It seems these days, everybody’s getting hacked.

With so much of our most sensitive information stored on servers in some remote part of the world, it seems concerningly easy for malicious hackers to worm their way past secure firewalls and into bank accounts, credit card databases, corporate emails and even hospital systems.

On a global average, these hacks cost companies about $3.6 million, according to IBM’s annual Cost of Data Breach Study with 2016 being a record-breaking year for data breaches in the United States alone — which is shocking, seeing as many breaches still go unreported.

This isn’t exactly news: if you are a digital citizen, then you’re probably aware that nothing is safe on the internet. But beyond hacking, it turns out you’re revealing more than you think with your most casual online behavior.

So, let’s find out: what are you sharing about yourself online?

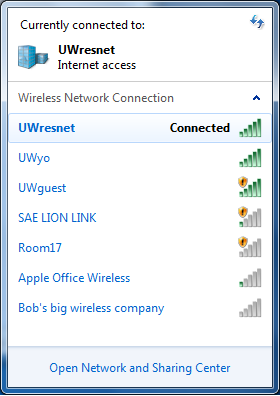

Your Wi-fi may reveal your secrets

A basic but surprisingly telling way to learn about the more undisclosed aspects of your life is through the wireless networks that we connect to daily. Get ready to shift your cell phone to airplane mode …

Whenever you connect to new Wi-fi, your smartphone also beams out a list of the networks you’ve previously connected to, even if you’re not actively using wireless internet, warns cybersecurity expert James Lyne. For hackers, this list is relatively easy to access and exploit. Many companies name their internet after themselves — which means your previous Wi-fi connections can disclose the last hotel you stayed in, the gym you go to and the coffee shops you frequent. This doesn’t include the threats possible when you connect to unsecured hotspots, like when you’re jonesing for free internet while waiting at the airport.

Example from University of Wisconsin

Depending on how uniquely you name your home network, a person might also figure out where you live. For example, say you name your Wi-fi JonesOnElmSt. If a hacker knows some simple information about your household — perhaps the family dog’s name — then she may be able to guess that password too.

So, here’s something for you to think about: “As we adopt these new applications and mobile devices, as we play with these shiny new toys, how much are we trading off convenience for privacy and security?” says Lyne. “Next time you install something, look at the settings and ask yourself, ‘Is this information that I want to share? Would someone be able to abuse it?”

Social media is an obvious culprit

Frank Abagnale Jr. (whose crime spree inspired the movie “Catch Me If You Can”) summed it up neatly in a recent interview with The Wall Street Journal.

“Technology breeds crime—it always has and it always will. There’s always going to be people willing to use technology in a negative, self-serving way. So today it’s much easier, whether it’s forging checks or getting information,” he says. “People go on Facebook and tell you what car they drive, their mother’s name, their wife’s maiden name, children’s name, where they’re going on vacation, where they’ve been on vacation. There’s nothing you can’t research in a matter of a couple of minutes and find out about someone.”

By sharing small aspects of yourself — like the names of your nieces, the high school you attended or the street you grew up on — there’s a possibility that you’re offering up answers to your security questions. It’s hard to avoid sharing these things, but it might be in your best interest to scrub your Facebook and similar accounts and make sure your family and personal information is private or erased.

But say that advice doesn’t resonate, that you’ve been ultra social media savvy and have your accounts under lock and key; you can still give information about yourself quite regularly — not without care, but without thought.

In a fascinating conversation between computer scientist Jennifer Golbeck (TED Talk: Your social media “likes” expose more than you think) and privacy economist Alessandro Acquisti (TED Talk: What will a future without secrets look like?), the two experts spoke at length about the little-discussed aspects of online privacy.

Here’s a boiled down version of their most interesting points:

- The most casual and random behavior reveals a lot. “You can ‘like’ Facebook pages, you can post these things about yourself, and then we can infer a completely unrelated trait about you based on a combination of likes or the type of words that you’re using, or even what your friends are doing, even if you’re not posting anything. It’s things that are inherent in what you’re sharing that reveal these other traits, which may be things you want to keep private and that you had no idea you were sharing.”

- Having social media (and apps) means you forfeit your personal data. “There are terms of service that regulate the sites you use, like on Facebook and Twitter and Pinterest — though those can change — but even within those, you’re essentially handing control of your data over to the companies. And they can kind of do what they want with it, within reason. You don’t have the legal right to request that data be deleted, to change it, to refuse to allow companies to use it. Some companies may give you that right, but you don’t have a natural, legal right to control your personal data. So if a company decides they want to sell it or market it or release it or change your privacy settings, they can do that,” says Golbeck.

