The stage at TED@IBM bubbles with possibilities … at the SFJAZZ Center, December 6, 2017, San Francisco, California. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

We know that our world — our data, our lives, our countries — are becoming more and more connected. But what should we do with that? In two sessions of TED@IBM, the answer shaped up to be: Dream as big as you can. Speakers took the stage to pitch their ideas for using connected data and new forms of machine intelligence to make material changes in the way we live our lives — and also challenged us to flip the focus back to ourselves, to think about what we still need to learn about being human in order to make better tech. From the stage of TED@IBM’s longtime home at the SFJAZZ Center, executive Ann Rubin welcomes us and introduces our two onstage hosts, TED’s own Bryn Freedman and her cohost Michaela Stribling, a longtime IBMer who’s been a great champion of new ideas. And with that, we begin.

Giving plastic a new sense of value. A garbage truck full of plastic enters the ocean every minute of every hour of every day. Plastic is now in the food chain (and your bloodstream), and scientists think it’s contributing to the fastest rate of extinction ever. But we shouldn’t be thinking about cleaning up all that ocean plastic, suggests plastics alchemist David Katz — we should be working to stop plastic from getting there in the first place. And the place to start is in extremely poor countries — the origin of 80 percent of plastic pollution — where recycling just isn’t a priority. Katz has created The Plastic Bank, a worldwide chain of stores where everything from school tuition and medical insurance to Wi-Fi and high-efficiency stoves is available to be purchased in exchange for plastic garbage. Once collected, the plastic is sorted, shredded and sold to brands like Marks & Spencer and Henkel, who have commissioned the use of “Social Plastic” in their products. “Buy shampoo or detergent that has Social Plastic packaging, and you’re indirectly contributing to the extraction of plastic from ocean-bound waterways and alleviating poverty at the same time,” Katz says. It’s a step towards closing the loop on the circular economy, it’s completely replicable, and it’s gamifying recycling. As Katz puts it: “Be a part of the solution, not the pollution.”

How can we stop plastic from piling up in the oceans? David Katz has one way: He runs an international chain of stores that trade plastic recyclables for money. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

