Host Chris Anderson interviews Linus Torvalds at TED2016 – Dream, February 15-19, 2016, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

So much of our world is determined by code — be it the code of life or a string of 1s and 0s. In this session, “Code Power,” we hear from Linus Torvalds, who changed how code is written, and from Girls Who Code founder Reshma Saujani, who wants to open up the field dramatically. And after examining the particular code of punctuation at the New Yorker, we get two incredible tech demos.

Recaps of the talks in Session 6, in chronological order.

Inside an open-source mind. Linus Torvalds transformed technology not once, but twice. First, with the Linux kernel, which helps power the Internet; and again, with Git, the powerful source code management system used by software developers worldwide. (If you have an Android phone, you carry Torvalds’ code around with you in your pocket.) Opening Session 6 in conversation with Chris Anderson, Torvalds discusses his work habits, the beginnings of Linux, his love of email, his stubbornness, the merits of open-source code and the idea of taste in code. Despite his massive impact on the world, Torvalds says he isn’t a visionary. “I’m an engineer,” he says. “I’m perfectly happy with all the people who are walking around and just staring at the clouds and looking at the stars and saying, ‘I want to go there.’ But I’m looking at the ground, and I want to fix the pothole that’s right in front of me before I fall in.”

The “bravery deficit” of girls. “We’re raising our girls to be perfect, and we’re raising our boys to be brave,” says Reshma Saujani. Lamenting the “bravery deficit,” the founder of Girls who Code has taken up the charge to socialize our young girls to take risks and learn to program — two skills they need together to move society forward. Read the full recap.

Onstage at TED2020: A TED Talk from an AI (and friends). In the year 2020, three talks at the annual TED Conference will be given by AIs or AI-human partnerships. The one that does it the best, as voted by the audience, will win the bulk of a $5 million X Prize. Read more about the just-announced IBM Watson AI X Prize presented by TED.