- Policymaking for privacy in the US needs work. “The policymaking effort in the U.S. focuses almost exclusively on control and transparency, i.e. telling users how their data is used and giving them some degree of control. And those are important things! However, they are not sufficient means of privacy protection, in that there are a number of ways in which transparency control can be bypassed or muted. What we are missing from the Fair Information Practices are other principles, such as purpose specification (the reason data is being gathered should be specified before or at the time of collection), use limitation (subsequent uses of data should be limited to specific purposes) and security safeguards.”“To be clear, I’m not suggesting that all this information will be used negatively, or that online disclosures are inherently negative. That’s not at all the point,” says Acquisti. “The point is, we really don’t know how this information will be used.”

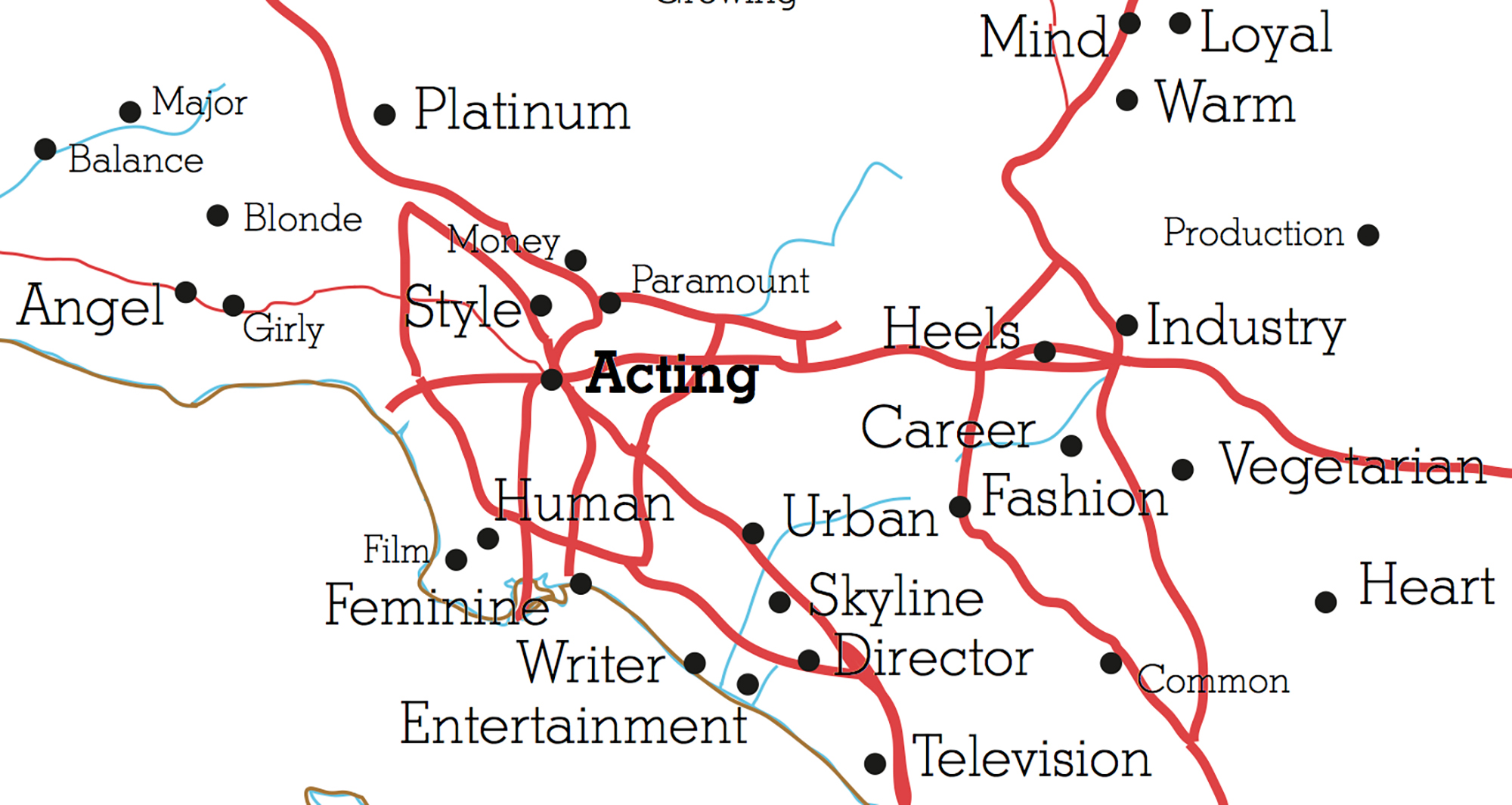

Case in point is Luke R. DuBois’ project “A More Perfect Union.” Dubois created profiles on 21 different dating services and used the data given by other users to piece together a compelling cartographical tapestry of adjectives that describe towns across the US.