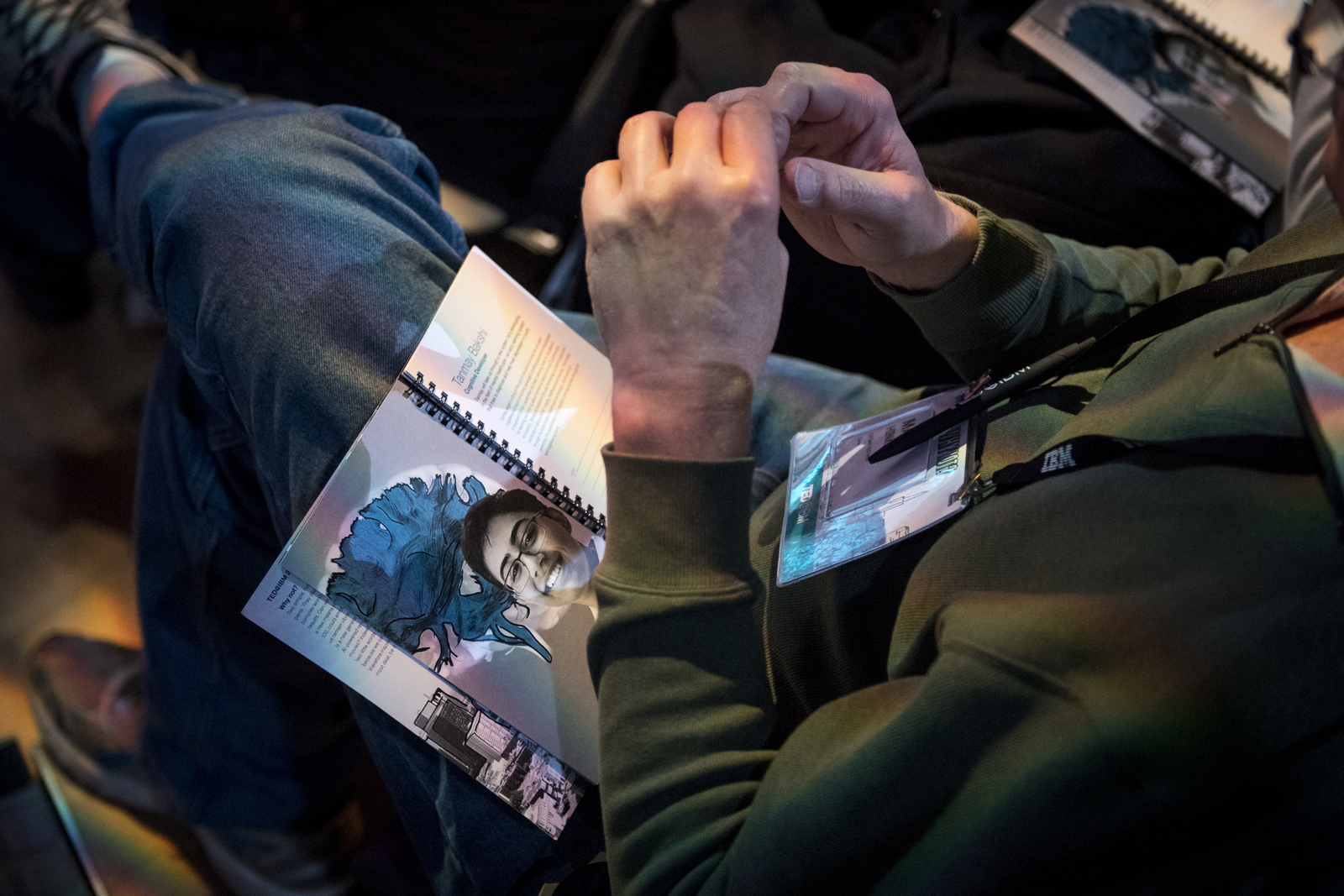

How do we help teens in distress? AI is great at looking for patterns. Could we leverage that skill, asks 14-year-old cognitive developer Tanmay Bakshi, to spot behavior issues lurking under the surface? “Humans aren’t very good at detecting patterns like changes in someone’s sleep, exercise levels, and public interaction,” he says. “If some of the patterns from these suicidal teens go unrecognized and unnoticed by the human eye,” he suggests we could let technology help us out. For the last 3 years, Bakshi and his team have been working with artificial neural networks (ANNs, for short) to develop an app that can pick up on irregularities in a person’s online behavior and build an early warning systems for at-risk teens. With this technology and information access, they foresee a future where a diagnosis is given and all-encompassing help is available right at their fingertips.

An IBMer reads Tanmay Bakshi’s bio — to confirm that, yes, he’s just 14. At TED@IBM, Bakshi made his pitch for a social listening tool that could help identify teens who might be heading for a crisis. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

A better way to manage refugee crises. When the Syrian Civil War broke out, Rana Novack, the daughter of Syrian immigrants, watched her extended family face an impossible choice: stay home and risk their lives, leave for a refugee camp, or apply for a visa, which could take years and has no guarantee. She quickly realized there was no clear plan to handle a refugee crisis of this magnitude (it’s estimated that there are over 5 million Syrian refugees worldwide). “When it comes to refugees, we’re improvising,” she says. Frustrated with her inability to help her family, Novack eventually struck on the idea of applying predictive technology to refugee crises. “I had a vision that if we could predict it, we could enable government agencies and humanitarian aid organizations with the right information ahead of time so it wasn’t such a reactive process,” she says. Novack and her team built a prototype that will be deployed this year with a refugee organization in Denmark and next year with an organization to help prevent human trafficking. “We have to make sure that the people who want to do the right thing, who want to help, have the tools and the information they need to succeed,” she says, “and those who don’t act can no longer hide behind the excuse they didn’t know it was coming.”

