Noah Zandan has analyzed speeches from visionary leaders — from Sheryl Sandberg to Elon Musk — to figure out what they have in common. He spoke onstage at TED2016 on Tuesday, February 16, 2016. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Pay attention. The talks in Session 4 offer takeaways you’ll find yourself using in everyday life — from a new way to end an argument, to how to talk about gravitational waves at a party, to the hidden benefits of learning a foreign language.

Recaps of the talks in Session 4, “Life Hacks,” in chronological order.

What the discovery of gravitational waves means. “1.3 billion years ago in a distant, distant galaxy, two black holes locked into a spiral, falling inexorably toward each other, and collided,” says theoretical physicist Allan Adams. They didn’t spiral slowly — think more like your blender: the densest objects in the universe, spinning at a rate of 100 times per second. “All that energy was pumped into the fabric of time and space itself,” says Adams, “making the universe explode in roiling waves of gravity.” These waves are still in motion today, though they’re now “preposterously weak.” About 25 years ago, a group of scientists decided to build a giant laser detector to search for gravitational waves. It’s called LIGO, and on September 14, 2015, it noticed something. The waves from that collision “passed through the world. They passed through you and me,” says Adams. “Every single one of you stretched and compressed under the weight of that wave.” The detector noticed this anomaly, unthinkably small — less than 1/1000th of the radius of the nucleus of an atom. And yet, says Adams: “Listening to changes in amplitude and frequency of those waves, we can hear the story. We can literally hear the universe speaking to us.” He says that this will be the lasting legacy of the discovery: we can now hear the universe, rather than having to see it. Every “rustle and chirp” will give scientists new clues into the history of the universe.