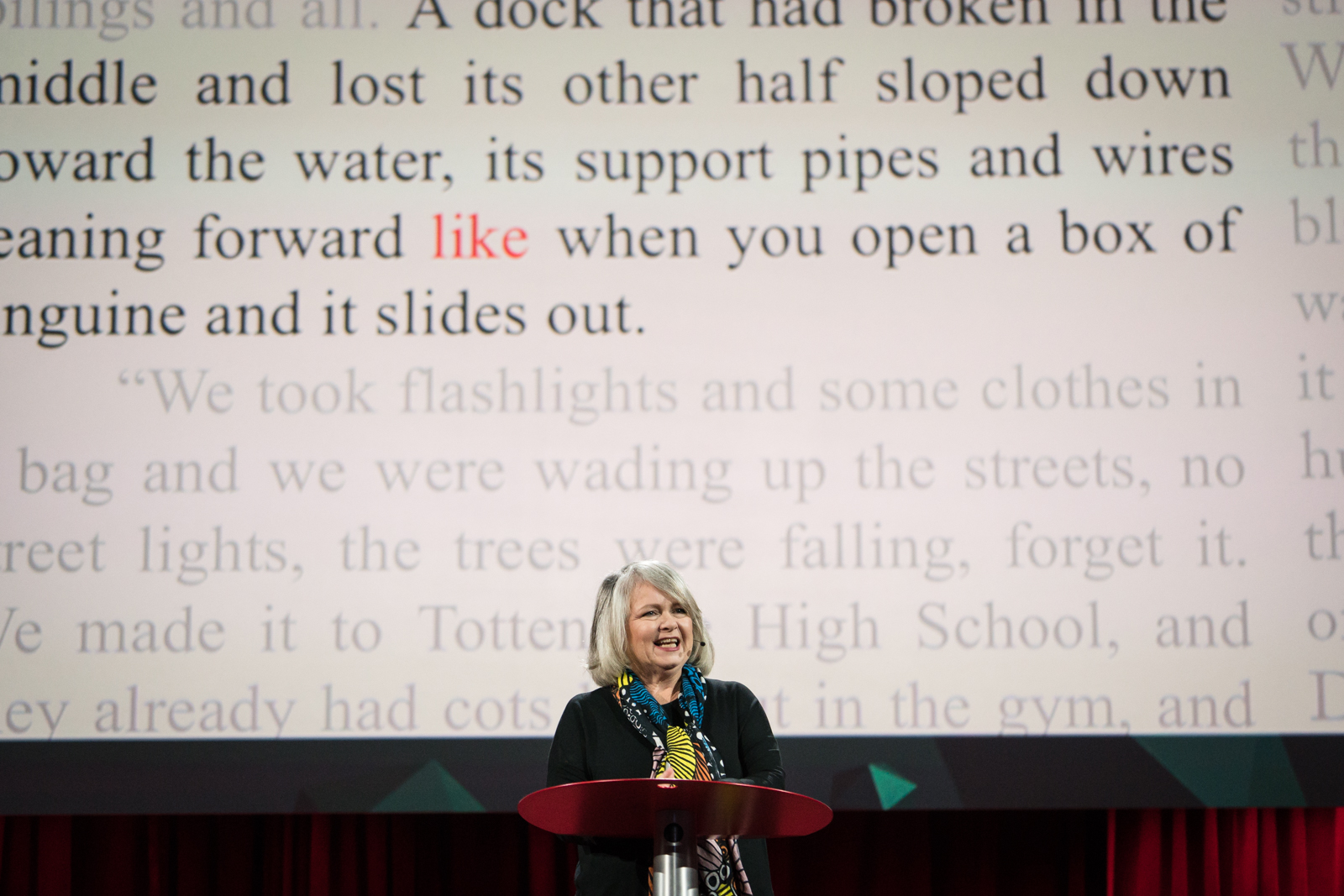

Mary Norris speaks at TED2016 – Dream, February 15-19, 2016, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

The Comma Queen speaks. “Copy-editing for The New Yorker is like playing shortstop for a major league baseball team. Every movement gets picked over by the critics,” says Mary Norris, who has played this position for the past three decades. In that time, she’s gotten a reputation for “sternness” and for being a “comma maniac,” but this is unfounded, she says. Copy-editors work at the level of words and punctuation, and their goal is not just to prevent mistakes but to give each thought emphasis. She upholds the rules of grammar and style, but far above that, she aims to “make the author look good.” She shares a sentence written by Ian Frazier in a story about Hurricane Sandy and walks us through her decision whether to use “as,” which was technically correct, or “like,” which the writer had chosen and which, admittedly, sounded better. “I decided that Hurricane Sandy conferred poetic justice on the author,” she says, “and let the sentence stand.”

Art made of data. Conceptual artist R. Luke Dubois makes unconventional portraits — of presidents, cities, himself and even Britney Spears — using data. Each one of his projects provide a new visualization of the data available to us. For one, Dubois wanted to re-create the US Census in a way that actually told the story of America instead of collecting lifeless data such as age and occupation. To do this, he joined 21 dating websites and captured the profiles of 19 million Americans. Using the data, he redrew a map of America, replacing city names with the word people use more in that city than anywhere else. For another project, he created an art installation using a Walther PPK 9mm handgun that had been used in a shooting in New Orleans. The gun fires a blank every time a 911 call reports a shooting in the city, as the bullet casings pile up around it. “You call this data visualization,” he says. “When you do it right, it’s illuminating. When you do it wrong, it’s anesthetizing. It reduces people to numbers. So watch out.”

Meron Gribetz speaks at TED2016 – Dream, February 15-19, 2016, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

When you are the OS. “Today’s computers are so amazing, we fail to recognize how terrible they are,” says Meron Gribetz of Meta. He’s noticed what many of us have too – that computers and smartphones take us away from our surroundings. He wants “a more natural machine,” one that will “extend our minds and our senses instead of going against them.” With that, he puts on a headset and demos his company’s Meta 2 augmented reality technology for the first time. It’s very cool. With the headset on, you can grab and place holographic objects where you want them. He shows us an architect working on a design for a room, turning and shaping it in space; a professor holds and turns a holographic “glass brain.” The Meta 2 lets you organize things spatially in the real world – if you’re at your desk, you can put holographic email to your left, and the image of a car you’re thinking of buying on your right. When you get a phone call, a hologram version of your friend appears in front of you, as Gribetz demos live onstage with a call to his engineer Ray. Gribetz calls the Meta 2 a “zero-learning curve computer” in which, as he says, “You are the operating system.”