After her talk onstage at TED@IBM, Rana Novack continues the conversation on how to use data to help refugees. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

What is information? It seems like a simple question, maybe almost too simple to ask. But Phil Tetlow is here to suggest that answering this question might be the key to understanding the universe itself. In an engaging talk, he walks the audience through the eight steps of understanding exactly what information is. It starts by getting to grips with the sheer complexity of the universe. Our minds use particular tools to organize all this sheer data into relevant information, tools like pattern-matching and simplifying. Our need to organize and connect things, in turn, leads us to create networks. Tetlow offers a short course in network theory, and shows us how, over and over, vast amounts of information tend to connect to one another through a relatively small set of central hubs. We’re familiar with this property: think of airline route maps or even those nifty maps of the internet that show how vast amounts of information ends up flowing through a few large sites, mainly Google and Facebook. Call it the 80/20 rule, where 80% of the interesting stuff arrives via 20% of the network. Nature, it turns out, forms the same kind of 80/20 network patterns all the time — in plant evolution, in chemical networks, in the way a tree branches out from a central trunk. And that’s why, Tetlow suggests, understanding the nature of information, and how it networks together, might give us a clue as to the nature of life, the universe, and why we’re even here at all.

Want to know what information is, exactly? Phil Tetlow does too — because understanding what information is, he suggests, might just help us understand why we exist at all. He speaks at TED@IBM. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

Curiosity + passion = daring innovation. While driving to work in Johannesburg, South Africa, Tapiwa Chiwewe noticed a large cloud of air pollution he hadn’t seen before. While he’s not a pollution expert, he was curious — so he did some research, and discovered that the World Health Organization reported that nearly 14 percent of all deaths worldwide in 2012 were attributable to household and ambient air pollution, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. What could he do with his new knowledge? He’s not a pollution expert — but he is a computer engineer. So he paired up with colleagues from South Africa and China to create an air quality decision support system that lives in the cloud to uncover spatiotemporal trends of air pollution and create a new machine-learning technology to predict future levels of pollution. The tool gives city planners an improved understanding of how to plan infrastructure. His story shows how curiosity and concern for air pollution can lead to collaboration and creative innovation. “Ask yourself this: Why not?” Chiwewe says. “Why not just go ahead and tackle the problem head-on, as best as you can, in your own way?”

Tapiwa Chiwewe helped invent a system that tracks air pollution — blending his expertise as a computer engineer with a field he was not an expert in, air quality monitoring. He speaks at TED@IBM about using one’s particular set of skills to affect issues that matter. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

What if AI was one of us? Well, it is. If you’re human, you’re biased. Sometimes that bias is explicit, other times it’s unconscious, says documentarian Robin Hauser. Bias can be a good thing — it informs and protects from potential danger. But this ingrained survival technique often leads to more harmful than helpful ends. The same goes for our technology, specifically artificial intelligence. It may sound obvious, but these superhuman algorithms are built by, well, humans. AI is not an objective, all-seeing solution; AI is already biased, just like the humans who built it. Thus, their biases — both implicit and completely obvious — influence what data an AI sees, understands and puts out into the world. Hauser walks through well-recorded moments in our recent history where the inherent, implicit bias of AI revealed the worst of society and the humans in it. Remember Tay? All jokes aside, we need to have a conversation about how AI should be governed and ask who is responsible for overseeing the ethical standards of these supercomputers. “We need to figure this out now,” she says. “Because once skewed data gets into deep learning machines, it’s very difficult to take it out.”

A mesmerizing journey into the world of plankton. “Hold your breath,” says inventor Thomas Zimmerman: “This is the world without plankton.” These tiny organisms produce two-thirds of our oxygen, but rising sea surface temperatures caused by climate change are threatening their very existence. This in turn endangers the fish that eat them and the roughly one billion people around the world that depend on those fish for animal protein. “Our carbon footprint is crushing the very creatures that sustain us,” says his thought partner, engineer Simone Bianco, “Why aren’t we doing something about it?” Their theory is that plankton are tiny and it’s really hard to care about something that you can’t see. So, the pair developed a microscope that allow us to enter the world of plankton and appreciate their tremendous diversity. “Yes, our world is based on fossil fuels, but we can adjust our society to run on renewable energy from the sun to create a more sustainable and secure future,” says Zimmerman, “That’s good for the little creatures here, the plankton, and that’s good for us.”