Los Angeles’ word is “acting.” And all towns around the area, are similar Hollywood words like “director,” “film,” “blonde” and “career.”

For a sampling of what he learned, check out the TED Ideas blog article or watch the talk to learn more about the data visualization, plus other projects he’s worked on:

Don’t fret — just be vigilant and proactive

A majority of us are at the fault of weak code and the exploitation of human nature.

Privacy researcher and TED Fellow Christopher Soghoian (TED Talk: How to avoid surveillance … with the phone in your pocket) details five easy ways to keep your data safe:

- Outsource your passwords to a robot. The human brain can only remember so many passwords, and too often we just reuse passwords across Facebook, our favorite shopping sites … and our bank. This is a Very Bad Idea. Once hackers break into one website and steal a database of email addresses and passwords, they’ll try to use those same email+password combinations to log in to other sites. The solution: Use a password manager, a software tool for computers and mobile devices, which will pick random, long passwords for each site you visit, and synchronize them across your many devices. Some popular password managers are 1Password, Dashlane and LastPass.

- Get a U2F key — and/or use two-factor authentication wherever possible. Make sure that even if someone learns your password, they won’t be able to log in. To do this, you’ll want to enable two-factor authentication, a security feature that can be added to many online accounts. For some sites, this step can take the form of a random number sent to your phone by text message, or a special app on your smartphone that generates one-time login codes. Google has pledged to upgrade their two-factor authentication in light of the many recent high-profile attacks. If you’re traveling, get a U2F security key, a thumb-drive-sized device that fits into the USB port. When you login to an account from a new computer, the U2F key handles your two-factor authentication. It costs about $15.

- Enable disk encryption. If you lose your laptop or your phone and it doesn’t have disk encryption turned on, whoever finds the device can get all your data too. On the iPhone and iPad, disk encryption is turned on by default, but for Windows, Android or Mac OS you need to make the effort to switch it on. Here’s how to encrypt your disk drive like you mean it.

- Put a sticker over your webcam. There are software tools used by criminals, stalkers and generally creepy people that allow them to turn on your webcam without your knowledge. Granted, this doesn’t happen millions of times a year, but the horror stories are real and terrifying. One simple sticker means you use your webcam when you choose to use it. (You may also want to cover your microphone.)

- Encrypt your telephone calls and text messages. The voice and text message services provided by phone companies are not secure and can be spied on with relatively inexpensive equipment. Your own government, a foreign government, criminals, hackers and stalkers could listen to your phone calls and read your text messages. Some Internet-based mobile apps that you likely already use are much more secure, enabling you to talk privately to your loved ones and colleagues, and don’t require that you do anything or turn on any special features to get the added security protections — Apple’s FaceTime and WhatsApp on Android are both good. If you want an even stronger level of security, there is a fantastic free tool called Signal available on Apple’s App Store.

In 2016, Kevin Roose, a tech columnist for the New York Times, hired hackers to tear apart his online life to learn firsthand how to avoid such a harrowing, paralyzing experience. In his article, How to Not Get Hacked, According to Expert Hackers, Roose outlines some key strategies to keep yourself from being raked over hot coals by some strangers online — a lot of which lines up with Soghoian’s advice. He suggests things like using a VPN (Virtual Private Network) for $3.99/month if you use hotel or coffee shop Wi-fi or familiarizing yourself with urlquery.net to avoid potentially sketchy websites.

… Or if you don’t care about keeping your information secure, you can could do what artist Hasan Elahi did and share everything about yourself all the time and post it to a website in real-time.

Whatever your preference, managing your digital life is difficult and sometimes feels impossible with the amount of steps you have to take in order to achieve some sort of peace of mind. Take these facts and steps in stride, do what you can to protect yourself and in the meantime draw your own selfie — using your personal data. Good night and good luck.