Arthur Brooks looks for a fresh take on leadership that speaks to both liberals and conservatives. He spoke onstage at TED2016 on February 18, 2016. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

The speakers in Session 9, “Outside the Box,” offer surprising perspectives. From a writer who’s a misfit in a true sense of the word to a District Attorney who asks if prosecuting is really the only way, to a “brain hacker” who truly has the ability to eavesdrop on dreams, prepare to have your mind blow.

Recaps of the talks in Session 9, in chronological order.

Our big differences aren’t that big after all. Social scientist Arthur Brooks remembers the first time he saw real poverty: a child in east Africa, covered in flies, in National Geographic. The vision haunted him, and as he grew up, he wondered: Had things gotten better or worse for the world’s poorest people? The answer changed his life. From 1970 until today, the percentage of the world’s population living at starvation levels has declined by 80 percent. “This is a miracle,” he says. “It’s the greatest anti-poverty achievement in the history of mankind.” Brooks wanted know why this had happened. Surveying economists on the left, right and in the center, he found the answer: “It was the free enterprise system spreading around the world that did that.” But how do we progress again — how do we pull together the world-changing energy to raise the next 2 billion out of poverty — when both conservatives and liberals believe that they alone are motivated by love while their opponents are motivated by hate? It’s not good enough to tolerate people who disagree — we have to realize that we need people who disagree. Brooks challenges all of us be the person who blurs the lines, who’s hard to classify and unpredictable. “If we do that,” Brooks says, “we might just be able to take the ghastly Holy War of ideology that we’re suffering under … and turn it into a competition of ideas.”

The hidden power of prosecutors. We know the American criminal justice system needs reform. It’s the country with the most incarcerations in the world, where predominantly brown and black men get sized up by predominantly white judges and lawyers and sent to jail, changing their lives irreparably. Yet when we think about this reform, says Massachusetts’ Suffolk County assistant district attorney Adam Foss, we leave out a crucial part of the system: prosecutors. At the heart of criminal justice, prosecutors decide whether to send a person to jail, but they’re discouraged from being creative at their jobs or taking risks. Says Foss, “I came out of law school expected to do justice, but I never learned what justice was in my classes. None of us do.”

John Legend plays “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye after a talk from his friend Adam Foss. He took the stage at TED2016 on February 18, 2016. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Redemption songs. With his clear voice and expressive piano playing, John Legend treats us to his stripped-down versions of Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” and Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song.” As a bonus, we get to see a taped performance from James Cavitt, an inmate at San Quentin who has deep thoughts on redemption … including his own. Cavitt is part of the Last Mile program at San Quention.

Confessions of a misfit writer. Lidia Yuknavitch describes herself as a “card-carrying misfit.” She’s the author of the beautiful, raw and critically acclaimed memoir The Chronology of Water, but as she reveals to the TED audience, it took her more than a decade to write it. The words weren’t the problem — the issue was seeing the value in her personal story. Read about the bumps on her journey to published “misfit writer” in a detailed recap of her talk.

Experiments in the science of dreaming. We spend a twelfth of our life dreaming, most of which is forgotten when we wake up. But what if we could start accessing them, recording them or even shaping them? Neurosurgeon Moran Cerf studies the underlying mechanisms of our brains by eavesdropping on their activity using electrodes. By looking at memory-specific cells in the brain, Cerf’s team found that we can know what the waking brain is thinking before it’s able to speak or act. Extrapolating from that, “We had the idea that maybe the same neurons that fire when you’re awake are going to survive when you’re sleeping,” Cerf says; “after all, it’s the same brain.” In one study, Cerf had a brain surgery patient memorize a story and go to sleep, telling the patient he would be asked to repeat the story upon waking up. The results showed that the parts of the brain that corresponded to the features of the story were active while the patient was asleep. “Something about the content is preserved,” he says. Where could this lead us? “To a new canvas that flickers to life when we fall asleep … to a better understanding of ourselves,” Cerf suggests.