Thomas Zimmerman (in hat) and Simone Bianco share their project to make plankton more visible — and thus easier to care about and protect. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

A poet’s call to protect our planet. “How can something this big be invisible?” asks IN-Q. “The ozone is everywhere, and yet it isn’t visible. Maybe if we saw it, we would see it’s not invincible, and have to take responsibility as individuals.” The world-renowned poet closed out the first session of TED@IBM with his original spoken-word poem “Movie Stars,” which asks us to reckon with climate change and our role in it. With feeling and urgency, IN-Q chronicles the havoc we’ve wreaked on our once-wild earth, from “all the species on the planet that are dying” to “the atmosphere we’ve been frying.” He criticizes capitalism that uses “nature as its example and excuse for competition,” the politicians who allow it, and the citizens too cynical to believe in facts. He finishes the poem with a call to action to anyone listening to take ownership of our home turf, our oceans, our forests, our mountains, our skies. “One little dot is all that we’ve got,” says IN-Q. “We just forgot that none of it’s ours; we just forgot that all of it’s ours.”

With guitar, drums and (expert) whistling, The Ferocious Few open Session 2 with a rocking, stripped-down performance of “Crying Shame.” The band’s musical journey from the streets of San Francisco to the big cities of the United States falls within this year’s TED@IBM theme, “Why not?” — encouraging musicians and others alike to question boundaries, explore limits and carry on.

Why the tech world needs more humanities majors. A few years ago, Eric Berridge’s software consultancy was in crisis, struggling to deal with a technical challenge facing his biggest client. When none of his engineers could solve the problem, they went to drown their sorrows and talk to their favorite bartender, Jeff — who said, “Let me talk to these guys.” To everyone’s surprise and delight, Jeff’s meeting the next day shifted the conversation completely, salvaged the company’s relationship with its client, and forever changed how Berridge thinks about who should work in the tech sector. At TED@IBM, he explained why tech companies should look beyond STEM graduates for new hires, and how people with backgrounds in the arts and humanities can bring creativity and unique insight into a technical workplace. Today, Berridge’s consulting company boasts 1,000 employees, only 100 of whom have degrees in computer programming. And his CTO? He’s a former English major/bike messenger.

Eric Berridge put his favorite bartender in a room with his biggest client — and walked out convinced that the tech sector needs to make room for humanities majors and people with multiple kinds of skills, not just more and more engineers. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

The surprising and empowering truth about your emotions. “It may feel to you like your emotions are hardwired, that they just happen to you, but they don’t. You might believe your brain is pre-wired with emotion circuits, but it’s not,” says Lisa Feldman Barrett, a psychology professor at Northeastern University who has studied emotions for 25 years. So what are emotions? They’re guesses based on past experiences that our brain generates in the moment to help us make sense of the world quickly, Barrett says. “Emotions that seem to happen to you are actually made by you,” she adds. For example, many of us hear our morning alarm go off, and as we wake up, we find ourselves enveloped by dread. We start thinking about all of our to-dos — the emails and calls to return, the drop-offs, the meals to cook. Our mind races, and we tell ourselves “I feel anxious” or “I feel overwhelmed.” This mind-racing is prediction, says Barrett. “Your brain is searching to find an explanation for those sensations in your body that you’re experiencing as wretchedness. But those sensations may have a physical cause.” In other words — you just woke up, maybe you’re just hungry. The next time you feel distressed, ask yourself: “Could this have a purely physical cause? Am I just tired, hungry, hot or dehydrated?” And we should be empowered by these findings, declares Barrett. “The actions and experiences that you make today become your brain’s predictions for tomorrow.”

In a mind-shifting talk, Lisa Feldman Barrett shares her research on what emotions are … and it’s probably not what you think., Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