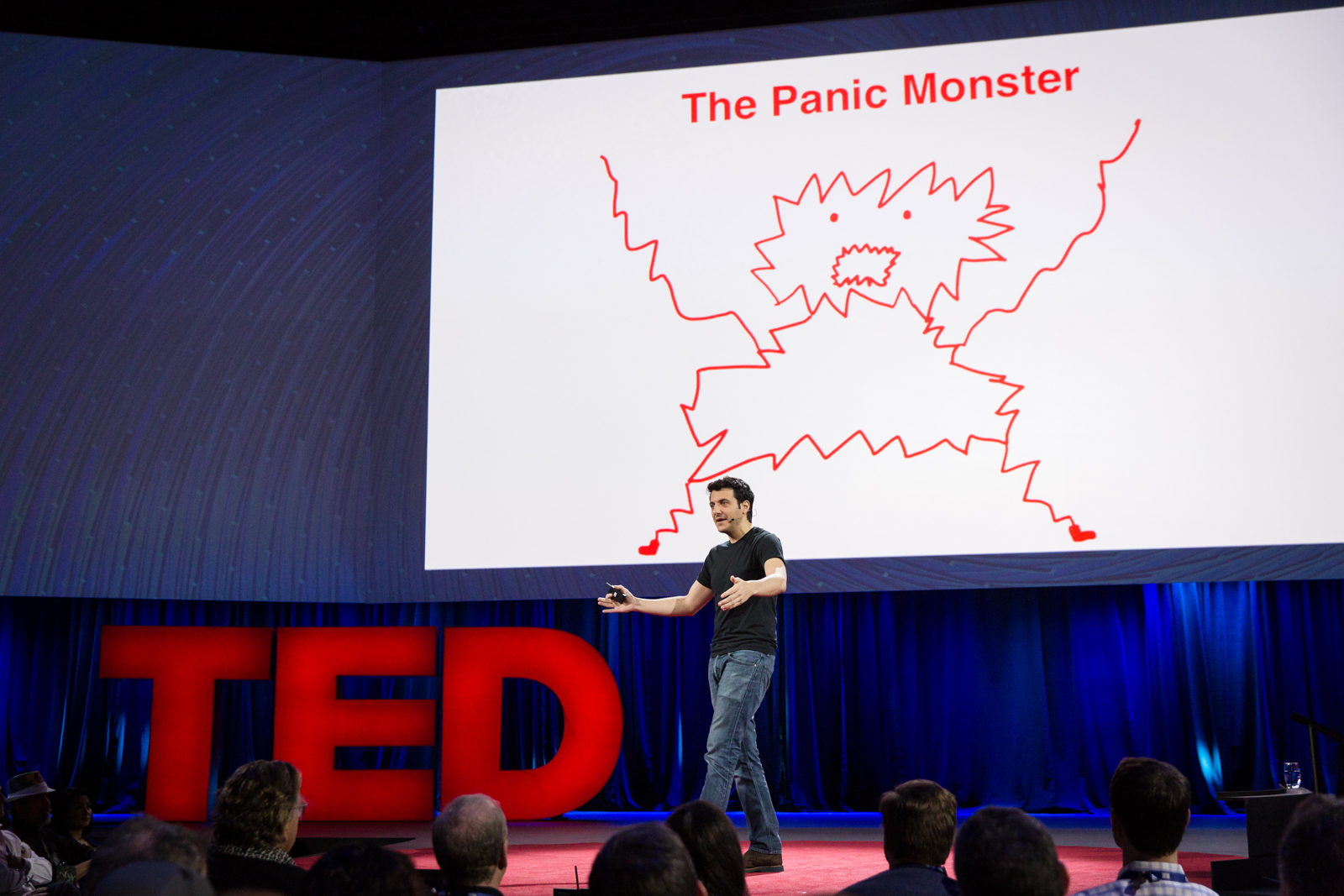

The mind of a procrastinator isn’t pretty. There’s absolutely no good reason to wait until three days before your 90-page senior thesis is due to start writing it. Tim Urban of Wait but Why knows it. And yet … it happened. He knows that procrastination doesn’t make sense, but he’s never been able to quite shake his habits. In fact, he believes that procrastinators have different minds from normal people. Normal people have an agent in their mind that’s a rational decision-maker — and procrastinators have those, too, but they also have a second agent: the “instant gratification monkey,” who lures them away from productive activities with promises of YouTube binges and Wikipedia rabbit holes and bouts of staring out the window. Luckily, there’s a third agent in the mind of a procrastinator: the “panic monster.” This monster, says Urban, scares the monkey into disappearing and puts the rational decision-maker back in charge. “It’s not pretty,” he says, “But in the end it works.”

Tim Urban from Wait But Why shows what the inside of a procrastinator’s brain looks like. He spoke onstage at TED2016 on Tuesday, February 16, 2016. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

The positive power of failure. Organizational psychologist Adam Grant studies “originals”: successful people who dream up new ideas and take action to put them into the world. Originals aren’t the type-A overachievers you might think they’d be. Instead, they’re nonconformists who feel doubt and fear, have bad ideas … and procrastinate. In his research, Grant found that “pre-crastinators,” people who get their work done well in advance, are actually less creative than those who put off work and give themselves time to think in nonlinear ways and develop new approaches to a task. He’s also found that originals have the ability to look at something they’ve seen many times before and see it with fresh eyes, an idea Grant calls “vuja dé,” the opposite of déjà vu. The worst fear of originals isn’t failure — it’s not trying. “The greatest originals are the ones who fail the most, because they’re the ones who try the most,” Grant says. “You need a lot of bad ideas in order to get a few good ones.”

How we transcend our personality traits. Personality psychologists like to talk about traits: shared behaviors that combine to make us who we are. But Brian Little is most interested in those moments when we transcend our personality traits — sometimes because our culture demands it of us and sometimes because we demand it of ourselves. He takes as his example the mysterious introvert who acts like an extrovert — read why in our full recap of his talk.

Alzheimer’s after time. David Larson was only three months into medical school when he felt completely burnt out. He was doing exactly what he was told — going to eight hours of lectures and studying for three hours — and if he was lucky, he got even five hours of sleep a night. So he came up with a clever plan to help him study and in the process totally upend the way we’ve been learning for the past 1,000 years: set your lectures notes to the tune of Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time.” OK, maybe that’s not so revolutionary, but we bet you won’t forget: “If you’re lost, you can look and find 4 APOE.”

