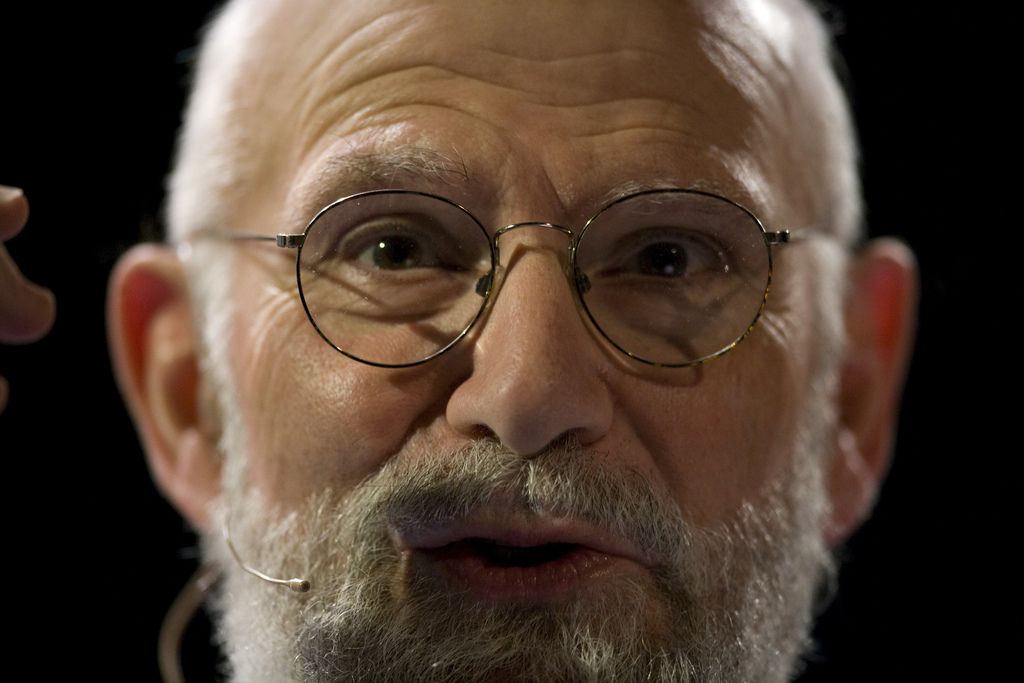

Oliver Sacks speaking at TED2009. Watch his TED Talk, What hallucination reveals about our minds. Photo: Asa Mathat

Neurologist and author Oliver Sacks died on Sunday, August 30, at age 82. He’d announced in February that he was in the final stages of terminal cancer, and wrote a beautiful essay in the New York Times about what that meant to him:

Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts.

Sacks gave a talk in 2009 at TED about visual hallucinations that blind people see — including, it turns out, himself. He was a ceaseless self-experimenter, as our writer Shanna Carpenter found when she visited Sacks in his study, filled with mineral samples and photos and letters, where they talked for an hour about hallucinations, mental illness, and lemur colonies. Their talk was rich and fascinating; it’s worth reading in full. At one point, Shanna asks him:

It is very interesting, your attitude towards the things that are happening in your own body, because it’s one thing to make a case study of others’ lives, but you’ve also made one of your own, rather than getting scared.

No, I do get scared.

But this is how you deal with it?

It serves maybe to put a certain intellectual distance there. But still, I was absolutely terrified with this melanoma at first. I didn’t even know one could have ocular melanomas, let alone that they were much more benign than other sorts. When it was diagnosed, the surgeon brought out a model of an eye and he put in it something that looked like a little, shriveled, black cauliflower. And my immediate thought was that, in England, when a judge is going to pass a death sentence, he puts on a black cap and I saw this thing as the equivalent. I thought, “It’s my death sentence.”

But still, as a neurologist I can’t help that even in my own life, I am always on the lookout for information, for material. We all are. … I’m now surrounded by papers on MRIs and visual hallucinations. I’ve also had my own brain MRI’d.

Did you?

Twice. Once in regard to visual phenomena and once in regard to musical imagery and memory. You know, I have direct access to this brain. I don’t have direct access to anyone else’s mind.

Beloved figure: Oliver Sacks rehearsing onstage at TED in 2009, in a behind-the-scenes snapshot taken by a crew member. Photo: Angela Cheng

Comments (4)