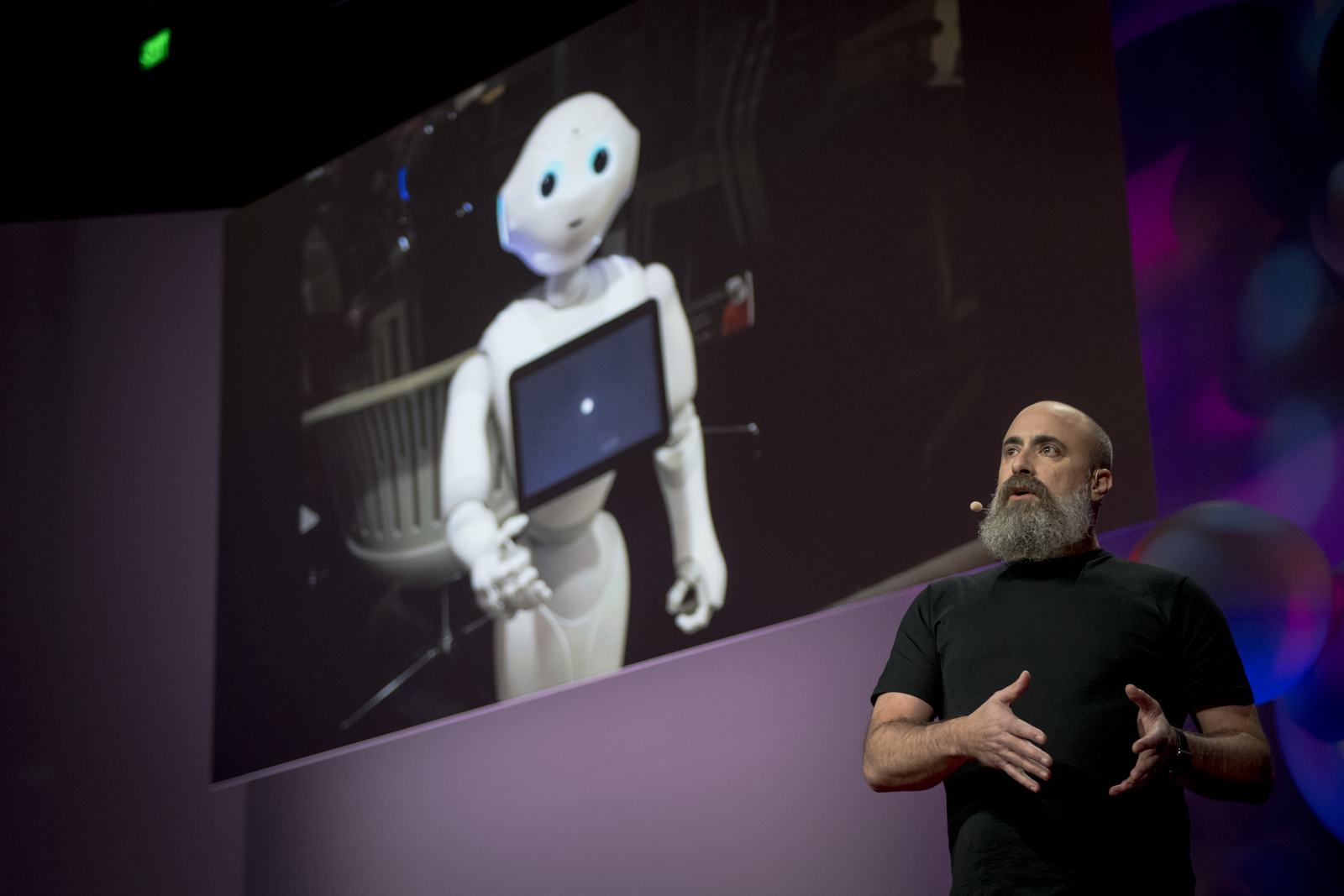

Emotionally authentic relationships between AI and humans. “Imagine an AI that can know or predict what you want or need based on a sliver of information, the tone of your voice, or a particular phrase,” says IBM distinguished designer Adam Cutler. “Like when you were growing up and you’d ask your mom to make you a grilled cheese just the way you like it, and she knew exactly what you meant.” Cutler is working to create a bot that would be capable of participating in this kind of exchange with a person. More specifically, he is focusing on how to form an inside joke between machine and mortal. How? “Interpreting human intent through natural language understanding and pairing it with tone and semantic analysis in real time,” he says. Cutler contends that we humans already form relationships with machines — we name our cars, we refer to our laptops as being “cranky” or “difficult” — so we should do this with intention. Let’s design AI that responds and serves us in ways that are truly helpful and meaningful.

