates make investments, as you don’t exactly build up a retirement plan in jail, working for 15 cents an hour. That’s why, when he gets out, say The Kitchen Sisters, he plans to teach a stock program. “The goal is to give back to the community,” he says. “I learned that Bill Gates and Warren Buffet give 90 percent of their wealth away, and I thought what better way to help the things that I’ve destroyed.”

The human world of bots. One afternoon in 2013, a high school student named Olive noticed something strange in her Twitter account: 30 scantily-clad women had followed her at once. Soon it was hundreds, then thousands. She became something of a hero in school. Journalist Alexis Madrigal explains what happened: these weren’t actual people, they were bots, or “little pieces of code running on the internet using made-up names, stolen pictures and computer-generated bios.” Something in their algorithm was causing these bots to follow Olive. Madrigal introduces us to a few other bots: @pentametron (which looks for tweets in iambic pentameter); @lowpolybot (which creates custom art from photos sent to it); and the powerful @every3minutes (which sends a tweet every 3 minutes to remind us, before the US Civil War, a slave was sold in the US every 3 minutes, by one estimate). “On the one hand these bots are not sophisticated at all. They’re not even Siri,” says Madrigal, “but what they show is that computers don’t need to be as smart as us to do some human-ish things and have very real effects on our lives.” Now, for fun, try tweeting at Madrigal’s @truthdarebot designed for TED2015, and ask it for a “truth” or a “dare.”

Alexis Madrigal shares his favorite twitterbots — and a few not-so-favorites. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

The ocean would hold me. Singer-songwriter Dawn Landes took the audience back to June 1998, when Tori Murden left her job as a project manager in Louisville, Kentucky, and embarked on what no woman had ever done: row across the Atlantic. She set out with her homemade vessel, The American Pearl, a small boat that had no motor or sail. To track her journey, she made videos along the way, even when she lost all radio connection with the outside world. She covered over 1,000 miles and rowed over 200,00 strokes. But she unknowingly rowed into he heart of Hurricane Danielle. After being pummeled by 7-story waves, she was rescued and returned home, miles short of her goal. Tori’s journey inspired Dawn to write a musical called Row. On the TED stage, she shared a song from that musical called “Dear Heart.” With an acoustic guitar in hand, Dawn sang the audience through the quiet frustration Tori felt as she tried but failed to adjust back to normal life, “When I was out there, the ocean would hold me, rock me and throw me light as a child. Now I’m so heavy, nothing consoles me.” In this moving performance, Dawn Landes brings the audience full circle, celebrating Tori’s eventual return to the Atlantic and the realization of her dream.

Letters to North Korea. During the final 6 months of Kim Jong Il’s life, writer Suki Kim lived undercover as a teacher in an all-male evangelical Christian university in Pyongyang. Why? To write about North Korea with any meaning, to “understand the place beyond the regime’s propoganda,” the only option was total immersion. And so she lived with 270 young men who were expected to be the future leaders of the “most isolated and brutal dictatorship in existence. North Korea is a gulag posing as a nation.” As she says: “Everything there is about the great leader. Every book, newspaper article, song, TV program, there is one subject. Flowers named after him, mountains carved with his slogans.” Many of her students were computer science majors, but did not know about the Internet, let alone Facebook or Twitter. “I went there looking for truth. But where do you start when a nation’s ideology, a student’s day-to-day reality, and even my own position at the university were all built on lies?”

Virtual reality as a tool for empathy. Chris Milk was obsessed with Evel Knievel as a kid. “I felt so connected to this world,” he says, “I didn’t want to be a storyteller, I wanted to be a stuntman.” Of course, he didn’t. He became a filmmaker. “It’s an incredible medium,” he says. “But it’s a group of rectangles that are played in a sequence. Is there a way that I could use modern and developing technologies to tell stories in different ways?” This thought has now led him to virtual reality. He shares with us a collaboration between the UN and his virtual reality-focused production company, VRSE.works, called Clouds Over Sidra. This immersive experience brings you to a Syrian refugee camp in Jordan, Za’atari, where you meet 12-year-old Sidra. The film is shot in 360 degrees. “When you’re sitting there in the room, you are not watching through a screen or window, you’re with her. When you look down, you’re sitting on the ground she’s sitting on,” he says. “You feel her humanity in a deeper way.” Milk sees great potential for virtual reality. “It’s a machine, but through this machine we become more compassionate, more empathetic, more connected,” he says. “Ultimately, we become more human.”