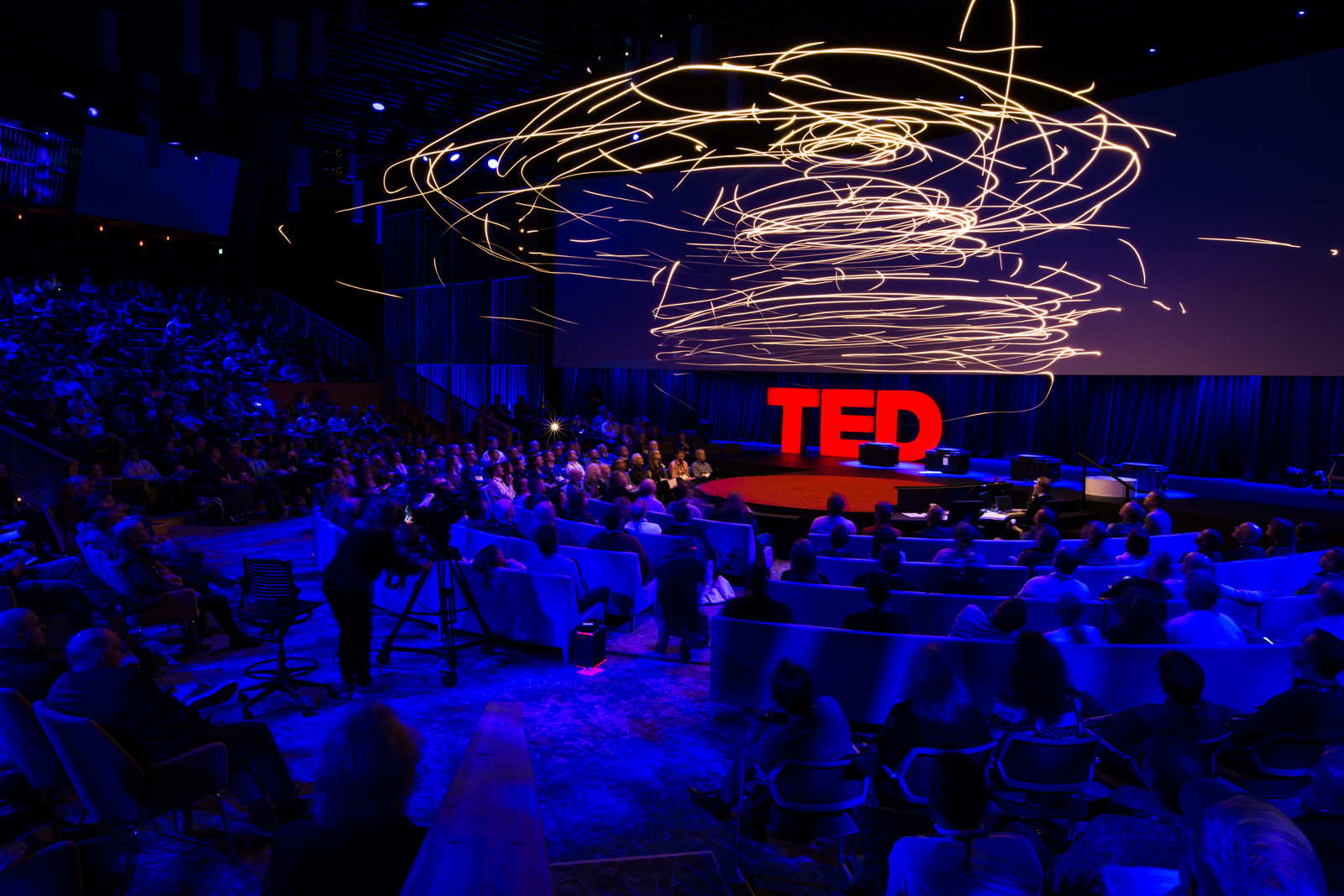

The future of flying machines. Before drones had applications for journalism, inspection, war and environmental monitoring, the mechanics of flying machines were hashed out in research labs. Autonomous systems expert Raffaello D’Andrea develops quadcopters and other flying craft that can reliably coordinate and carry loads, autonomously build tensile structures, and cope with disturbances. And then he unveils his latest projects that are pushing the boundaries of autonomous flight. On stage he demos a flying wing that can hover and recover from disturbance, an eight-propeller craft that’s extremely symmetrical and ambivalent to orientation, and a highly resilient quadcopter that recovers from the loss of even two propellers. To close he dazzles the hushed audience with a swarm of tiny coordinated micro-quadcopters, lit up in a dreamy, swirling array. The effect is like a large group of fireflies, dancing together in unison.

Flying machines demo by Raffaello D’Andrea at TED2016 – Dream, February 15-19, 2016, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman / Ryan Lash / TED

Comments