Adam Cutler talks about the first time he encountered an AI-enabled robot — and what it made him realize about his and our relationship to AI. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

Can art help make AI more human? “We’re trying to create technology that you’ll want to interact with in the far future,” says artist Raphael Arar. “We’re taking a moonshot that we’ll want to be interacting with computers in deeply emotional ways.” In order for that future of AI to be a reality, Arar believes that technology will have to become a lot more human, and that art can help by translating the complexity of what it means to be human to machines. As a researcher and designer with IBM Research, Arar has designed artworks that help AI explore nostalgia, conversations and human intuition. “Our lives revolve around our devices, smart appliances, and more, and I don’t think this will let up anytime soon,” he says, “So I’m trying to embed more ‘humanness’ from the start, and I have a hunch that bringing art into an AI research process is a way to do just that.”

How can we make AI more human-friendly? Raphael Arar suggests we start with making art. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

Where the body meets the mind. For millennia, philosophers have pondered the question of whether the mind and body exist as a duality or as part of a continuum, and it’s never been more practically relevant than it is today, as we learn more about the way the two connect. What can science teach us about this problem? Natalie Gunn studies both Alzheimer’s and colorectal cancer, and she wants to apply modern medicine and analytics to the mind-body problem. For her work on Alzheimer’s, she’s developing a blood test to screen for the disease, hoping to replace expensive PET scans and painful lumbar punctures. Her research on cancer is where the mind-body connection gets interesting: Does our mindset have an impact on cancer? There’s little conclusive evidence either way, Gunn says, but it’s time we took the question seriously, and put the wealth of analytical tools we have at our disposal to the test. “We need to investigate how a disease of the body could be impacted by our mind, particularly for a disease like cancer that is so steeped in our psyche,” Gunn says. “When we can do this, the philosophical question of where the body ends and the mind begins enters into the realm of scientific discovery rather than science fiction.”

Researcher Natalie Gunn wants to suggest a science-based lens to look at the mind-body problem. Photo: Russell Edwards / TED

Is Parkinson’s an electrical problem? Brain researcher Eleftheria Pissadaki studies Parkinson’s, but instead of focusing on the biological aspects of the disease, like genetics and dopamine depletion, she’s looking at the problem in terms of energy. Pissadaki and her team have created mathematical models of dopamine neurons, the neurons that selectively die in Parkinson’s, and they’ve found that the bigger a neuron is, the more vulnerable it becomes … simply because it needs a lot of energy. What can we do with this information? Pissadaki suggests we might someday be able to neuroprotect our brain cells by “finding the fuse box for each neuron” and figuring out how much energy it needs. Then we might be able to develop medicine tailored for people’s brain energy profiles, or drugs that turn neurons off whenever they’re getting tired but before they die. “It’s an amazingly complex problem,” Pissadaki says, “but one that is totally worth pursuing.”

Eleftheria Pissadaki is imagining new ways to think about and treat diseases like Parkinson’s, suggesting research directions that might create new hope. Photo: Photographer Russell Edwards / TED

How to build a smarter brain. Just as we can reshape our bodies and build stronger muscles with exercise, Bruno Michel thinks we can train our way to better, faster brains — brains smart enough to compete with sophisticated AI. At TED@IBM, the brain fitness advocate discussed various strategies for improving your noggin. For instance, to think in a more structured way, try studying Latin, math or music. For a boost to your general intelligence, try yoga, read, make new friends, and do new things. Or, try pursuing a specific task with transferable skills as Michel has done for 30 years. He closed his talk with the practice he credits with significantly improving both the speed of his thinking and his reaction times— tap dancing!

- Bruno Michel speaks at TED@IBM at SFJAZZ Center, December 6, 2017, San Francisco, California. Photo: Photographer Russell Edwards / TED

- Bruno Michel speaks at TED@IBM at SFJAZZ Center, December 6, 2017, San Francisco, California. Photo: Photographer Russell Edwards / TED

- Bruno Michel speaks at TED@IBM at SFJAZZ Center, December 6, 2017, San Francisco, California. Photo: Photographer Russell Edwards / TED

- Bruno Michel speaks at TED@IBM at SFJAZZ Center, December 6, 2017, San Francisco, California. Photo: Photographer Russell Edwards / TED