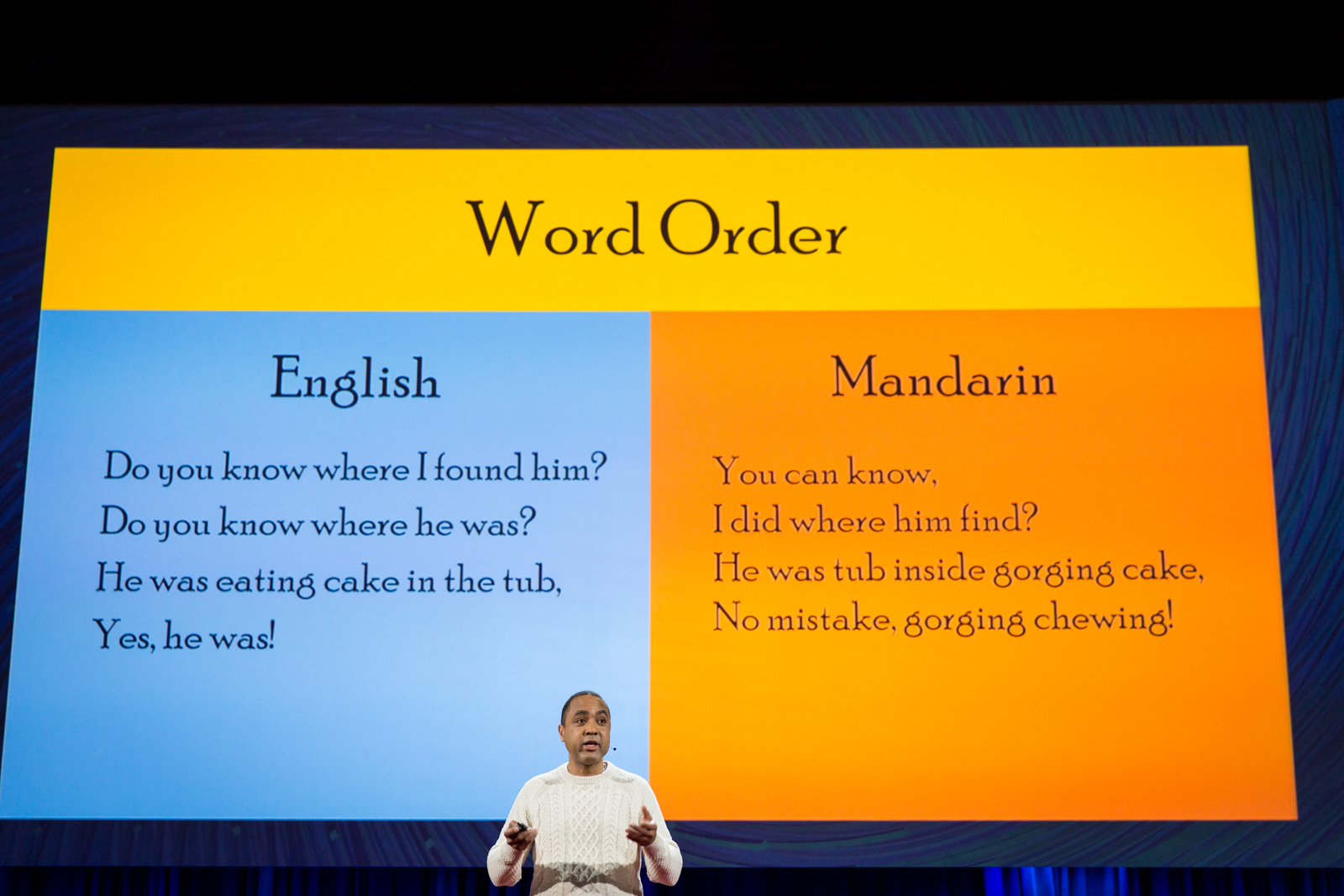

Linguist John McWhorter revels in the act of learning new languages — for their sheer mind-blowing strangeness. He spoke onstage at TED2016 on Tuesday, February 16, 2016. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Why should we learn another language? English is quickly becoming the world’s universal language. It’s already the de facto language of business, diplomacy, the Internet, air traffic control and music, and real-time speech translation is getting better every year. So is it worth it to learn a foreign language? Linguist John McWhorter says it is. Of course, if you really want to enter and “imbibe” a different culture, you have to be able to communicate in that culture’s language. Likewise, it’s been shown that speaking two languages makes you a better multitasker, and less likely to get dementia. But finally, and most compellingly, “Languages are simply really, really cool,” he says. There’s a thrill to mastering things like the different word order or vowel formations of a truly foreign language. “It won’t change your mind,” McWhorter says, “but it most certainly will blow your mind.”

How visionary leaders talk. Noah Zandan is a data scientist who analyzes communication, and he was curious: what makes a CEO or politician sound compelling? He set out to analyze how leaders talk, and he noticed three things about these people he calls visionaries. The most striking thing: “I assumed they would create this vivid picture of future world with all its benefits, but the distinguishing factor was that they speak in the present.” They say “we plan to achieve these results” versus “we will achieve these results” — they talk 15% more about today and 14% less about tomorrow. The second thing Zandan noticed: visionary leaders communicate with clear, simple language. They focus on cause and effect, and speak 20% more clearly than the average communicator. The third thing: they favor the second-person pronoun “you,” and opt for sensory language, the kind of words that pop ideas to life for listeners. “We all want to hear vision and we all want our visions to be heard,” says Zandan. “With data we now know how.”

In defense of strangers. When we talk to strangers, we shift our perceptions on who counts as human. And as Kio Stark, author of the upcoming TED Book When Strangers Meet, says, “Seeing someone as an individual is a political act.” Stark wants you to try talking to more people you don’t know. She personally loves speaking to strangers: she makes eye contact in the street, says hello, listens. One day in New York when an old man told her not to stand on a storm drain because she “might disappear,” she thought it was silly — but she stepped off. And they had a moment. In many parts of the world we’re taught not to trust strangers. “Instead of using our perceptions and making choices,” she says, “We rely on this category of ‘stranger.’” But, says Stark, there are two great benefits to talking to strangers: first, it brings a special form of closeness we can’t get from friends and family, because there are no consequences; and second, we often expect loved ones to read our minds, and with strangers we have to tell the whole story to be understood. It’s a practice all of us should take on.

Kio Stark advocates talking to strangers — and offers three tips for better stranger convos. She spoke onstage at TED2016 on Tuesday, February 16, 2016. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Comments (3)