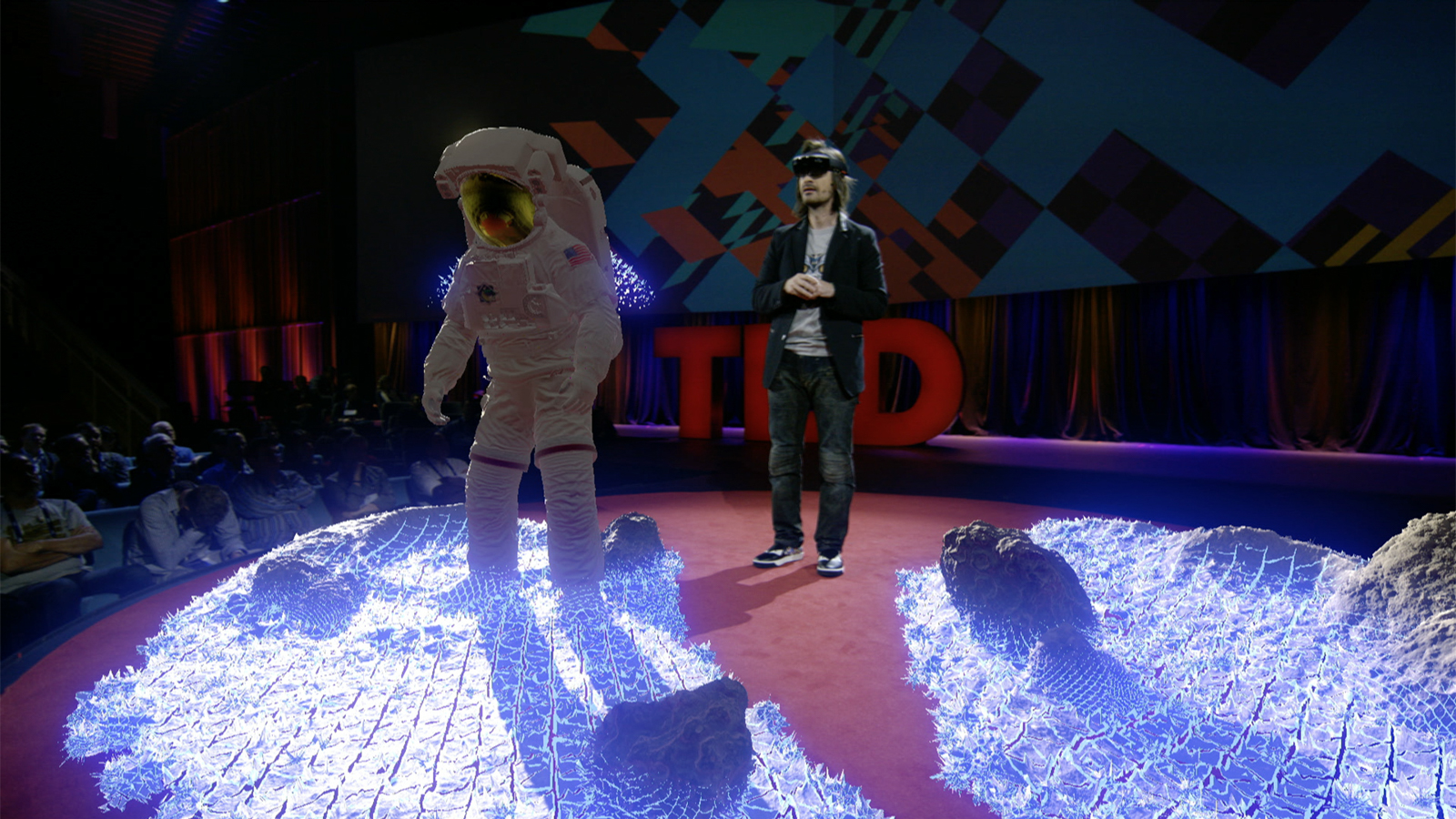

The future is 3D. Again. When it comes to computers, we’re still cave people — we’ve barely discovered charcoal and started drawing in our caves, says Kinect creator Alex Kipman. He believes that thousands of years from now, we’ll look back on our current era as a pretty weird time — “a singular 100-year period in the vastness of time where humans communicated, were entertained and managed their lives from behind a screen.” We’re stuck in 2D, says Kipman, and it’s time to move forward to 3D. (Again.) Donning a Microsoft HoloLens, he shows the world as he hopes we’ll soon see it: a marriage of technology and our physical world. He beams in Jeff Norris from the NASA Jet Propulsion Lab as a holographic telepresence; Jeff is in a room across the street from the theater but also appears to be on the TED stage (and simultaneously on Mars). These kinds of experiences are coming, and they’re going to be ubiquitous. Says Kipman, “Our children’s children will grow up in a world devoid of 2D technology.”

Alex Kipman demonstrates the new Microsoft HoloLens onstage at TED2016 on February 18, 2016. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Comments