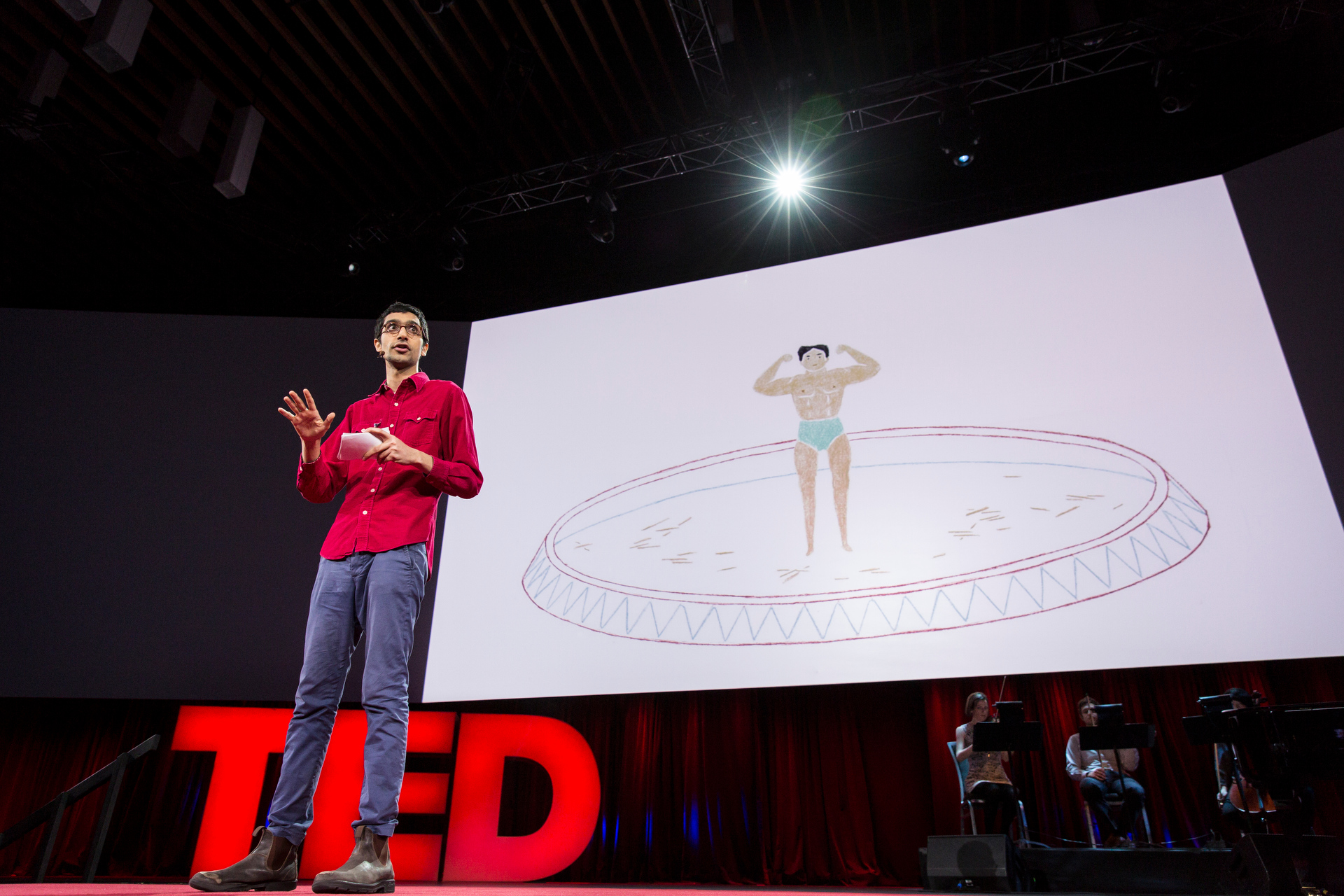

Latif Nasser retells the life story of a circus strongman who invented the field of pain medicine. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

A painful history. After Latif Nasser’s mother was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, he set out to find out more about pain. In his research, he came upon John Bonica, a medical student who moonlighted as a professional wrestler and a circus strongman to pay his tuition. He kept his lives separate, says Nasser, and no one at the circus knew he was a doctor. After all he was “supposed to be a brute and a villain, not a nerdy do-gooder.” The pains and aches of Bonica’s secret life informed his medical career: He became an anesthesiologist, developed the epidural, and even wrote The Management of Pain, known as the “bible of pain,” after realizing that in the medical literature of the time, pain itself was rarely mentioned. Says Nasser, “[Bonica] recast the very purpose of medicine. The goal wasn’t to make patients better; it was to make patients feel better.”

Art and grief. Next up is journalist and poet Dana Goodyear, who tells a heartbreaking story of love, art and mourning. The tale starts with Margaret Kilgallen, an artist with auburn hair and vivid blue eyes who liked to paint and play the banjo. She lived in the Mission in San Francisco with her husband, Barry McGee, and the two of them painted side by side, exploring new art forms like graffiti and old-timey sign painting. As Margaret and Barry’s art-world success grew, they developed a pen-pal relationship with Clare Rojas, a fellow artist and musician. But when Margaret, unexpectedly, died soon after giving birth to a daughter, Clare’s life became more entwined with the husband and child Margaret left behind. Clare eventually married Barry, and adopted their daughter, Asha. Was she simply filling the void Margaret’s death had created in their lives, “living a life that didn’t belong to her, painting a lie, somehow to blame?”

Tape head. Documentary filmmaker Sam Green closes out the session by diving deep into Louis Armstrong’s personal audio-tape archives. The beloved jazz trumpeter was a huge tape recorder enthusiast — he recorded thousands of hours of his life, 750 tapes in all, at a time when hardly anyone used tape recorders. At times the tapes are bawdy, full of talk about sex and drugs and dirty jokes.( In a sense, Armstrong was the prototype for today’s guy who is constantly Instagramming and tweeting.) In one tape, Armstrong tapes a dinner with his wife, Lucille, and Slim Thompson. After Thompson leaves at 5 a.m., Armstrong and Lucille have a flirty argument, Lucille goes to sleep and Armstrong pours himself a drink. For the next five minutes, the tape records silence, of Louis just sitting there. For Green, accustomed to a constant inundation of images and videos, this silence made him feel more connected to Armstrong than ever before.

Sam Green listened to the private audiotapes of Louis Armstrong — bawdy, funny and personal. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

You can watch this session, uncut and as it happened, via TED Live’s on-demand conference archive. A fee is charged to help defray our storage and streaming cost. Sessions start at $25. Learn more.

Comments